Recommended

One month ago, we launched a survey asking education service providers about their biggest concerns and challenges in light of the COVID-19 crisis. We shared the survey through Twitter, CGD and external mailing lists, and direct outreach to key education coalitions and networks. Over 100 individuals from 82 organizations in at least 32 countries responded. Respondents included those working with school operators, nongovernmental organizations, childcare practitioners, and other providers of education, children’s rights, and gender equality programming. Thanks to their responses, we now have a better understanding of how COVID-19 is affecting education service operations—and what providers are doing in response.

The survey data can help inform and improve decision-making by governments and donor institutions and in turn allow them to respond to the needs of frontline organizations and the children they serve. Though our sample of respondents should not be taken as representative of all education service providers’ perspectives, this data can help to guide future priorities for more systematic research, and in the meantime, provide preliminary insights to bolster rapid response efforts.

You can find the full report outlining all of our findings here and underlying (anonymized) data here. Below we highlight key survey findings:

1. Most respondents believe that girls are more likely to be negatively affected by COVID-19 school closures than boys

COVID-19 has shed light on, and in many instances magnified, pre-existing discriminatory social norms, gender roles, and power dynamics. Given that local organizations are rooted in communities and understand gender inequalities within these contexts, it is not surprising that 69 percent of education service providers report that girls are at a greater risk of harm due to school closures than boys. (This trend is also consistent with a rich evidence base underscoring the importance of educational access and attainment for girls’ wellbeing.)

Why do education service providers assert that girls are more likely to be at risk?

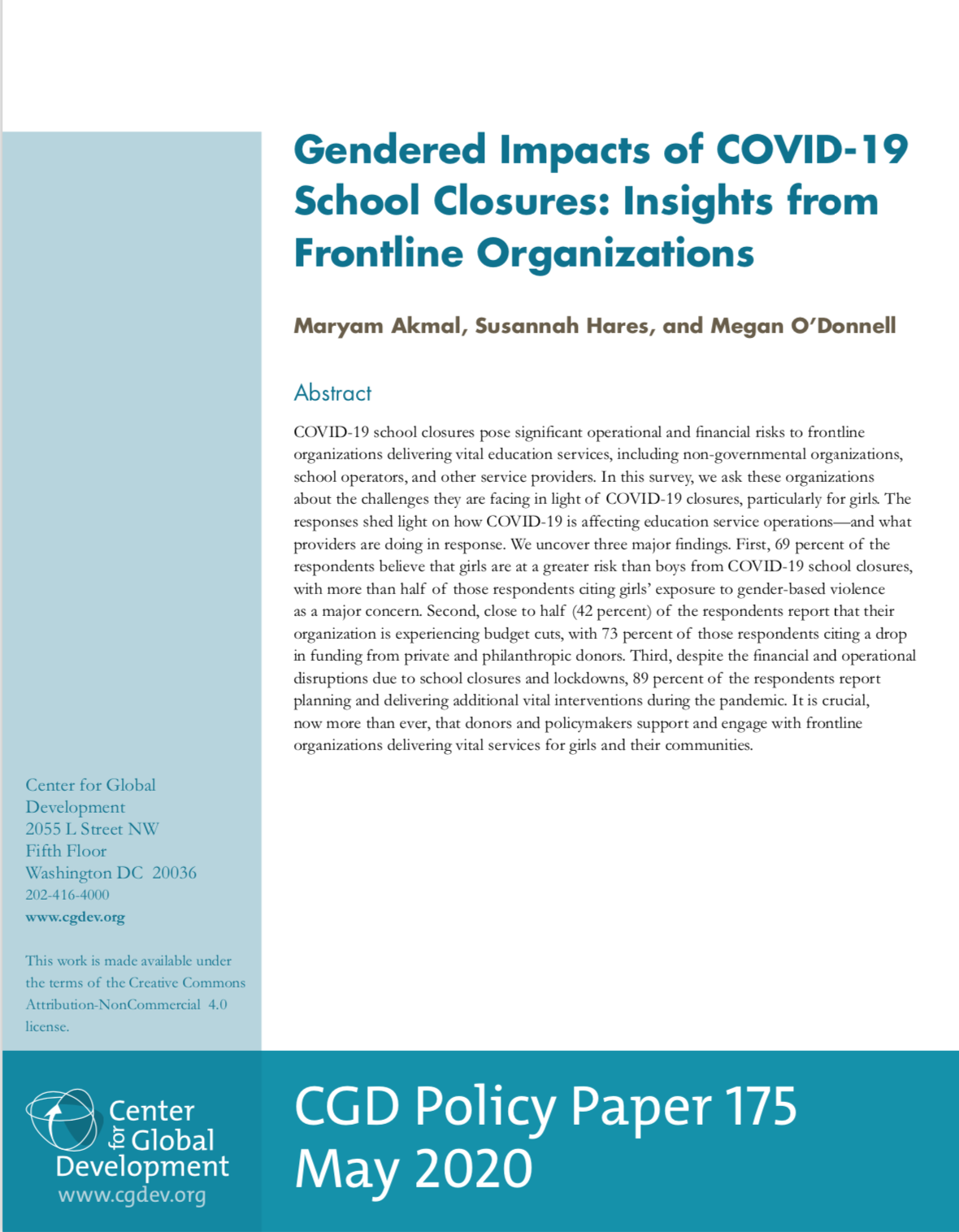

Figure 1. Key risks for girls due to school closures

Note: Graph is based on a sample size of 95 respondents for marriage and gender-based violence (GBV); 96 respondents for learning, not coming back to school, and pregnancy; and 97 respondents for labor market. Numbers may not add to 100 percent due to rounding.

Vulnerability to gender-based violence: Nearly four-fifths (78 percent) of respondents consider the risk of violence against girls to be “important” or “very important.” Their perspectives align with evidence from past pandemics and other crises, which suggests that girls are more likely to be at risk of violence in these contexts. Though gender-based violence is its own ever-present public health crisis, pandemics heighten this risk. Without schools and other education programs as a safe space for girls, they are likely to spend more time with older men, and, facing economic distress, family members may be more likely to pressure girls into engaging in transactional sex to meet basic needs. Families may also be more likely to force girls into early marriages in times of economic strain.

Predictions that girls might not return to school: About half (48 percent) of respondents express concerns that girls might not return to school when they reopen. Gender gaps in school return rates could stem from a number of factors, including parents’ inability to pay school fees or cover other school-related costs for all children; needing some children to stay home or join the labor force due to the economic duress caused by COVID-19; or the fact that girls may have already been pressured into early marriages.

Disproportionate unpaid care work: More than half of the respondents who believe girls are at a greater risk point to girls’ disproportionate unpaid care work burdens and the likelihood that these will increase. As a result of their caregiving responsibilities, girls have less time to devote to studies (not to mention leisure), which risks widening gender gaps in learning outcomes and educational attainment. Caregiving burdens will only increase if girls’ family members are directly infected with COVID-19, or in households where financial strain and food insecurity in slowed economies dictate that children must help provide for basic needs. Education service providers’ responses are consistent with what we know already about the nature of caretaking: adolescent girls act as “big sisters,” contributing heavily to caring for younger siblings and doing domestic work. This must be top of mind when we consider how to mitigate the impact of school closures—as well as address broader economic and social gender gaps across generations.

Respondents also cite other disproportionate impacts of school closures on girls, including the lack of access to menstrual sanitation products that may be provided by now-closed schools and nongovernmental organizations. Some highlight the gender-unequal nature of engagement with technology: girls are less likely to have access to the internet, and when they are online, they face heightened risks of harassment.

Though the majority of those surveyed believe girls are more likely to experience harm than boys as a result of school closures, it is worth noting that some respondents point to different harms for boys: for example, they may be at risk of becoming child laborers, especially in countries where harvest season is underway. It is important to identify and address differential risks that school closures pose for both boys and girls.

2. At the same time, funding to these service providers is being cut, particularly by private and philanthropic donors.

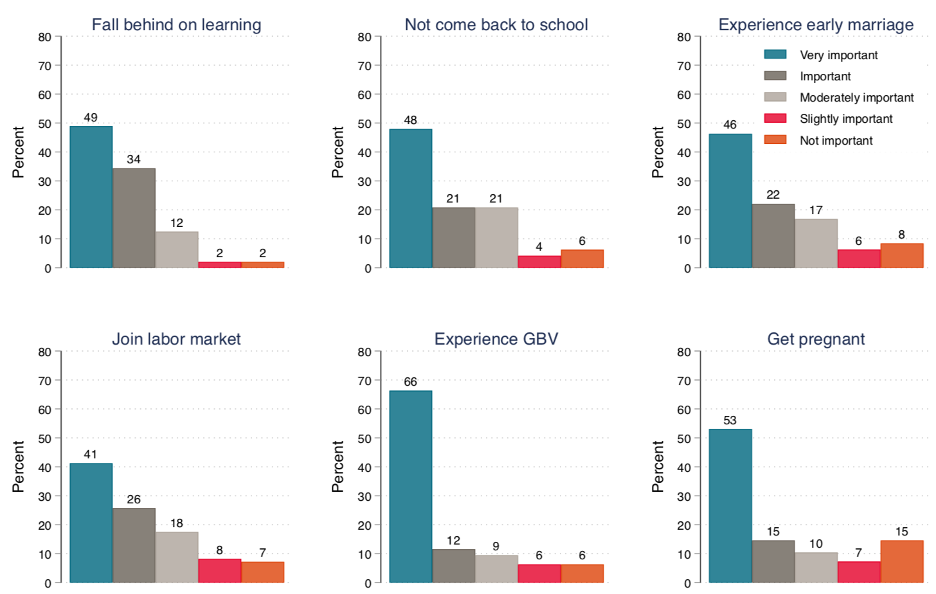

Figure 2. A large percentage of respondents report experiencing budget cuts and not receiving additional funding

Note: Charts are based on a sample size of 97 respondents for budget cuts and 95 respondents for additional funding. Numbers may not add to 100 percent due to rounding.

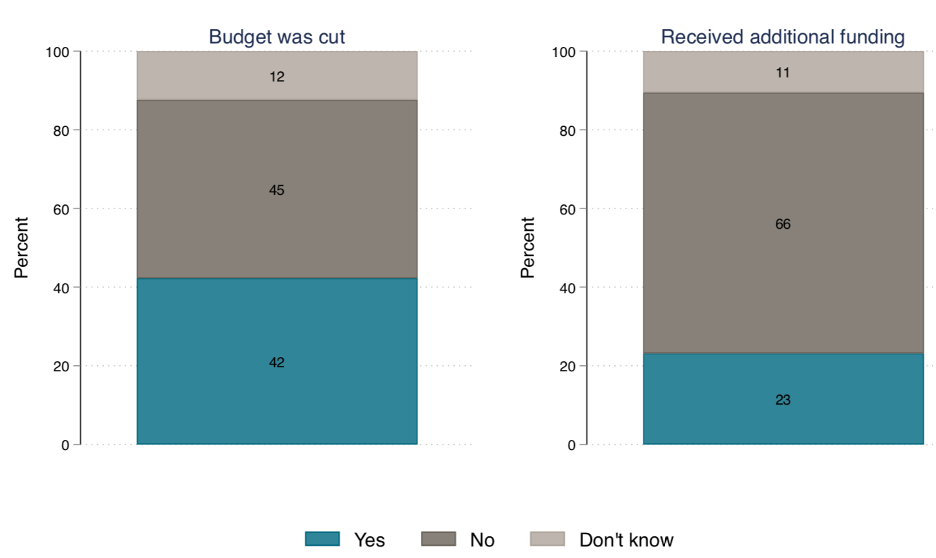

Forty-two percent of respondents reported that their organizations’ budgets have been cut since the pandemic began. Reductions in contributions and fees from parents are to be expected, given school closures and households facing increased economic strain. But surprisingly, only 34 percent of respondents cite budget cuts driven by reduced parental contributions, whereas 73 percent cite cuts from private or philanthropic donors. Some bilateral donors and foundations (the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Mastercard Foundation, Echidna Giving, among others) appear to have increased support to education service providers in light of COVID-19, but survey responses suggest other donors are scaling back and/or redirecting funds away from these organizations instead.

Figure 3. Respondents most often cite cuts from private or philanthropic donors

Note: Graph is based on a sample size of 41 respondents who report budget cuts. Respondents can mention multiple sources of budget cuts (for example, private or philanthropic donors and multilateral or bilateral donors). Therefore, the same respondent can be counted towards multiple categories of budget cuts.

These budget cuts are already having tangible consequences and will likely continue to do so absent intervention: Thirty-three percent of respondents anticipate that their organizations will lay off frontline workers.

3. Despite the budget cuts, education service providers are already mobilizing to address gender-specific risks of school closures.

Eighty-nine percent of respondents report that their organizations have specific programs either planned or already underway to address the gender-specific risks of school closures. These programs are aligned with the specific high-risk areas they cite, such as increased familial violence. Specific efforts include the launch of anti-violence and abuse awareness campaigns, the installation of toll-free hotlines to support victims of violence, weekly phone calls with students, and regularly scheduled communication with parents to check on their home lives, safety, and security. Other programming includes the distribution of essential items (soap, sanitary pads) and food to mitigate the consequences of exacerbated poverty in students’ households; the development of at-home learning materials, including those that use radio and SMS channels for students who lack internet access; and awareness programs that emphasize the importance of girls’ return to school.

Our survey data shows that education organizations’ services extend well beyond reading, writing, and arithmetic lessons. Schools and education programs serve as safe havens, reflected in organizations’ oversight through check-ins to protect children against physical violence or harmful traditional practices like child marriage. They also serve as platforms for health services, like vaccinations, which have now been put on hold due to school closures.

With the focus on lives and livelihoods lost to the pandemic, there is a real risk that donors, governments, and even families will not treat education as a primary concern in the short- and medium-term. As funds get diverted toward COVID-19 health responses and away from education service providers, this will affect both girls and boys, but may affect girls disproportionately more. COVID-19’s health and economics risks are understandably top of mind, but donors’ and policymakers’ should not position the focus on health to come at the expense of support to other sectors, especially not in low- and middle-income countries where the impact of school closures may well outweigh the direct health effects of the disease.

What Can Be Done?

In light of the survey’s findings, what can policymakers and donors do to support the critical functions performed by frontline organizations?

Listen to and support local frontline organizations tackling gendered risks of COVID-19

Girls face heightened risks due to COVID-19 school closures, particularly related to gender-based violence, early marriage, and pregnancy, which have lifelong consequences. Education service providers, rooted in local communities, are positioned to provide and support not only schooling but also immediate food assistance, parental support, health services, social support, and oversight against increased violence—all of which are needed more than ever by the most vulnerable children. While the economic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis have been devastating for many frontline organizations, many are adapting their efforts to mitigate the risks brought on by the pandemic. Donors and policymakers must continue to support these efforts. Donors in particular should exercise “funder humility,” listen to frontline organizations, and allow flexibility with funding decisions.

Adopt an evidence-based, gender-responsive approach across programs, policies and funding decisions

Policymakers and donors should draw on and support the creation of rigorous evidence identifying which programs and approaches are most effective in supporting girls and boys, in gender-responsive ways. Notably, policymakers, donors, and education service providers cannot rely exclusively on interventions that target girls to mitigate the gendered risks of school closures. Because many of the risks girls face are rooted in economic vulnerability, complementary interventions to ensure food security and basic livelihood protection will be required to ensure girls get to return to school and do not face disproportionate harm in the interim. Finally, while frontline organizations step up to provide vital services, it is critical to support the evaluation of these new interventions so we know what works best for future crises.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.