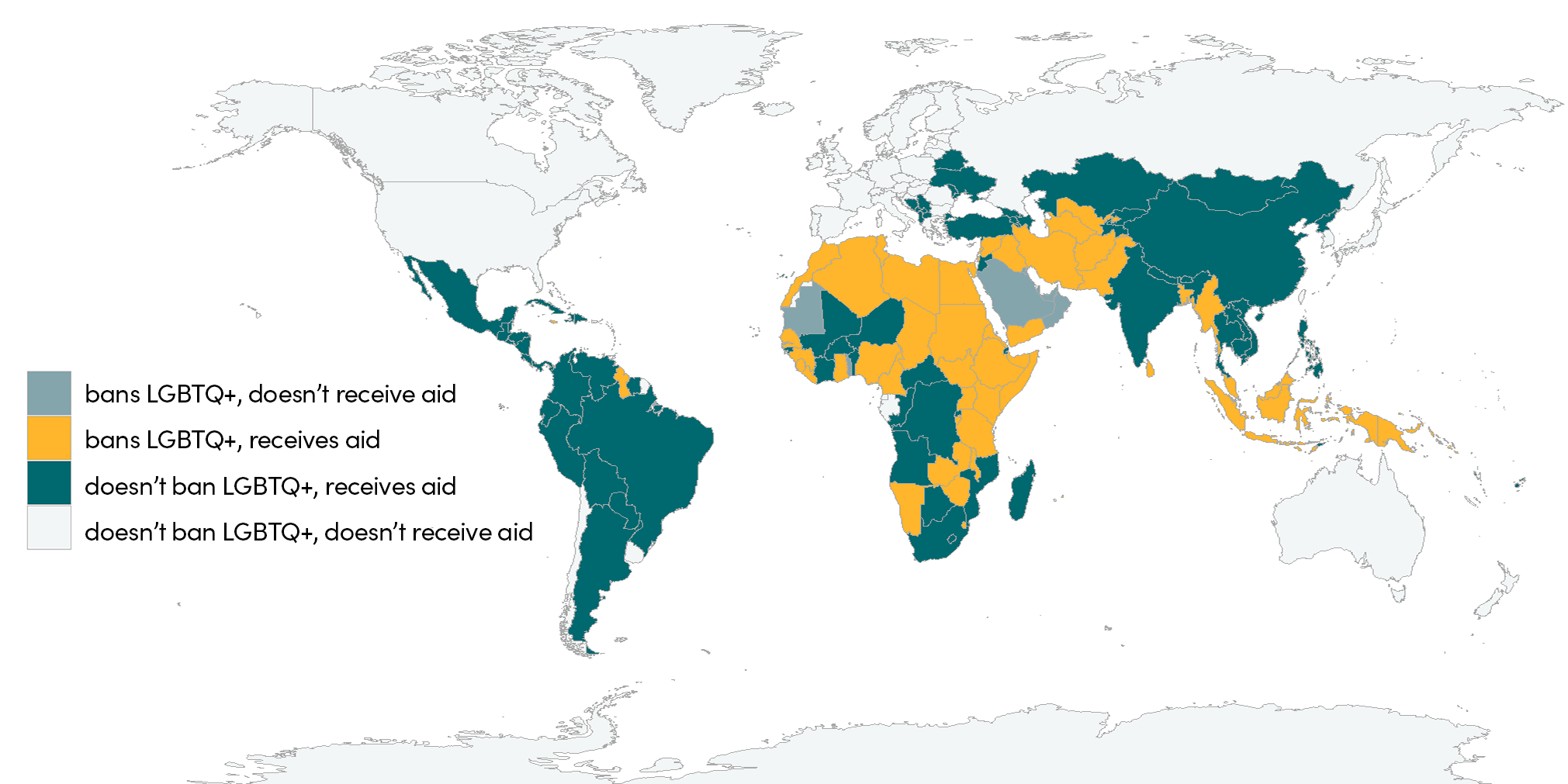

In around 70 countries it is still illegal—and in many cases punishable by death or imprisonment—to love who you want to. Half of these countries are in Africa and more than half are Commonwealth countries. Many are significant recipients of UK aid. The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) explicitly aims to bring “the global reach of its diplomatic network and the power of its development expertise together to promote the UK’s…values internationally.” And yet—even though laws criminalising homosexuality often originate from British colonial rule—promoting rights for LGBTQ+ people ranks very low on UK aid priorities.

Figure 1. Countries that criminalise LGBTQ+ people, by whether they received aid from UK in 2020

Source CGD analysis from https://www.humandignitytrust.org/LGBTQ+-the-law/map-of-criminalisation/ and CRS data

As many people across the world celebrate the LGBTQ+ community during this month of Pride, we discuss how and why the UK should better promote and protect the rights of LGBTQ+ communities in developing countries through its aid programme.

UK Aid support for LGBTQ+ rights is dismally low

Of the £10 billion disbursed in bilateral aid in 2020 by the UK, projects worth just £2 million (around 0.02 percent) mentioned the acronym LGBTQ+ in the project description, although the former Foreign Secretary cites £5.47million (around 0.05 percent) as the spending in 2020. Of over two thousand aid project business cases published on Devtracker, only 29 mention “LGBTQ+”, and many of these only mentioned the phrase in passing.

It’s clear that addressing LGBTQ+ rights is a low priority for UK aid. Is this because the UK isn’t interested, or because aid is not an appropriate tool for this? We argue here that supporting LGBTQ+ rights can be a good use of aid money.

There are at least three potential ways in which more aid could be used to focus on LGBTQ+ issues:

1. Changing social norms and legislation

One way that donors can use aid to promote LGBTQ+ causes is to fund efforts to bring about change in norms or laws. Social movements and civil society organisations advocate for greater legal rights, often at great personal risk. Funding such groups could be a good use of aid money. Indeed this kind of spending appears to constitute the majority of the £5.47 million figure quoted by the former foreign secretary. Around half was allocated to the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, and another £0.5 million to the Human Dignity Trust. Both challenge laws that discriminate against people of different sexualities or genders.

How effective might such spending be?

Although the evidence is limited, some illustrative figures on costs and benefits are striking. Take one example; the Human Dignity Trust, an organisation who “use the law to defend the human rights of LGBTQ+ people globally”. Over the past decade they have spent less than £7 million in total. Their most credible direct claims of impact are Belize, where the Trust was responsible for some of the key successful legal arguments that led to decriminalisation of same sex relationships, and Northern Cyprus, where the Trust filed the court case that directly prompted the legislature to repeal the offending law. A conservative estimate of just some of the costs of discrimination against LGBTQ+ people (related to health and wages) sum to around 1 percent of GDP per year. Applied to the economies of Belize and Northern Cyprus, this amounts to around $60 million.

What effect would changing the law have on discrimination? Estimates suggest that a change in the law reduces the share of people who think that their society is a “bad place” for homosexuals by around 9 percent. If we took this to be a 9 percent reduction in the amount of discrimination, we arrive at a dollar benefit of around $5 million (£4 million). Even if this was all the Human Dignity Trust had achieved in its ten years (changing the law in Belize and Northern Cyprus), that success alone could produce an annual return on investment of 62 percent. Now that’s a smart buy, even focusing very narrowly on the economic case and leaving aside the more fundamental issue of basic dignity and human rights, as well as other legal topics in addition to decriminalisation that the Trust has successfully advanced.

One concern is whether existing organisations could usefully increase their spending at the margin in the short term (in other words, is there actually room for more funding?). The Human Dignity Trust has supported reform efforts in 25 countries and secured successful judgments involving six countries (a hit rate of 24 percent). This suggests that Belize and Northern Cyprus were not one-offs and that similar efforts have a reasonable likelihood of success. And with nearly 70 countries in which homosexuality is illegal, there is still a long way to go.

But could efforts backfire?

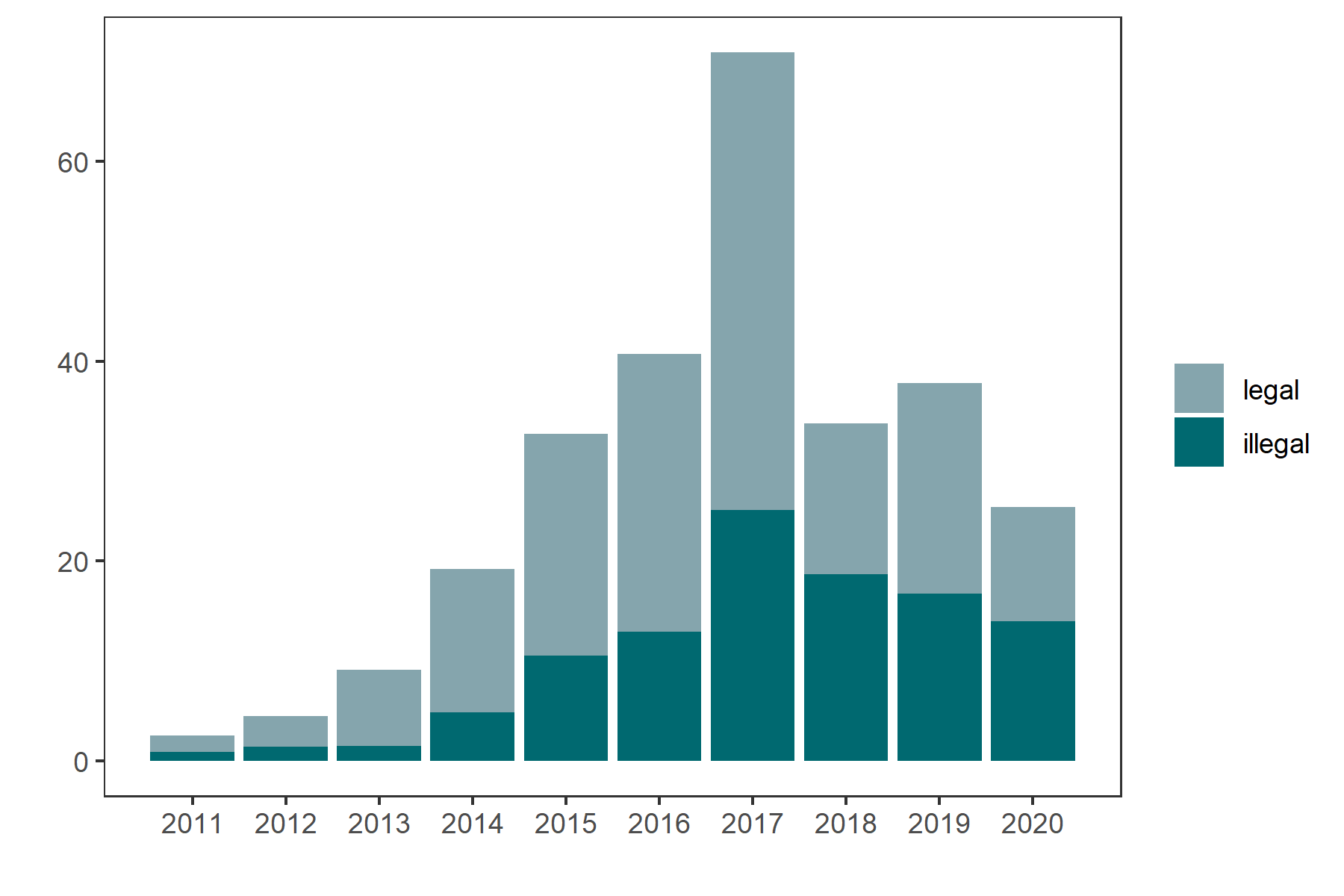

Some argue that international support for LGBTQ+ rights could be perceived as cultural imperialism and result in even more regressive laws. For example, a former Minister of Information in Ghana advised Western donors to “let us do our own evolving at our own rate”. We find this argument lacking, and an excuse for inaction. Similar arguments about cultural imperialism could be made about human rights more generally, and yet western donors work hard and invest substantial portions of their aid budgets to promote gender equality in developing countries, with no qualms about using their money and influence to change legislation and social norms. And this aid can work—increasing gender equality and access to basic services for women and girls. Much of the FCDO funding for human rights is spent in countries where homosexuality is illegal (figure 2)—in some cases punishable by death. And yet project business cases don’t even mention the flagrant abuse of human rights of the LGBTQ+ community.

Figure 2. While much FCDO funding for human rights is channelled to countries where homosexuality is illegal, very few projects even mention the egregious human rights abuses of LGBTQ+ people

Bilateral ODA spent on human rights, by whether homosexuality illegal in recipient country

2. Helping LGBTQ+ people access basic services and opportunities

Whether or not it is legal, LGBTQ+ people face barriers to services or opportunities. This includes denial of health services to people who identify as a different gender to their birth sex, discrimination in the labour market, or lower access to education or social services. Each barrier means that LGBTQ+ people have fewer opportunities to make a living and suffer worse health and education outcomes. All else equal, aid is more effective when targeted at the most vulnerable people, so it makes sense to put a positive weight on LGBTQ+ communities in allocation decisions.

How would this look in practice? It may not be easy for outsiders to identify the right way to channel aid. But again, there are local organisations who aim to address this exact issue, filling gaps in services for LGBTQ+ that are left by systematic discrimination. The business case for one FCDO project specifically mentions the importance of using Civil Society Organisations to reach marginalised groups. Providing funding for these organisations might be a way to target these particularly disadvantaged communities, true to the spirit of “leave no one behind”. The UK must also ensure that aid money is not funding damaging and insulting “conversion therapy”.

3. “Mainstreaming”—integrating LGBTQ+ rights into other FCDO programmes

An alternative—not mutually exclusive with the above—is to try and design all programmes so that where possible, they can further the rights and opportunities of LGBTQ+ people. There have been efforts to “mainstream” several other issues, notably gender and climate.

One simple way to do this would be to include in the template for new project business cases a question about whether the proposed intervention will have a positive impact on LGBTQ+ communities. Of course, not all aid programmes can, but a question like this would mandate staff to assess the opportunity. The €155 million Facility for Refugees in Turkey (FRIT) is a good example of how this might work. In the business case, the FCDO rightly promotes the UK’s advocacy for the most vulnerable (including LGBTQ+ people) on the FRIT steering committee.

Another approach could be to add markers to projects in different sectors that have some focus on LGBTQ+ issues, in order to track spending. But such markers are prone to gaming, and donors’ use of both gender and climate markers have come under fire (some projects marked as having a principal climate mitigation focus, for example, do not actually mention climate in the project documents). Markers then, are not a substitute for concerted effort to take into account LGBTQ+ issues more broadly. The low prominence of LGBTQ+ mentions in FCDO project documents suggests that more effort could be made to think about which projects could have a positive impact on LGBTQ+ rights.

Beyond aid: first, do no harm

Aid is not the only (and perhaps not the best) lever that the UK has to promote the rights and wellbeing of the LGBTQ+ community. Of the top 10 refugee-hosting countries, homosexuality is illegal in eight, suggesting that expanding refugee resettlement is likely to remove many LGBTQ+ people from dangerous situations. Reforming the Home Office to be more sensitive to the issue and stop asking intrusive questions in asylum interviews would be a useful step. The Home Office should also commit to not sending LGBTQ+ people to a regime that will persecute them.

If the UK is serious about promoting British values and human rights, it should give more prominence to the rights of the LGBTQ+ community in its aid programme.

Our analysis of FCDO project documents show UK aid could be used far more expansively to improve the lives of the LGBTQ+ community in developing countries, where LGBTQ+ people are systemically exposed to inhumane laws and treatment. In countries that are among the largest recipients of UK aid—including Nigeria—same-sex relationships are punishable with death by stoning. This is an outrage and it’s long past time for the UK to consider what more it can do to promote LGBTQ+ equality worldwide.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.