Recommended

Key recommendations

Promote mutually beneficial Northern Triangle migration through two phases of action.

In the short term, improve access to H-2 visa programs under current law by connecting US employers to employees in the region. To do so:

- Establish a Bilateral Labor Markets Special Coordinator’s Office

- Negotiate mutually beneficial bilateral labor agreements

- Develop an outreach strategy for legal migration pathways

In the long term, introduce new bilateral agreements based on the Global Skill Partnership model to facilitate economic recovery post COVID-19.

In the past decade, migration to the United States from Central America’s Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) has increased substantially. The number of people living in the United States (US) who were born in the region increased by 78 percent from 2010 to 2019.[1] In recent years, families and unaccompanied children seeking asylum have made up a progressively larger share of the individuals seeking entrance at the southern border.[2] Poverty and extreme violence—significant drivers of migration from the region—have been exacerbated by COVID-19. As a result, the US should expect an increase in migration from the region in the near future, if one has not already begun.[3]

2019 saw the highest level of apprehensions at the southern border in 12 years, and people from the Northern Triangle accounted for over 80 percent of those apprehended.[4] The Trump administration responded with the Migrant Protection Protocols, also known as “Remain in Mexico,” allowing the Department of Homeland Security to return non-Mexican asylum seekers attempting to cross the US southern border to Mexico to await their hearing.[5]

With limited access to legal migration pathways, some Northern Triangle migrants enter the US through irregular channels and find work in the black market. This dynamic hinders job creation and undermines border security. The US should invest in expanding legal pathways for large-scale, employment-based migration, helping to meet US labor market demands.

In the short-term, the Biden administration should improve access to existing legal migration pathways to Northern Triangle applicants. Pathways such as the H-2A and H-2B visa programs allow US employers to bring migrants to the US to fill seasonal agricultural (H-2A) and nonagricultural (H-2B) jobs. With additional funding, such pathways could properly benefit sectors in need of additional labor,[6] including caregiving, agriculture, and tourism, to complement the existing workforce expansion under the Biden Plan for Mobilizing American Talent.[7] In the longer term, the Biden administration should introduce new bilateral agreements with the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras based on the Global Skill Partnership model to facilitate economic recovery post COVID-19.[8]

How migration benefits the US economy

Many sectors of the US economy depend on low-paid migrant labor, including agriculture,[9] tourism,[10] and healthcare.[11] The migration of low-paid workers to the US remains a contentious political issue. Yet evidence suggests that fears of migrants adversely impacting the wages, employment, and living standards of native low-paid workers are largely misplaced, while migrants’ positive effects on the broad economy are significant and typically underestimated.[12] Each H-2 worker in the US adds more than $20,000 per year to the revenues of their employer,[13] thus directly and indirectly generating positive US tax revenue.[14] For example, an economic analysis of the North Carolina farm industry revealed that 7,000 foreign farm workers added somewhere between $248 million and $381 million to the state’s economy in a single year—creating one additional American job for every three to five seasonal foreign farm workers.[15]

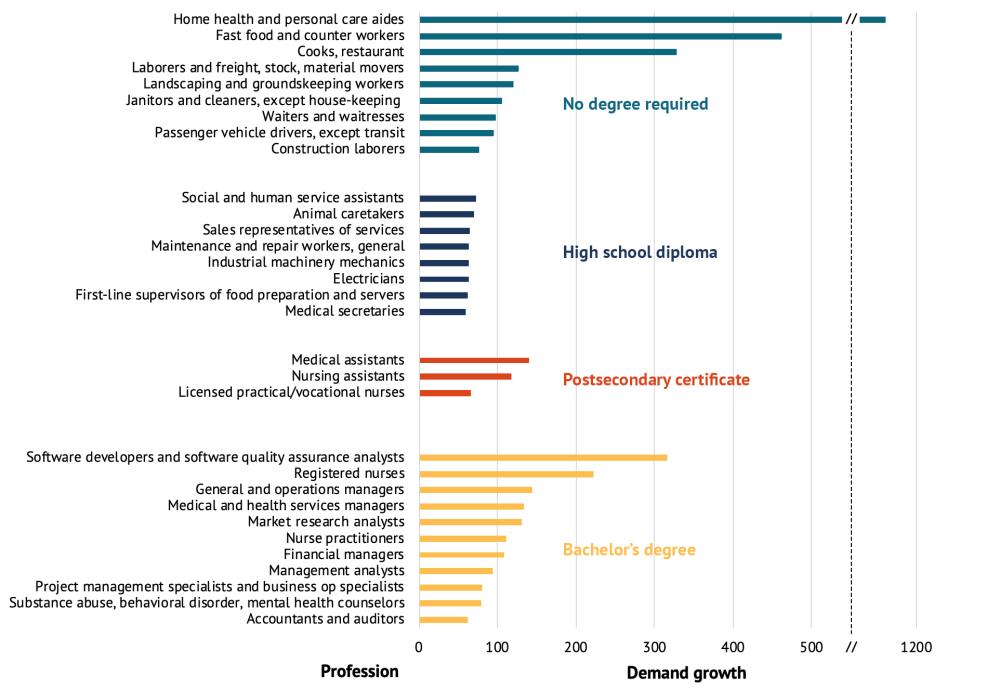

Furthermore, the US economy faces shortages of workers in a number of industries that endure during the current COVID-19 pandemic, holding back American businesses and harming American consumers (figure 1). Over the next 10 years, even despite the adverse economic effects of COVID-19, the total number of net new jobs of any kind will be 6 million.[16] And while some industries will shrink, jobs that don’t require more than a high school education will account for roughly a third of all new net growth in employment. In addition to a greater focus on local skill-building and mobilizing underemployed talent, US policymakers should think creatively about migration interventions that meet the needs of the US economy at all skill levels, as well as those of poorer economies around the world.

Figure 1. Rising demand for low-paid workers: The 30 occupations with largest projected absolute growth in US labor demand, 2019-2029, in thousands of new jobs

Note: Home health and personal care aides now combined into one OES code (31-1120). Demand growth is the change in absolute number of jobs (thousands) projected between 2019-2029. Education requirement is “typical formal education credential at entry level” as assessed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics

The connection between migration and economic prosperity in the Northern Triangle

President-Elect Biden’s plans for a “four-year, $4 billion regional strategy to address factors driving migration from Central America” acknowledges the lack of security and prosperity that pushes migrants to make the journey to the US.[17] This focus on improving economic development and opportunities in Central America is correct, though it is unlikely to deter irregular migration (at least in the short term).

On the whole, emigration rises with development, up to a point. Within low-income countries, richer people are more likely to emigrate.[18] And as low-income countries economically grow, more people are more likely to emigrate.[19] Investing in targeted aid programs may have some impact on specific root causes (e.g., violence reduction programs) but general economic development only deters emigration if successful in the long term.

To channel this movement into more productive pathways, the Biden administration should invest in both increasing the number of employment-based visas available to people from the Northern Triangle, and ensuring efficient and humane border enforcement. Solely providing evidence as to the dangers of irregular migration is unlikely to deter would-be migrants. Evidence from Mexico shows that only by investing in both legal labor pathways and border enforcement can the US reduce pressure to migrate via irregular channels.[20] This can be done effectively through cooperation with Northern Triangle countries and smart program design.

Such investments have the greatest potential to increase economic development in the Northern Triangle, and therefore curb irregular migration rates in the long term. Migrant workers can access higher earnings abroad and send back remittances, making such pathways “among the most effective development policies evaluated to date.”[21]

In the short term, improve access to the H-2 visa programs

The Biden administration can and should improve access to the H-2 visa program under current law.[22] Because US seasonal and temporary work visas are employer-led, improving access to them will require the administration to actively facilitate relationships between US employers, US government agencies, and Northern Triangle governments. This kind of cooperation is feasible: Canada has done this in partnership with Guatemala for the last 16 years and with Mexico dating back to 1974.[23]

Although the Trump administration signed bilateral agreements with Guatemala[24] and El Salvador[25] purportedly intended to facilitate increased “transparency, accountability, and worker safety” in the H-2A program, these agreements provided no actionable steps or accountability measures to ensure improved conditions for and recruitment of temporary migrants.

Still, bilateral agreements with the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras could be used to facilitate access to the H-2A and H-2B visa programs by Northern Triangle migrants. As a starting point, the Biden administration should establish a Bilateral Labor Markets Special Coordinator’s Office within the Department of Labor.

Establish a Bilateral Labor Markets Special Coordinator’s Office

At present, there is no office, bureau, or agency responsible for creating policy, designing projects, or executing programs related to migration and development. This lack of internal coordination has undermined bilateral cooperation. For example, the H-2 visas were created and are managed with essentially no internal or bilateral cooperation. This unilateral approach reduces the ability of the country of origin to provide oversight of working conditions and recruitment.

A Bilateral Labor Markets Special Coordinator’s Office would create an internal hub for negotiating bilateral labor agreements with the respective ministries in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. This hub would coordinate between various US government agencies to establish coherence between domestic and international policy priorities, track and collect information on workers, and conduct in-depth evaluations to ensure programs are designed effectively.

Negotiate mutually beneficial bilateral labor agreements

This Special Coordinator’s Office would then work with Northern Triangle governments to sign bilateral labor agreements, thereby improving access to the H-2 visa programs for would-be migrants. A CGD working group—Shared Border, Shared Future: A Blueprint for Regulating US-Mexico Labor Mobility—set out a framework for what a bilateral worker agreement could look like between the US and Mexico. Its vision and practical policy levers should be applied similarly to bilateral worker agreements between the US and the three Northern Triangle countries. Such bilateral agreements can be effective, if implemented with elements such as:[26]

- Certified interlocutors who can provide notice of job opportunities, pre-select candidates, and coordinate with employers on facilitating recruitment. These interlocutors could be international organizations such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), ethical recruitment companies, or a specified government agency. Such an approach ensures that US laws (e.g., which ban illegal fees that unregulated recruiters commonly charge to migrants) are enforced.

- Pre-departure training, including information about the culture of the destination market, employment contracts and what to do if they are violated, health and safety, financial literacy, and where to go to seek support abroad.

- Sectoral portability, meaning beneficiaries would be able to move between employers within a certain segment of the labor market (either a sector, or a geographical area, or both). Currently, H-2 visa beneficiaries are tied to their employer, which can lead to abuse and exploitation. Such a system is also inflexible to the US labor market and associated skill shortages. There could be limited exceptions for certain jobs, but sectoral portability should be the norm.

- Appropriate validity periods given that seasonal workers do return home when visa programs are well-designed. US law requires all H-2 nonimmigrant visa applicants to satisfy officials at the US embassy that he or she has strong ties to their home country and intends to return—a burden met by the large majority of H-2 applicants. What deters such return is the fear that seasonal workers might lose the opportunity to once again work in the US.

Bilateral labor agreements could also include elements such as:

- Minimum employment guarantees for repeat participants with a track record of complying with their visa requirements.

- Targeting of employers in remote areas to ensure skill shortages in all areas are met.

Such policy levers will be successful in fostering cooperation internally to ensure evaluation of labor market impact and externally to advance regional partnerships with the Northern Triangle and Mexico. Improved conditions for migrants themselves, as granted by bilateral labor agreements, will be most successful if widely available.

Develop an outreach strategy for legal migration pathways

The number of US seasonal work visas approved for Northern Triangle migrants has been low and stagnant in recent years.[27] One of the reasons for this low take-up is a low level of awareness among would-be migrants as to the opportunities available.

For a migrant deciding between the two, greater accessibility to H-2 visa programs would appear competitive compared to an unlawful pathway. Employers petitioning for a visa are restricted from passing any of the application, recruitment, or travel costs onto the beneficiary, so an applicant for an H-2A visa pays nothing. This is compared to the average fees associated with irregular migration, which are routinely increasing.[28]

A proactive outreach strategy, led by the Department of State and funded by USAID, therefore has the potential to deter irregular migration. If regular temporary pathways were more transparent and readily understood in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—and if applications for these visas were processed more quickly—they could be competitive with irregular migration pathways.

Yet this is not the communications approach that the US government currently undertakes in the Northern Triangle. For example, language included in the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 stipulated that 50 percent of the “assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras” could not be obligated until the Secretary of State certified that each government was taking several steps to address corruption, protect rights, and promote the rule of law, including informing its citizens of the dangers of the journey to the southern border. However, there is strong evidence that such general disincentivizing campaigns do not have a meaningful impact on migrant decision-making.[29] Money would be better spent on informative campaigns surrounding the legal pathways that are available, rather than those that are not.

In the long term, introduce new bilateral agreements based on the Global Skill Partnership model

Prior to COVID-19, nearly every industry in the US had a labor shortage, particularly for low-paid, labor-intensive positions such as health care aides, restaurant workers, and hotel staff.[30] This is due to the fact that more Americans are going to college and taking high-paid jobs while working-class baby boomers are retiring en masse.[31] By 2050, 75 percent of the US workforce will be 65 or older, resulting in labor shortages to the tune of 400 million workers.[32]

On the other hand, demographic projections forecast that by 2040, the number of working-age people in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras will expand by 9 million.[33] Across all low- and middle-income countries, the number is predicted to expand by 625 million. And as these countries grow richer, their rates of migration will likely increase.[34]

Some of this movement is likely to take place irregularly unless new legal channels for migration are created. If these pathways were linked to industries in the US facing labor shortages, the result could be higher incomes for migrants[35] and an expansion of economic activity that could lead to the creation of higher-paying jobs[36] for US citizens.

Design a Global Skill Partnership to plug skills gaps

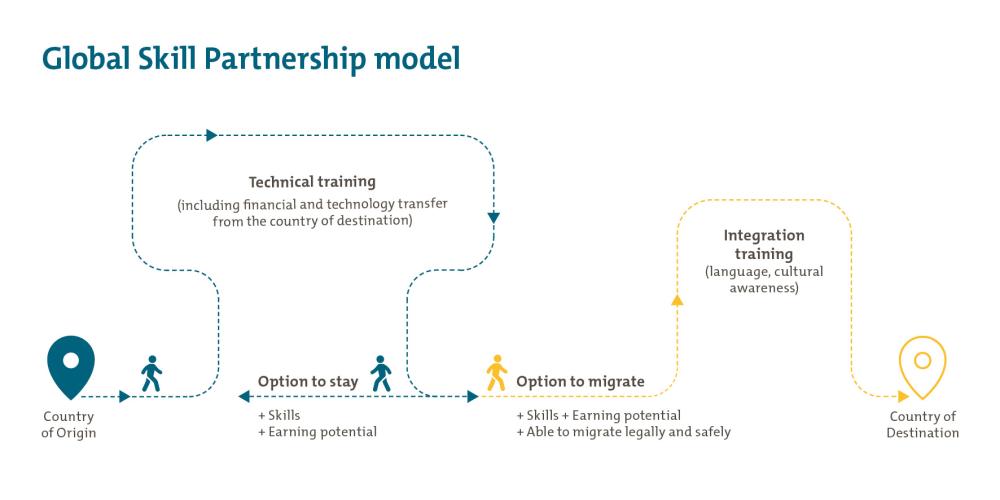

This new legal channel should follow CGD’s Global Skill Partnership model (figure 2), currently being implemented by other high-income countries such as Australia, Belgium, and Germany.[37] A Global Skill Partnership is a bilateral labor migration agreement between a country of origin and a country of destination. The country of origin agrees to train people in skills specifically and immediately needed in both the country of origin and destination. Some of those trainees choose to stay and increase human capital in the country of origin (the “home” track); others migrate to the country of destination (the “away” track). The country of destination provides technology and finance for the training and receives migrants with the skills to contribute to the maximum extent and integrate quickly.

Figure 2. The Global Skill Partnership model

As an example, the US could decide to enter into a nursing bilateral labor agreement with El Salvador. The US would train new nurses in El Salvador up to a specific skill level needed to work in the US labor market. Half of the newly qualified nurses would stay in El Salvador (the “home” track), providing a welcome boost to the number of trained nurses there and facilitating economic development. The other half would migrate to the US (the “away” track) after receiving training in English and other soft skills. Thanks to their targeted training, they would plug gaps in the US labor market and integrate well upon arrival.

The Biden administration should instruct the Department of Labor to coordinate Global Skill Partnerships. Set-up, coordination, and planning infrastructure could be funded by USAID through overseas development assistance. The costs of technical and vocational education could be covered by USAID (for those in the “home” track) and US employers (for those in the “away” track). US employers would also cover the costs of migration, similar to how the H-2 program operates now.

Global Skill Partnerships would complement an expansion of the H-2 program to the Northern Triangle as they provide an option that is non-temporary and targeted to specific labor shortages in the US. Such an approach would increase the productivity of US employers, enabling them to facilitate investment and hire more local workers. This will help the US economy recover from COVID-19 and provide a sustainable labor force from which to draw in the long term.

Policy recommendations

Migration from the Northern Triangle can either continue to create chaos at the southern border or be harnessed to benefit US communities and migrants alike. To ensure the latter, we propose that the Biden administration facilitate increased legal migration through existing and new pathways. This will require coordinated action across several departments.

-

The Department of Labor, along with other appropriate US agencies such as the US Department of Agriculture, must assess demand for laborers across the US economy to establish evidence-based criterion for workers applying for or extending valid H-2 visa status or applying for a Global Skill Partnership program.

-

The Department of Homeland Security must increase the efficiency of application processing within US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) so as to meet labor market demands in a timely fashion.[38] This requires limiting the barriers to application (shortening application forms, cutting processing times, keeping visa fees moderate) and increasing US employers’ (and their representatives) access to assistance from USCIS when they have questions about the H-2 visa program.

-

The Department of State must work with the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to facilitate recruitment of eligible employees through funding the mandate for bilateral agreements and collaborating with regional partners to implement Global Skill Partnerships. This can be prioritized through USAID funding; similarly funded agreements are already in place under the Alliance for Prosperity initiative introduced in 2014 under the US Strategy for Engagement in Central America. However, they fall short of responding to regional and US labor market demands. Further, the proposed bilateral agreements would create an apparatus to replace and shut out unscrupulous recruiters.

- The administration should work with Congress to pass legislation introducing segmented visa portability for H-2 visas and creating a new visa with a special safeguard cap to support the Global Skill Partnership model. Akin to the W nonimmigrant worker visa proposed in the Senate in 2013, a new visa would create a regular migration pathway for low-paid workers and also allow beneficiaries to leave their jobs to work for other employers registered with the program, creating a pool of labor that is responsive to labor market needs. A safeguard cap would protect against sudden inflows of workers while preserving responsiveness to changing conditions.

New legal pathways for migrants from the Northern Triangle will require coordination between US government institutions, private sector employers, and partner countries. While there is precedent for such cooperation, it will undoubtedly be a challenging task. Yet expanding such pathways, in conjunction with border enforcement, is the only way to effectively and permanently resolve the crisis at the southern border and ensure migration is mutually beneficial.

Additional reading

-

Michael Clemens, Cindy Huang, Jimmy Graham, and Kate Gough, 2019. Migration Is What You Make It: Seven Policy Decisions that Turned Challenges into Opportunities. CGD Note. Center for Global Development.

-

Center for Global Development, 2019. A Guide to Global Skill Partnerships.

-

Michael Clemens and Jimmy Graham, 2019. Three Facts You Haven’t Heard Much About Are Keys to Better Policy Toward Central America. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

- Carlos Gutierrez, Ernesto Zedillo, and Michael Clemens, 2018. Shared Border, Shared Future: A Blueprint for Regulating US-Mexico Labor Mobility. CGD Working Group report. Center for Global Development.

The authors would like to acknowledge contributions from Sean Bartlett, Erin Collinson, Helen Dempster, Jocelyn Estes, Eva Taylor Grant, Scott Morris, and Emily Schabacker.

[1] United States Census Bureau, 2019. Place of Birth for the Foreign-Born Population in the United States, Table ID: B05006

[2] Congressional Research Service, 2019. Immigration: Recent Apprehension Trends at The U.S. Southwest Border.

[3] Laura Gottesdiener, Lizbeth Diaz, and Sarah Kinosian, 2020. “Central Americans Edge North as Pandemic Spurs Economic Collapse.” Thomson Reuters, October 3, 2020.

[4] Congressional Research Service, 2019.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Helen Dempster, 2020. Four Reasons to Keep Developing Legal Migration Pathways During COVID-19. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[7] “The Biden Plan for Mobilizing American Talent and Heart to Create a 21st Century Caregiving and Education Workforce.” Joe Biden for President: Official Campaign Website, October 18, 2020.

[8] Helen Dempster, 2020.

[9] Miriam Jordan, 2020. “Farmworkers, Mostly Undocumented, Become 'Essential' During Pandemic.” The New York Times, April 2, 2020.

[10] Marion Joppe, 2012. “Migrant workers: Challenges and opportunities in addressing tourism labour shortages.” Tourism Management. 33.

[11] Jeanne Batalova, 2020. Immigrant Health-Care Workers in the United States. Migration Policy Institute.

[12] Miriam Jordan, 2020.

[13] Michael Clemens, 2012. Why I'm Thrilled the United States Has Stopped Excluding Haitians from Temporary Work Visas. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[14] Michael Clemens, 2013. The Effect of Foreign Labor on Native Employment: A Job-Specific Approach and Application to North Carolina Farms. CGD Working Paper 326. Center for Global Development.

[15] Ibid.

[16] US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020. “Employment Projections by detailed occupation, 2019 and projected 2029.” Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2020.

[17] “The Biden Plan to Build Security and Prosperity in Partnership with the People of Central America.” Joe Biden for President: Official Campaign Website, October 18, 2020.

[18] Michael Clemens and Mariapia Mendola, 2020. Migration from Developing Countries: Selection, Income Elasticity, and Simpson’s Paradox. CGD Working Paper 539. Center for Global Development.

[19] Michael Clemens, 2020. The Emigration Life Cycle: How Development Shapes Emigration from Poor Countries. CGD Working Paper 540. Center for Global Development.

[20] Michael Clemens and Kate Gough, 2018. Can Regular Migration Channels Reduce Irregular Migration? Lessons for Europe from the United States. CGD Brief. Center for Global Development.

[21] John Gibson and David McKenzie 2010. “The Development Impact of a Best Practice Seasonal Worker Policy: New Zealand’s Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) Scheme”. Working Papers in Economics 10/08, University of Waikato, Department of Economics.

[22] Michael Clemens and Kate Gough, 2018. Don't Miss This Chance to Create a 21st Century US Farm Work Visa. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[23] International Organization for Migration, 2008. Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program, Guatemala-Canada.

[24] US Embassy Guatemala, 2019 “U.S. Department of Labor and Guatemala Sign Joint Memorandum of Agreement to Improve H-2A Visa Program.” Press release, July 31, 2019.

[25] US Embassy El Salvador, 2020. “The United States and El Salvador Sign MOU on Temporary Workers Program.” Press release, February 6, 2020.

[26] Carlos Gutierrez, Ernesto Zedillo, and Michael Clemens, 2018. Shared Border, Shared Future: A Blueprint for Regulating US-Mexico Labor Mobility. CGD Working Group report. Center for Global Development.

[27] Michael Clemens and Jimmy Graham, 2019. “Three Facts You Haven’t Heard Much About Are Keys to Better Policy Toward Central America,” CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[28] Victoria A. Greenfield, Blas Nunez-Neto, Ian Mitch, Joseph C. Chang, and Etienne Rosas, 2019. Human Smuggling and Associated Revenues: What Do or Can We Know About Routes from Central America to the United States? Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center, RAND Corporation.

[29] Claire Mcloughlin, 2015. “Information Campaigns and Migration.” GSDRC. GSDRC Applied Knowledge Services, August 3, 2015.

[30] US Department of Labor, 2020.

[31] Zuzana Cepala, 2019. The Looming Demographic Crisis in High-Income Countries. LaMP Policy Note 001. Labor Mobility Partnerships.

[32] Ibid.

[33] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2019. Probabilistic Population Projections Rev. 1 based on the World Population Prospects 2019 Rev. 1.

[34] Michael Clemens, 2014. Does Development Reduce Migration? CGD Working Paper 359. Center for Global Development.

[35] Francesco Fasani, 2014. Understanding the Role of Immigrants' Legal Status: Evidence from Policy Experiments. IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

[36] Michael Clemens, 2013.

[37] Center for Global Development, Migration, Displacement, and Humanitarian Policy Program, 2020. Global Skills Partnerships.

[38] USCIS is running at a budget deficit; however, the increased tax revenue generated by the Biden administration’s proposal to grant undocumented workers a pathway to citizenship could offset additional costs.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.