More from the series

WORKING PAPERS

Governments around the world continue to focus on tackling the COVID-19 outbreak head-on and preventing already-stretched health systems from being even more overwhelmed. But as the pandemic accelerates, governments must also balance COVID-19 responses with wider health needs. Sexual and reproductive health and rights are especially at risk for women and girls, who are disproportionately affected by the crisis in a myriad of ways, including school closures, increased unpaid care duties, and gender-based violence. COVID-19 has presented new challenges for sexual and reproductive healthcare, while also amplifying longstanding barriers. In early June, CGD hosted an online panel to discuss how policymakers, development partners, and the private sector can sustain and expand sexual and reproductive health and rights through the pandemic and beyond. Here are four key takeaways:

1. Keep sight of COVID-19’s disruptions on sexual and reproductive health gains

As we know from previous outbreaks, knock-on effects of the pandemic could cause just as much, if not more, illness and death than the disease itself. Based on rapid surveys in the Global Financing Facility’s (GFF) 36 partner countries, Monique Vledder, Practice Manager of the GFF, stressed that COVID-19 is already triggering a secondary health crisis through widespread disruptions to RMNCAH care. These indirect health impacts are driven by interruptions to the supply of services, including health facility capacity, redeployment of health workers, and supply chain constraints, alongside demand-side challenges, including transport restrictions, lack of information about service availability, and reduced household income. Salma Anas-Kolo, Director of the Department of Family Health at the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health, shared that many women and families in Nigeria are not aware that sexual and reproductive health services are still available. Further, some healthcare workers in Nigeria have been diverted to contribute to the COVID-19 response, while others are hesitant to deliver services, especially given PPE shortages.

While global supply chains for many essential health products have been strained by the current crisis, Prashant Yadav, Senior Fellow at CGD, explained that sexual and reproductive health products are particularly at risk. For example, the global procurement architecture of sexual and reproductive health products is more fragmented than the existing apparatuses for some other health areas, such as HIV, TB, and malaria. Ongoing efforts by UNFPA and the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition (RHSC), including the Global Family Planning Visibility and Analytics Network, have been critical in the face of COVID-19. But these mainly focus on contraceptive supplies; gaps persist for other sexual and reproductive health products, such as medical abortion (MA). Further, potential quality issues could lead to adverse health outcomes and, in turn, erode hard-won gains in patient trust and confidence in products like MA—derailing progress far beyond the current crisis.

Stories from the frontline of COVID-19-related disruptions to sexual and reproductive health demand, access, and supply abound, but a fuller picture of their magnitude remains to be seen in the data. Emerging evidence from RHSC and Nivi alongside findings from previous crises tell a cautionary tale. Some data currently suggests there may be a short-term buffer of supplies, but Yadav cautioned that this could be due to a time-lag effect given the scale of global supply chain issues. To better target and implement health supply chain mitigation measures amidst COVID-19, CGD colleagues are working with IQVIA, Maisha Meds and other data platforms to develop an early alert system for country-level shortages of non-COVID health products, including sexual and reproductive health—stay tuned for more from CGD in this area.

2. Double down on integrating health systems with the innovation ecosystem

As COVID-19 restricts the movement of people, providers, and products, the agility and creativity of the private sector has already helped to augment government health system capacity. From telepharmacies and direct-to-consumer delivery to self-care products, chatbots, and drones, growth capital for social enterprises is one way to harness the current entrepreneurial groundswell to address COVID-19, maintain the provision of essential health services, and cushion the economic blow. Mary-Ann Etiebet, Executive Director of Merck for Mothers and Board Member at CGD, shared that the private sector’s ability to rise to the occasion builds, in part, on existing innovative financing vehicles, such as the public-private $50 million MOMS Initiative to help companies like LifeBank scale.

But Etiebet and Vledder cautioned that without intentionally integrating digital models and tools into the larger health system, these models could exacerbate existing inequities. Given that these innovations (and private providers generally) are seldom covered by public financing from governments and development partners, leveraging digital platforms will require careful consideration of how marginalized groups can realistically gain access to private options available to wealthier, more educated, and urban populations. Speakers highlighted the potential of blended funding flows from governments, development partners, and the private sector to better connect digital tools with national health systems. This pooling of resources could be channeled into health savings accounts and demand-side financing mechanisms like coupons and vouchers, for example. These new healthcare delivery and financing approaches are especially compelling because they build sexual and reproductive healthcare around the choices, preferences, and agency of women and girls. Etiebet emphasized that, even beyond the health system, collaboration across the finance, technology, pharmaceutical, and public health sectors can help ensure that new resources reach the last mile.

3. Boost local ideas for global impact

The new digital tools and delivery models described above depend on local innovators and social entrepreneurs who have a nuanced understanding of the unique challenges in their own communities. Vledder shared that the GFF has expanded its online knowledge and learning infrastructure to host an action-oriented community of practice through which countries discuss how to adapt and strengthen service delivery. While the collaborative platform facilitates bottom-up, country-driven solutions, it also gives the GFF more on-the-ground insights to better tailor financial and technical support.

Speakers also pointed to examples of local production and manufacturing of health products, including PPE. Yadav explained that streamlining supply chains through local and regional production could help mitigate supply chain shortages for both PPE and sexual and reproductive health products. In Nigeria, the government is collaborating with the trade industry, manufacturing companies, and private distributors to build the country’s capacity to produce and deliver PPE, sanitizer, and other infection control products. The GFF, in partnership with the IFC, is supporting local companies in Africa to expand their manufacturing capabilities. Further, as my colleagues have previously argued, DFIs can support health service continuity amidst the pandemic by financing the production scale-up of PPE and sanitation supplies, among other win-win equitable investments.

4. Forge a holistic, sector-wide path forward

Primary health care remains under-prioritized in many countries due to numerous political economy factors, despite being the delivery point at which many vulnerable groups access sexual and reproductive health services and other essential care. This is particularly relevant in the context of COVID-19; the existing prioritization of hospitals in many LMIC health budgets, combined with growing demands for resource-intensive tertiary care for COVID-19 treatment, may divert resources away from primary care. Vledder underscored the GFF’s focus on transformations in primary care delivery, and Anas-Kolo described the centrality of primary healthcare for Nigeria’s UHC agenda (although newly announced budget cuts may threaten essential services).

Relatedly, speakers highlighted the importance of managing healthcare holistically. Calls for a system-wide approach in global health are not new, but the need to create sustainable health systems with more and better domestic spending resonates now more than ever. High levels of dependence on donor funding for contraceptives, as noted by Vledder, coupled with unpredictable political environments in donor countries and growing uncertainties around the future of development assistance put sexual and reproductive healthcare at risk. The challenges of COVID-19 amplify the importance of integration across health programs and between sectors. In the words of Etiebet, “We’re not trying to solve for diseases; we’re trying to solve for people, for health, and for life.”

Despite the unprecedented challenges the global community is facing, the best way forward seems clear: Let women and girls lead the way towards universal access to high-quality, affordable sexual and reproductive healthcare, and follow them with flexible and innovative financing as part of a coherent health system aligned with how they approach their own wellbeing.

In case you missed it, you can watch the full recap of the event here and check out live Twitter highlights here.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

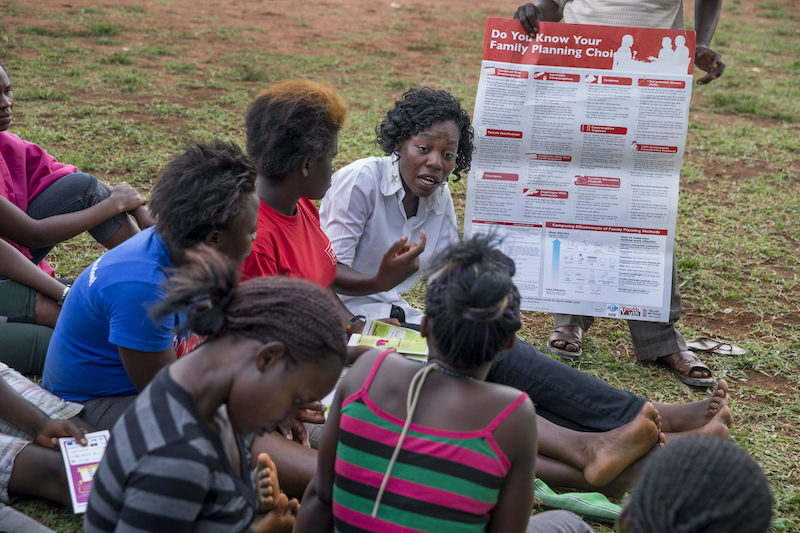

Image credit for social media/web: Yagazie Emezi/Getty Images/Images of Empowerment