The World Bank is a multilateral organization that provides financial and technical assistance to developing countries. As the World Bank’s largest shareholder, the United States maintains a unique influence in shaping its agenda and has a vested interest in ensuring the institution is well managed and appropriately resourced. The US Congress has an important role both in funding US contributions to the World Bank and in overseeing US participation in the institution. Past congressional decisions tied to US funding have led to changes in World Bank policies and institutional reforms.

Several inflection points warrant increased congressional attention to the World Bank. The general capital increase agreement formalized in October 2018—a multilateral commitment to increase contributions from all bank shareholders (including the US) to enable more lending by the bank—is one such point. This agreement requires congressional authorization and the appropriation of new contributions, which will mainly benefit the middle-income and lower-middle income country recipients of the bank’s lending. A second opportunity centers on replenishing the bank’s soft lending window for fiscal years 2021 through 2023, which will primarily benefit low-income countries. The IDA19 pledging session will take place in December, and Congress will be called upon to appropriate funding to enable the US to fulfill its commitment.

The World Bank Group

The World Bank Group is made up of five entities with complementary roles in promoting global economic development. The International Development Association (IDA) provides grants and low-cost loans to low-income countries. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) plays a similar role but provides loans to middle-income countries. Select creditworthy low-income countries are eligible for a blend of assistance from IBRD and IDA. To account for the differences in recipient country incomes, IBRD loans typically cost more than IDA loans; however, both offer more favorable terms than private sector lending.

The World Bank Group also comprises three other organizations: the International Finance Corporation, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) provides loans to private companies, as opposed to sovereign nations, in the developing world. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) provides guarantees to private investors who lend to the developing world, incentivizing risk-averse companies and individuals to invest in developing markets. Finally, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) acts as a third-party dispute settlement recourse for investors and sovereign nations, to promote international investment by increasing confidence in an impartial dispute resolution process.

Table 1. World Bank Group fast facts

IDA, the World Bank’s soft lending window, provides grants and highly concessional loans (with low interest rates and long repayment periods) to the world’s poorest countries, whose annual per capita incomes fall below an established threshold ($1,145 in FY2019[1]). It is one of the largest sources of development assistance for these countries, most of which are in sub-Saharan Africa. IDA loans are interest-free or offered at below-market rates and have a maximum maturity of 40 years with grace periods ranging from 5 to 10 years.[2]The IBRD is the bank’s hard lending window. It borrows on international capital markets at attractive rates and relends to emerging market economies, charging a slight premium to cover the World Bank’s operating expenses and to generate funds for other purposes, including grants to poorer countries.

Membership

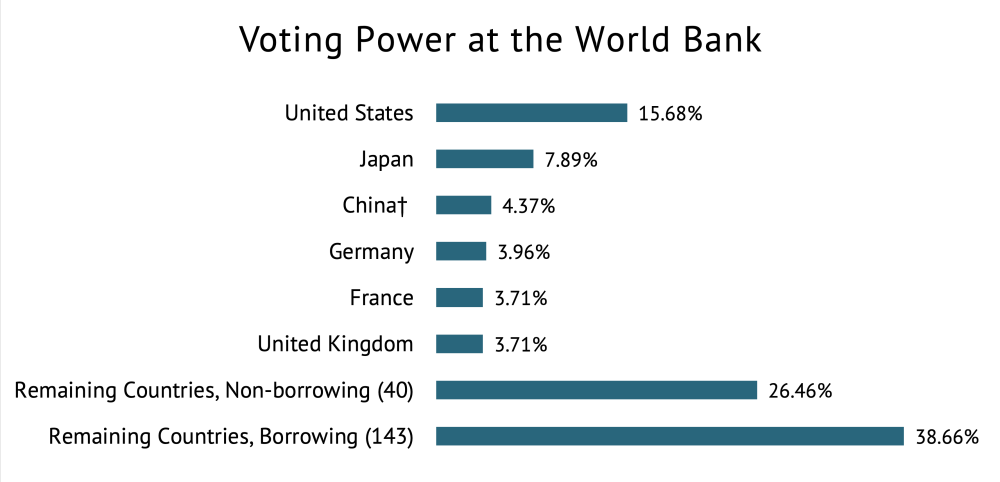

The World Bank is owned by 189 member governments.[3] Each member is a shareholder, with the number of shares based roughly on the capital pledged to back up the World Bank’s borrowing on capital markets. This arrangement generally gives proportionally greater decision-making power to nonborrowing and high-income countries. The United States has the largest voting share (see figure 1). Since any change in the bank’s Articles of Agreement requires an 85-percent majority, the United States is the only single member country with veto power over changes to the bank’s structure.

Figure 1. Voting power at the World Bank

Source: WBG, “A Report to Governors on Shareholding at the Spring Meetings 2018”

Note: China also borrows from the World Bank. See Morris, S. and Portance, G. (2019) “Examining World Bank Lending to China: Graduation or Modulation?”

Governance

The leadership at the World Bank is made up of the board of governors, the board of executive directors, and the president. The board of governors, the highest decision-making body, consists of one governor for each member country, generally a minister of finance. Governors, who meet annually, delegate day-to-day authority over operational policy, lending, and other business matters to the board of executive directors, who work on-site at the institution’s headquarters. There are 25 members on the World Bank’s board of executive directors, representing all member countries. While most countries are represented on the board as part of a “constituency,” the US executive director exclusively represents the United States.

The president of the World Bank is responsible for the overall management of the institution and chairs the board of directors. Historically, the president is selected based on an informal understanding between the United States and Europe that allows the United States to name the president of the World Bank and the European governments to name the president of the International Monetary Fund. The selectee is approved and appointed by the board of directors to serve a five-year term, renewable once. In April 2019, the World Bank confirmed David Malpass as president, maintaining the tradition of selecting the US nominee.

Box 1. IDA and vulnerable populations

IDA’s concessional lending and grants focus on five cross-cutting themes—climate, gender, fragility and conflicted areas, jobs and economic transformation, and governance and institutions—to ensure that projects assist the most vulnerable populations.

Through its global health programs, IDA contributes to gender equality in the developing world by promoting maternal health and equitable access to healthcare. In 2018, 36.88 million individuals received essential health services, including 23.18 million women and girls.[4] Female life expectancy at birth in IDA countries increased from an average of 70 years in 2000 to 75 years in 2016, bringing life expectancy for women in IDA countries higher than the average life expectancy of women living in middle-income countries (73) and within range of life expectancy in upper-middle-income countries (78).[5]

Since climate change disproportionally affects populations in the countries served by IDA, who are likely to be more vulnerable to natural disasters and food scarcity, IDA focuses on supporting climate mitigation and adaptation. In Africa and South Asia, there will be an estimated 125 million internal climate migrants by 2050. IDA has encouraged recipient governments to incorporate a climate lens into policy reforms, to reduce emissions and prepare for climate change impacts.

World Bank Operations

The amount of World Bank lending varies widely from year to year and depends on demand. In recent years, IBRD and IDA lending has ranged from a low of $22.3 billion in 2005[6] to a high of $47.0 billion in 2018.[7] Both ramped up lending to help developing countries cope with the effects of the global financial crisis. In 2018, World Bank commitments totaled $66.9 billion, with 34 percent of its lending ($23.0 billion) coming from IBRD and 36 percent ($24.0 billion) from IDA[8] (see figure 2).

Figure 2. World Bank commitments, 2018

Areas of focus: In FY2018, the sectors receiving the greatest shares of World Bank lending were energy and extractives (15 percent) and public administration (15 percent). While the World Bank lent to 103 countries, African countries borrowed the most, accounting for 35 percent of total lending.[9] In recent years, the World Bank has increased its response to emerging crises with mechanisms to support countries hosting large populations of refugees, to finance efforts to prevent global pandemics, and to mitigate famine.

Support for countries hosting refugees: Announced in September 2016, the Global Concessional Financing Facility provides lower-rate loans to middle-income countries to help meet the development needs of refugees and host communities, recognizing the public goods generated by the investments. By promoting refugee protection and well-being, countries like Jordan provide benefits beyond their borders, supporting regional stability and fulfilling international moral and legal obligations.[10]

Increased focus on fragile states: As more countries “graduate” from IDA concessional financing to non-concessional IBRD loans, the remaining nations receiving IDA assistance trend towards fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS). Increased development funding for these countries aims to support global peace and security, and humanitarian objectives. Since 2016, the most recent round of IDA replenishment funding, the World Bank has doubled resources for FCAS to over $14 billion.[11]

Leadership in addressing climate change: The World Bank Group has committed to assisting borrowing nations with financing, technical assistance, and knowledge sharing to help countries achieve their own climate goals set under the Paris Agreement. Financing in this area has doubled under the bank’s most recent decision to direct $200 billion in the next five years towards climate action projects, primarily in areas of renewable energy and transportation, and $50 billion towards climate adaptation and mitigation projects to protect the world’s most vulnerable populations, by strengthening early warning systems and putting in place community-level disaster risk management plans in the Pacific.[12]

Supporting women entrepreneurs: At the 2017 G20 Summit, the World Bank officially launched the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative (We-Fi) to mobilize over $1 billion to increase access to capital for women-owned small and medium-size businesses in the developing world. We-Fi brings together the strengths of the public and private sector with the goal of lifting thousands of women out of poverty by enabling them to grow their own businesses.

How Is the World Bank Funded?

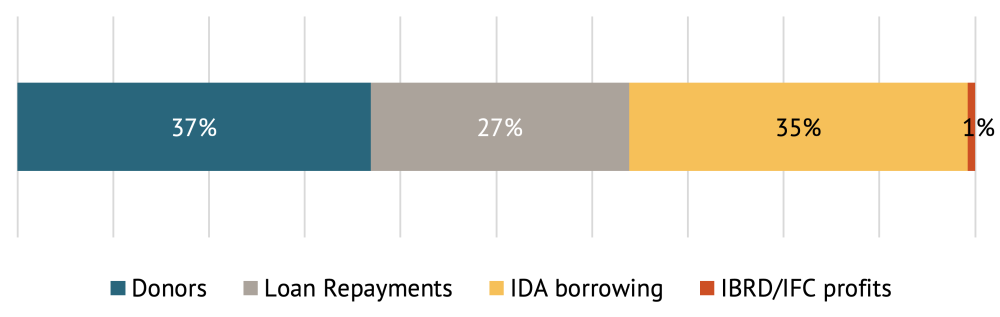

IDA grants and loans are funded largely by contributions from richer donor countries, supplemented by loan repayments and IBRD/IFC profits (see figure 3). Because IDA funds are offered as grants or below-market-rate loans, its resources need to be periodically replenished through donor contributions. These “replenishments” take place every three years. The last IDA replenishment (IDA18) negotiations, in 2016, brought in $75 billion, with the United States pledging $3.87 billion over three years.[13] While the United States has historically made the highest contributions to IDA, recent contributions have fallen below its historical share. During IDA18, the United Kingdom pledged more than the United States.

In November 2018, IDA formally launched its 19th replenishment cycle.[14] Donors from across the globe will meet three times in 2019, culminating in a pledging session in December where they will announce their IDA contributions for the next three years. Any US commitment will require congressional appropriations. Country representatives will consider several development priorities during the IDA19 discussions, including the role that IDA should play in responding to increasing debt vulnerabilities in low-income countries.[15]

Figure 3. Where does IDA get its money?

The IBRD leverages the capital provided by the United States and other shareholders by issuing bonds in the bond markets; the proceeds enable the IBRD to lend to its client countries, which are creditworthy and largely middle-income. These countries, in turn, provide funding to the IBRD in the form of loan repayments, which fund administrative expenses, contribute to the capital base, and subsidize IDA. This “leverage” model has enabled shareholder capital contributions of $16.5 billion[16] (of which, the United States has contributed about $2.9 billion)[17] to support $681.3 billion in lending since 1947.[18]

Because original shareholder contributions can be leveraged in this way, the World Bank does not require frequent replenishment of its capital base. But periodically, the World Bank will issue additional shares to country shareholders, known as a general capital increase. The United States and other World Bank shareholders have purchased shares in the IBRD five times since its creation in 1944. Most recently, in April 2018, the United States and other World Bank shareholders agreed to a capital increase for the IBRD (along with a capital increase for the IFC). The final deal involved policy measures aimed at strengthening the World Bank’s capacity to fight poverty across different dimensions, including reforms to lending rules that will require certain borrowers to pay more and targets to reduce lending to countries above a per capita income threshold. Congress will need to provide authorization and funding to allow the administration to deliver on its promise under the agreement.

Erin Collinson, Alysha Gardner, and Scott Morris contributed to this brief.

[3] WBG, “Who We Are – Member Countries.”

[4] WBG, “RMS – Tier 2”

[7] WBG, Annual Report 2018

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[11] WBG, Annual Report 2018

[12] WBG, “Climate Change”

[13] WBG, “Contributor Countries”

[14] WBG, “IDA19 Replenishment”

[16] WBG, Annual Report 2018

[17] Congressional Research Service, “2018 World Bank Capital Increase Proposal”

[18] WBG, “Annual Report 2017”

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.