Two positive development stories emerged from the UK education sector last week.

1. A new tutoring scheme is hiring Sri Lankan tutors for British children.

The UK has launched a new government-funded tutoring scheme to help children catch up after COVID-19. Last Friday, the Guardian drew attention to the fact that one company involved in the scheme is using tutors in Sri Lanka, some of whom are under 18 and earning the equivalent of just £1.57 per hour. Those under-18s are 17-year-olds who are studying for an undergraduate degree, and make up 0.3 percent of the tutor workforce. The (minimum) hourly earnings on the scheme are 425 Sri Lankan rupees. Is this exploitation?

Whilst £1.57 per hour might sound derisory to a British audience, 425 rupees may not be such a bad wage in Sri Lanka. First, “Purchasing Power Parity” conversions matter. Prices are cheaper in Sri Lanka, so money goes further. The conversion factor between Sri Lanka and the UK is around 0.35, so whilst 425 rupees can only buy £1.57 at market exchange rates, it can actually buy the equivalent of around £4.49 worth of goods in Sri Lanka.

Second, 425 rupees is well above average earnings for university graduates. Median hourly earnings of all urban adults (aged 15-64) with a degree in Sri Lanka were 184 rupees, according to the most recent data I have at hand (the 2012 World Bank STEP Survey). Adjusted for GDP growth and inflation of about 87 percent, that is 344 rupees in 2021 money—less than the wage of the “exploitative” tutoring scheme.

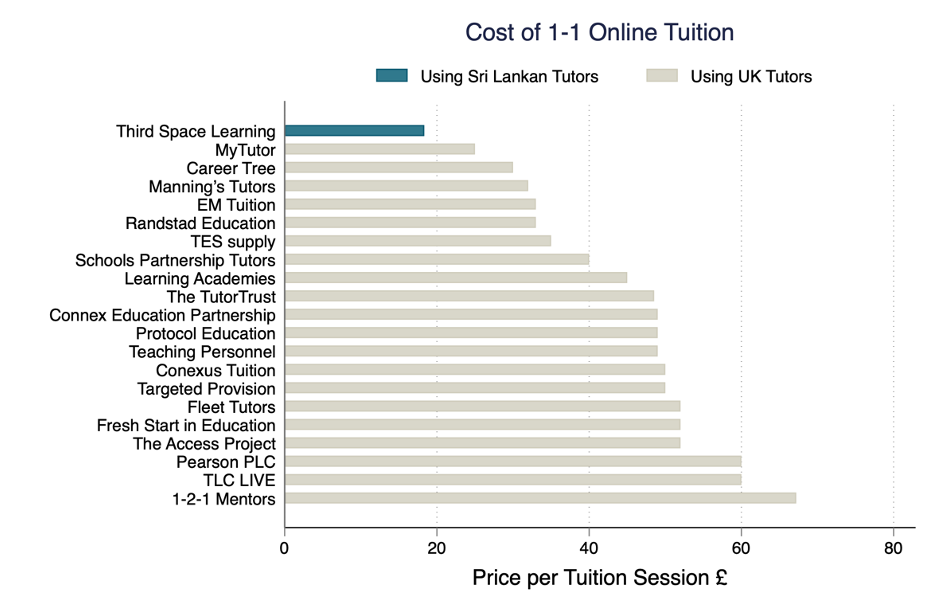

Is offshoring a good deal for the British taxpayer? The National Tutoring Programme lists 33 approved providers that schools can choose from. Of these, 21 list a price for 1-1 online tutoring. The average cost of the 20 providers using British tutors is £45.50 per session (excluding VAT). The cost for the one provider using Sri Lankan tutors is £18.33—less than half the price. Of this, just over half (52 percent) goes to the London office for curriculum and technology design and management, 29 percent for tutor training in Sri Lanka, and 17 percent to the tutor, leaving 2 percent profit.

Figure: Online tutoring by Sri Lankan tutors costs a fraction of tutoring by UK tutors

Note: Data from the National Tutoring Programme “Guide to approved tuition partners 2020–21”

The overall value of international tuition clearly rests not just on price but also on the effectiveness of the tuition. This should be independently tested with a well-powered evaluation. But a 60 percent cost reduction is a great starting point for any cost-effectiveness calculation.

£1.57 per hour doesn’t sound like much, and it isn’t. But the sad reality is that wages are simply very, very low in Sri Lanka, as they are in most countries around the world. Figuring out new ways for people in rich countries to buy services from people in poor countries might be one of the best things anyone can do for development.

2. The UK Department for Education is proposing a new international teaching qualification, which could make international recruitment easier.

Certain roles in UK schools have been consistently undersupplied by the UK market, and international recruitment of teachers will need to be ramped up to fill the gaps. For example the number of new teacher trainees in secondary school maths in England was only 64 percent of the target level in 2019-20. The Migration Advisory Committee currently lists secondary school teachers in maths, science, and foreign languages as a shortage occupation.

The new International Qualified Teacher Status (iQTS) would allow accredited training providers to sell their training certificate internationally, with the expectation that British international schools would be an important market. But the concept also leaves open the door to a smoothed transition to Qualified Teacher Status in England—a requirement for many teacher jobs.

At present only 7 percent of teaching and education professionals in the UK are non-British nationals. This compares with 13 percent of health professionals. Part of the reason for the difference is the weak comparability of qualifications. At present, teachers from European and rich English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the US) have their qualifications automatically recognised. A new qualification could provide a route for teachers in Kenya, for example, to study for and attain an accredited qualification in their home countries that would be easily recognised and allow them to apply for teaching jobs in the UK.

The starting salary for qualified teachers in England is £25,714 per year (more in London). Starting salaries in Kenya are Ksh 25,692 per month, or around £4,046 per year (after adjusting for purchasing power). So a new graduate moving from Kenya to the UK could increase their salary by over 500 percent, while filling a much-needed gap in the UK’s teacher labor market.

Don’t mention the “brain drain” fallacy

Would making it easier for teachers to leave Kenya be bad for Kenyan education? Concerns about “brain drain” are still depressingly common despite decades of debunking from researchers (not least my CGD colleague Michael Clemens). They are based on a fallacy that the stock of skills in a country is fixed. But the opposite is usually true. Investment in skills is constrained by a lack of jobs. A new route to higher wages in the UK could increase the number of Kenyans training to be teachers, if there was a realistic chance they could increase their earnings 500 percent. As an example, there are thousands of Filipino nurses in the United States. But for every nurse who migrated, 10 were licenced, leaving more nurses in the Philippines—not fewer. Similarly the migration of Indian IT workers to the United States led to a brain gain in India with more new students training in IT than migrated.

And if the UK is still concerned about the impact on poor countries of attracting their teachers, it could set up global skills partnerships, agreeing to reimburse countries for publicly funded teacher training through the UK aid budget.

What these two policies have in common

There is a chasm in earnings across countries. Migration and trade (in this case in tuition services) are two of the key ways to raise the earnings of people in poor countries and promote development. If “Global Britain” is to be a “force for good in the world”, it could do worse than experiment further with (and evaluate!) these potential win-win solutions.

You can respond to the government consultation on introducing International Qualified Teacher Status (iQTS) until 3 May 2021 here. Thanks to Susannah Hares and Helen Dempster for comments on a draft of this blog.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.