The Obama Administration has left an indelible impact on domestic energy policy and global climate policy. Policies driving technological innovation—in what critics have dubbed the “war on coal”—are helping the United States transition its energy system to one that is cleaner and more efficient. While the administration touts the growth of clean energy deployment in the United States at international fora, it should not limit its engagement with foreign countries on fossil energy—especially when the climate gains could be large. This is particularly critical at a time when multilateral development banks are struggling with the question of whether to finance coal projects as the impacts of climate change worsen, especially for the citizens living in their client countries.

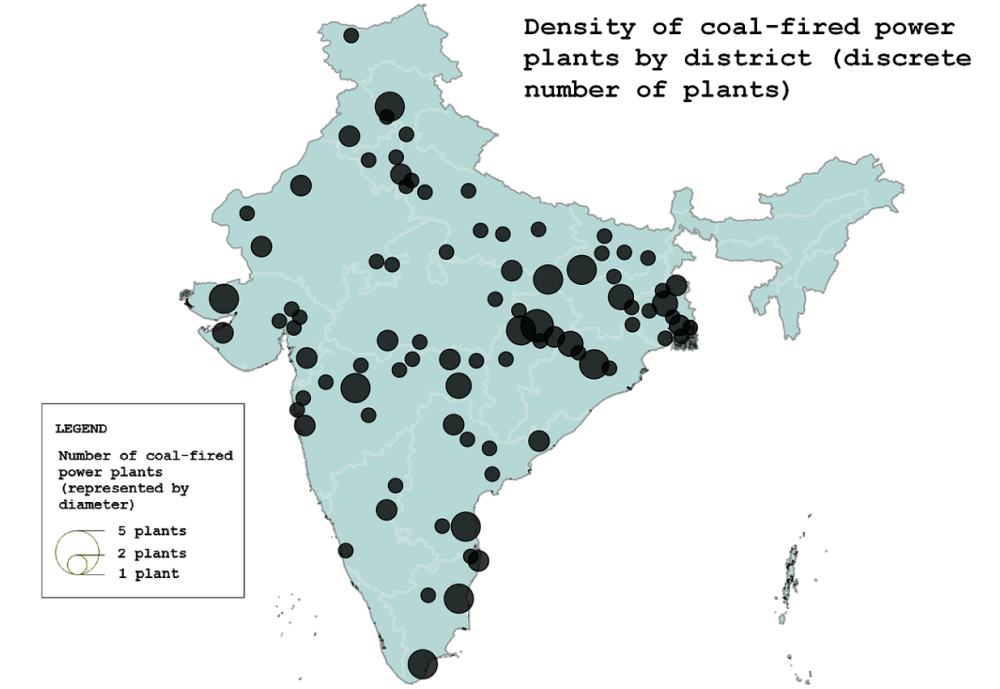

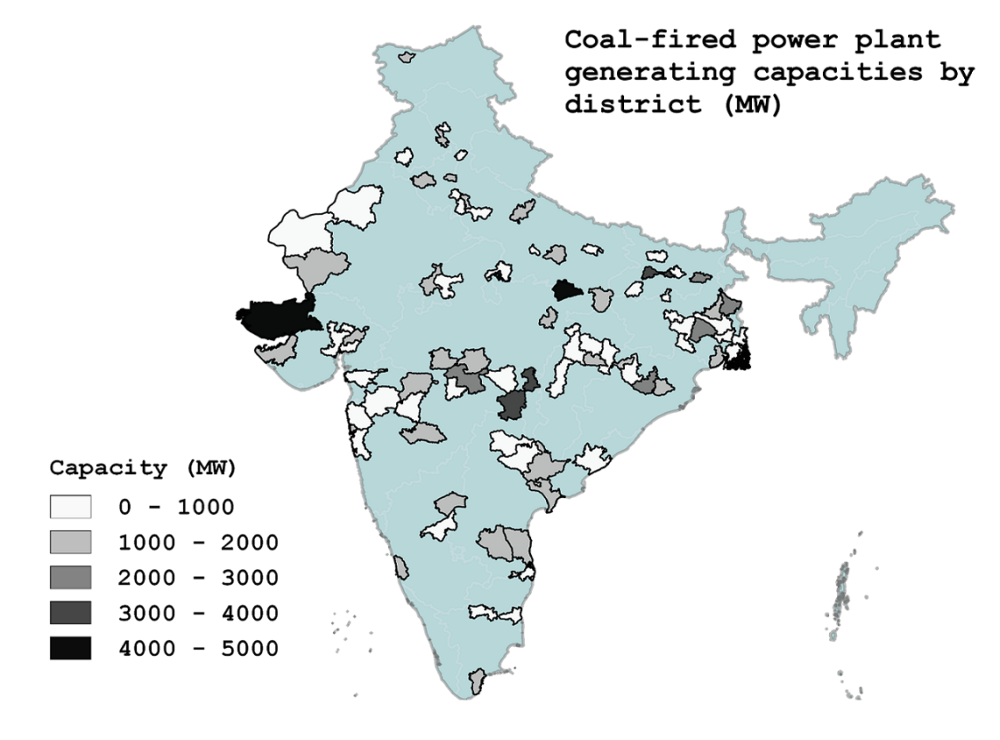

The current situation in India is a timely example of how well-intentioned US policies may be missing an opportunity to help facilitate immediate gains in CO2 reduction. Nearly 300 million people lack access to reliable electricity in India. The government has announced an ambitious plan to definitively provide electricity access to the remaining 70 million households by 2019. To power its growth, India plans to double its coal production to 1.5 billion tons by 2020. Unfortunately for the climate, India has some of the least-efficient coal-fired power plants in the world. And though India plans to source up to 40 percent of its electricity from renewables by 2030, coal still looms large in India’s long-term as well as near-term energy future.

India’s changing coal sector

India’s coal sector has long been the object of power politics. Coal India Limited (CIL), a state-owned enterprise, is the largest producer of coal not only in the country, but in the world. Through negotiations between the government and CIL, national coal prices have been subsidized below global market value, incentivizing electricity companies and others to consume coal inefficiently.

In 2012, India’s Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), determined that—instead of employing a competitive bidding process (in which the Prime Minister agreed to engage in 2004)—the government corruptly awarded 216 coal blocks to companies from 2004 to 2010. Termed the “Coalgate” scandal, the initial auctioning process cost the Indian government an estimated USD $33 billion in potential revenue. This led to the Supreme Court’s cancellation of more than 200 illegal coal block awards made over the past two decades. Add to this a vicious cycle of subsidies or free electricity to placate various segments of India’s diverse electorate and you have an ecosystem in which the electricity generation and distribution infrastructure are terribly strained. It came as no surprise that India suffered a major blackout in July 2012 that left 600 million people in the dark.

More recently, India’s coal sector has started to turn things around with faster approvals of coal block allocations, tighter production oversight (including a website to track progress at mines), and greater transparency and revenue sharing with local communities (as discussed by CGD colleagues previously). Additionally, power plants are finally stocked with enough coal to meet peak electricity demand. In addition, as a result of record coal production by CIL, India’s coal imports dropped 19 percent between May 2014 and May 2015. In response to rising production, Power Minister Piyush Goyal stated earlier this year that India plans to stop imports of coal for thermal power in the next two to three years.

Helping India clean up its coal

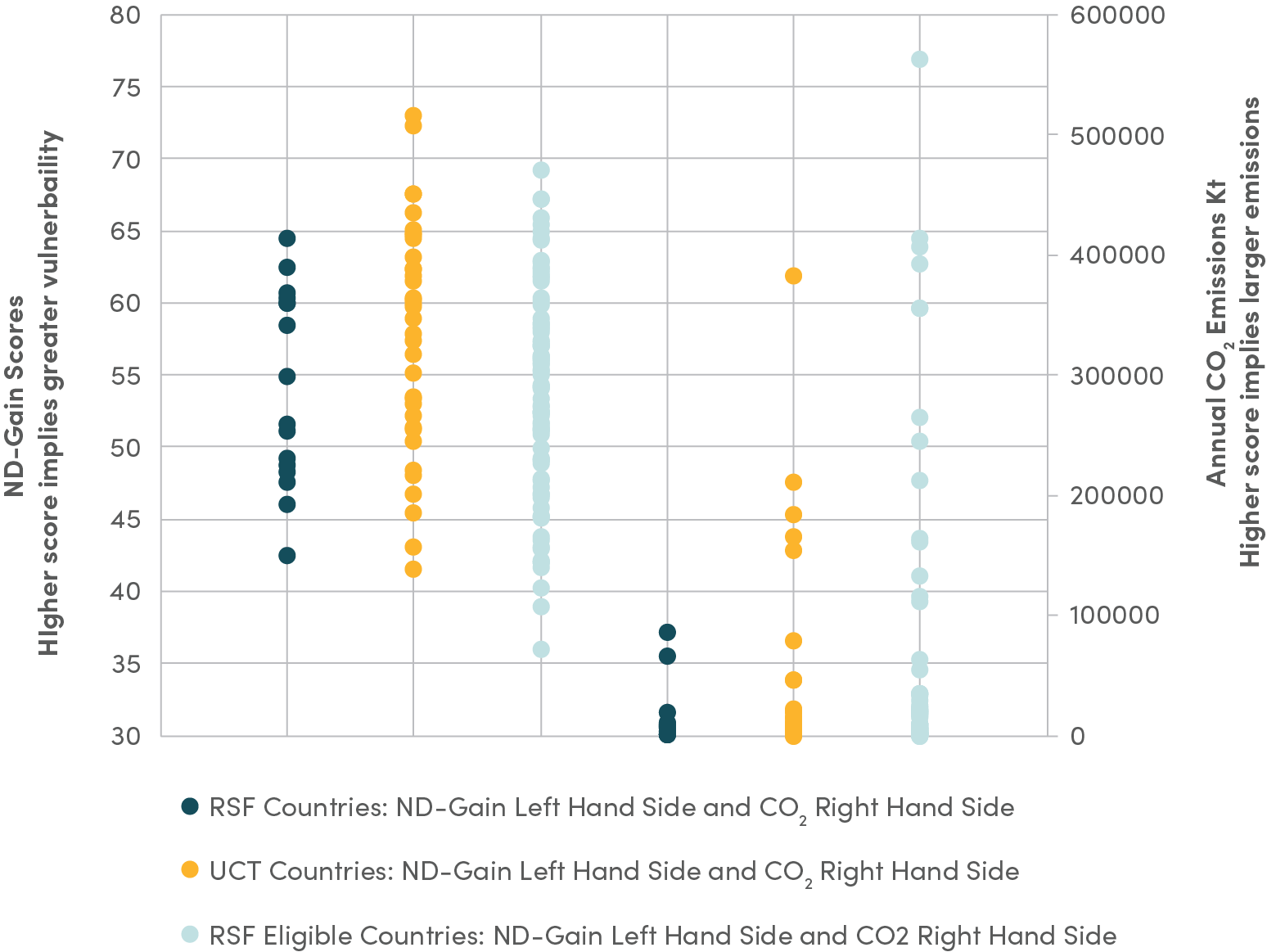

Given the overhaul of India’s coal sector, the timing is right to help India clean up its coal. According to the IEA, achieving greater efficiency in India’s coal-fired power generation (currently only 26 percent efficient) is inhibited by high temperatures, limited water supplies, and poor quality coal. Analysis conducted by the US Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) on “off-the-shelf” technologies to improve thermal power plant efficiency suggests that existing power plants could see significant emissions reductions with payback periods from the technologies ranging from “one to seven years depending on the level of efficiency achieved.” India stands to gain the most from such investments. According to Ecofys, the CO2 intensity for fossil-fired power generation for India is 1,174 g/kWh and has a reduction potential of 43 percent from current levels through public power generation. This is the highest reduction potential of any country analyzed in the report. Since India plans to continue using coal until at least 2050, it needs partners that can help it reduce emissions from this sector immediately.

|

|

|

|

European Union |

|

Indo-EU Working Group on Coal and Clean-Coal Technologies working on deployment of sustainable mining technologies |

|

United States |

|

NETL–NTPC MoU on technical assistance on coal efficiency including information exchange on carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) |

|

Australia |

|

Recent creation of the Australia–India Joint Research Center for coal and energy technology with a focus on clean coal technologies. Existing cooperation to mitigate and utilize ventilation air methane in India |

|

Japan |

|

Joint statement between two countries states Japan's agreement to support the introduction of high-efficiency coal-fired power generation in India. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) indicates willingness to finance such projects |

|

Poland |

|

Cooperation on development of clean coal technologies like washing of coal and Coalbed methane, coal mine methane, ventilation-air methane, and underground coal gasification |

One of the United States’ great strengths as a leader in scientific and technological innovation is a network of national laboratories that conduct research and help develop and establish emerging technologies. Many of these national labs have also collaborated with other countries to provide technical assistance on a variety of energy projects. Recently, NETL signed a long-pending memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the research arm of India’s NTPC (formerly the National Thermal Power Corporation). The aim of this MOU is to “help India reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired electricity generation” through—among many things—information exchange on carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS).

However, the United States should go a step further by providing technical assistance to deploy readymade clean coal technologies to help India realize immediate gains through CO2 reductions. USAID has a long history of working on coal efficiency improvements in India. Unfortunately, these programs were halted in 2011. If restarted, such programs could abate over 100 million tons of CO2 per year. The gains are significant and the argument is clear: investing in the greening of India’s coal sector would help mitigate the worst impacts of climate change.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.