Recommended

POLICY PAPERS

Last month, thousands of family planning policymakers, practitioners, researchers, advocates, and funders gathered in Pattaya City, Thailand for four days of learning and exchanging. The conference plenaries centered on the broad importance of family planning in achieving universal health coverage (UHC). Research presentations and panel discussions helped the community move closer to fleshing out what “FP for UHC” should mean in practice. Here are my reflections on three specific areas of the #FPforAll agenda, linking to prior CGD research on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) financing.

1. Channeling more aid through governments

Large amounts of external aid for health continue to be spent on fragmented, off-budget programs outside of government coffers. This creates challenges for governments that seek to strengthen national systems, develop a clear picture of the results that programs achieve, and mobilize sustainable resources for the most effective uses. Family planning is no exception; services are often organized and delivered through vertical programs with dedicated funds that rely heavily on donors and NGOs, plus out of pocket payments, intensifying risks from aid volatility and economic downturns (discussed more below). Many International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP) sessions examined the current family planning financing landscape, including donor rankings and trends, new commitments to increase domestic budget allocations, and global and national expenditure estimates.

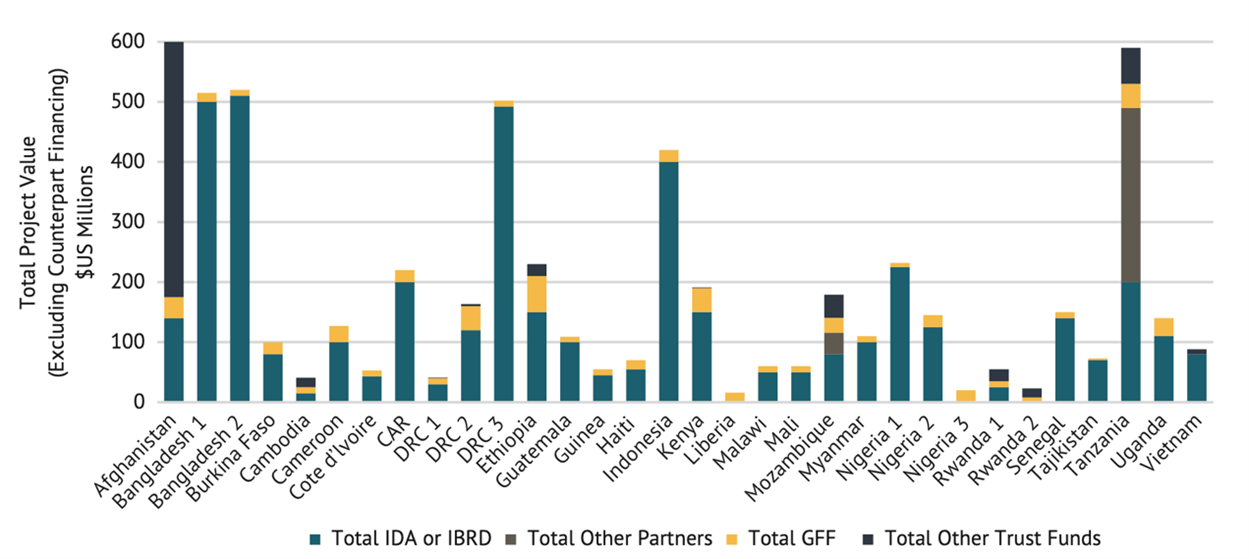

The Global Financing Facility (GFF) is a relatively new partnership (launched in 2015), backed by a multi-donor World Bank Trust Fund, that seeks to strengthen country ownership, health financing and UHC reforms, domestic contributions, and donor coordination for SRH and other health services. CGD’s work on the GFF, which I presented at ICFP, found that the GFF directs additional funding to government budgets via increased World Bank lending for health, helping to reduce SRH funding gaps. The GFF thus represents an important value-add within the broader family planning and global health architecture, where support from other donors continues to be spent mostly outside of country systems. But the GFF’s role in prioritizing resources behind a set of SRH services within a specific funding envelope remains less clear, underscoring the challenges of working through country systems and aligning multiple external partners around a unified set of priorities.

On the whole, aid agencies and philanthropies should be enabling more integration with country systems as part of their commitment to shift power, including proactive coordination among donors, enhanced spending efficiency, and reform for cross-cutting functions like procurement and supply chain. Relatedly, the FP2030 Partnership now seeks to further advance commitments, accountability, measurement, and coordination among governments, donors, and NGOs in a larger set of 83 countries—bolstered by a new first-time investment from USAID.

2. Integrating contraception in health benefits packages

Including contraception in health benefits packages (HBP) and national health insurance schemes is one way to help shift toward more integration with UHC systems. The why and how of such inclusion was the topic of a panel I spoke on, drawing from CGD research by me and Rachel Silverman, alongside panelists from MSI Reproductive Choices, Options Consultancy Services, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, who reflected on country-specific experiences in Ghana and Nigeria.

A takeaway was that in many countries, at some point in their long-lasting UHC journeys, including family planning in HBPs and insurance schemes can be a key move for sustainability, country ownership, and contraceptive access, especially considering the likely cost-savings, economic progress, and climate benefits that come from expanded contraceptive provision.

But integrating contraception in HBPs is easier said than done. When health financing officials use health technology assessment and related economic evaluation to consider the costs and benefits of contraception, it can be hard for them to understand and weigh the value of method choice. For instance, long-acting methods are more effective at preventing pregnancy and generally more cost-effective than other reversible methods, but expanding method availability overall is known to increase contraceptive use. Further, many countries have nascent UHC policies and insurance systems with limited population reach, which hinders the actual impact of inclusion.

3. Advancing quality, affordability, and access in the private sector amid current economic shocks

Private facilities, retail pharmacies, and drug shops—where women and girls are typically required to pay out-of-pocket (OOP) from their household incomes—are a common family planning access point. OOP expenditures for contraceptives in the private sector are substantial; a recent analysis tallies them at $2.73 billion across 132 low- and middle-income countries, with significant variation in prices and quality across providers. Even in countries where a full range of contraceptive methods are included in public programs and insurance schemes, OOP payments remain common; users may still incur expenses to cover transport, registration and consultation fees, and the cost of supplies in the event of stockouts.

Considering the private sector’s (complex) importance to current and future family planning access, a plethora of sessions—and an entire pre-conference—focused on the topic. A handful of new organizations and initiatives that focus specifically on healthy SRH markets made their ICFP debut, sharing new plans to improve the role of the private sector within the family planning agenda. USAID’s Frontier Health Markets (FHM) Engage program and SEMA Reproductive Health both seek to identify the root causes of underperforming markets and collaboratively design new strategies with local and global partners to address them.

Notably, women and girls may face barriers in the private sector that preclude them from accessing contraception, with potential consequences for equity, method choice, and product quality. In light of the global financial crisis and increased fiscal pressures, many countries are unlikely to increase—or even maintain—current levels of health spending, meaning that private provision and OOP payments for contraception may become more dominant in some contexts. Indeed, just this week, Ghana suspended payments on most of its external debt amid the worsening economic crisis. And the latest Family Planning Market Report, launched earlier in December, shows that the public-sector contraceptive market value contracted by 8 percent from 2020 to 2021, in large part due to decreased donor funding.

This makes it even more important for family planning donors to carefully plan and coordinate with governments and other development partners when making decisions to drawdown support or implement co-financing requirements. The family planning community, including new groups like FHM Engage and SEMA, must help keep tabs on the downstream effects of economic shocks on OOP payments for contraception and related implications for equity, method, quality, and financial hardship. Without reducing financial barriers, especially those placed on poor and vulnerable groups, the family planning community could fall short of its goal to achieve sustainable and equitable access for all.

This blog barely scratches the surface of all ICFP had to offer, ranging from deep dives into digital platforms and innovations in male contraceptives, to a new INGO initiative on more equitable operating models and concrete ways to learn from both exemplar experiences and program failures—a longtime CGD interest. For further learning and discussion, watch the ICFP session recordings online and stay tuned for more CGD work on family planning and gender equality and inclusion next year.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.