Recommended

Blog Post

Blog Post

The administration's FY24 international affairs budget request was always going to face long odds on Capitol Hill, where Republicans took control of the House pledging to curb spending. But rather than pare back, the White House released an ambitious budget aimed at tackling a wide range of challenges facing countries worldwide and reasserting US leadership, particularly in strategic areas where the administration hopes to displace China's growing global influence. In addition to formally kicking off the annual budget and appropriations process, the president's budget request offers new insight into the administration's priorities, which are many.

Here's a quick look at what stood out from our read (featuring interactive charts).

Mobilize more through multilaterals

The budget for Treasury's international programs reflects greater ambition than in recent years, if not prioritization, on the part of the administration. The administration highlights the roles international financial institutions have played in recent years, helping countries stave off more dire consequences amid compounding crises.

In making the case for $2.293 billion in support for multilateral development banks (MDBs), the budget documents underscore how US investments in MDBs benefit from additional leverage and can spur increased contributions from other shareholders. Of course, Treasury also acknowledges its push to see these institutions evolve. (For more on these reform efforts, from CGD voices and other leading experts—including our partner think tanks in Morocco, India, Ghana, and Brazil— check out our new MDB Reform Accelerator.)

In addition to meeting existing pledges and commitments, the budget seeks $26.8 million for World Bank International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) loan guarantees to support energy investments in South and Southeast Asia along with additional funding to support the World Bank's concessional arm, the International Development Association (IDA), the Asian Development Fund (AsDF), and the African Development Fund (AfDF) through payments toward outstanding US arrears. The administration is also requesting $75 million for an initial subscription to a capital increase at the Inter-American Investment Corporation, better known as IDB Invest, the private sector lending window of the Inter-American Development Bank. The largest shareholder in both the IDB and IDB Invest, the United States had previously requested reforms before making a new capital commitment—the decision to move forward is a sign of its satisfaction with the progress made by the institution. Finally, the request includes new funding for two Asian Development Bank initiatives focused on energy investments and emissions reduction.

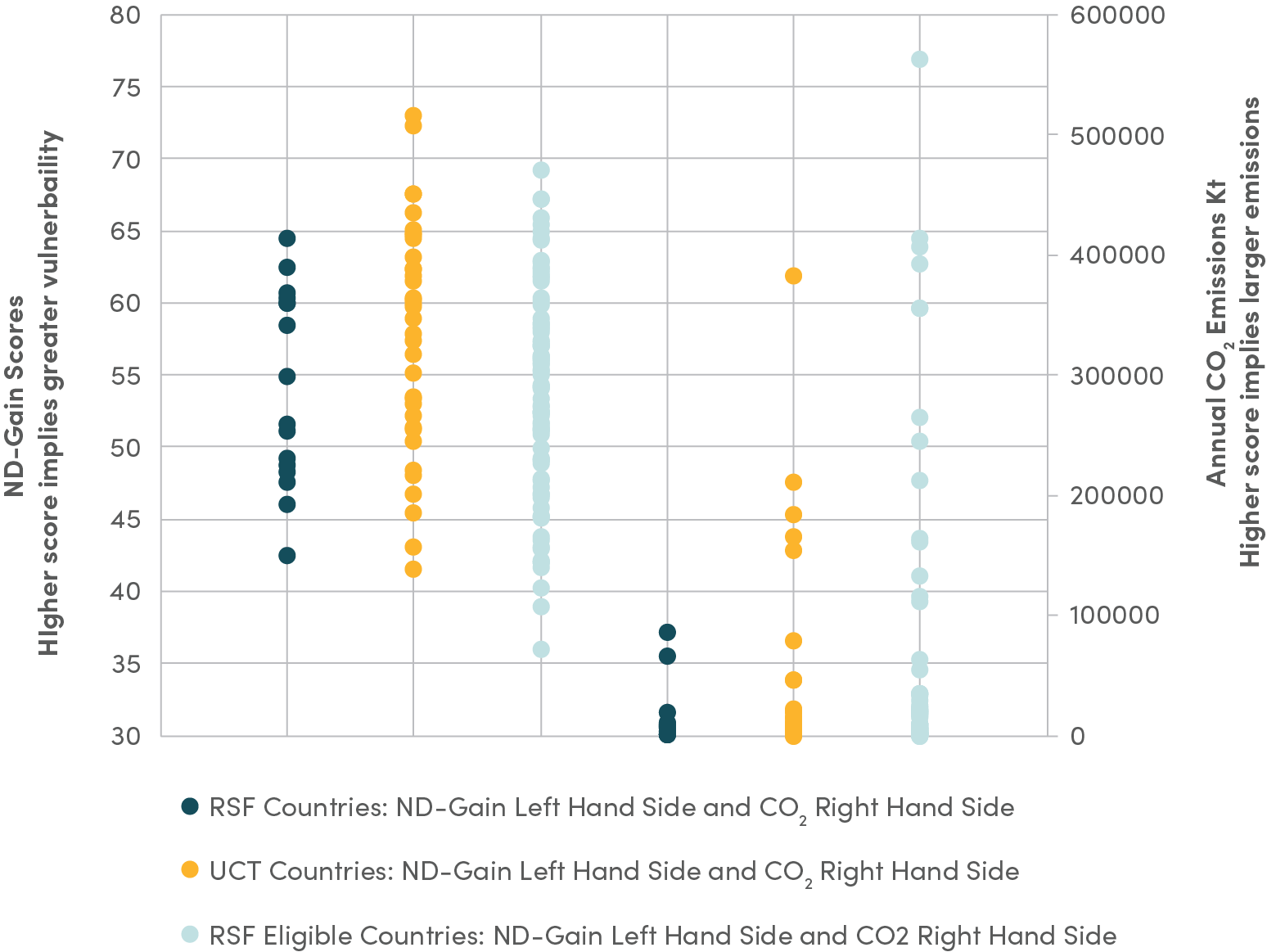

And still aiming to deliver on big climate financing commitments, the administration is again requesting $1.6 billion for the Green Climate Fund—this time with half of the funds channeled through the State Department and the other half through Treasury. The request also includes a slightly scaled-back request for a loan to the Clean Technology Fund (one of two Climate Investment Funds) and resources to deliver a second payment toward its most recent Global Environment Facility pledge. Three of our CGD colleagues, Nancy Lee, Clemence Landers, and Samuel Matthews, recently conducted a deep dive into these major climate funds. Their newly published report identifies challenges in some of these funds' performance and funding allocation (including targeting financing to meet needs for both mitigation and adaptation). They recommend donors avoid any further fragmentation of the system and consider consolidation—or at least prioritize fund performance in deciding where to put additional resources.

With food insecurity still a pressing challenge in many parts of the world, the administration hopes to provide additional support to the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), including a $35 million contribution to its Enhanced Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme (ASAP+), and the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program (GAFSP). The request further includes a contribution to the World Bank's Global Infrastructure Facility and two Resilient Development Trust Funds that provide financing for adaptation and preparing and recovering from natural disasters.

Continuing investment in global health

Global health funding would remain near level under the administration's request with an increase in funding channeled through the State Department and a reduction in funds managed by USAID. More than $1.2 billion is tagged for global health security—of which $500 million will comprise a contribution to the Pandemic Fund.

Still short of its capitalization goal, continued resources and leadership from the US will be important to ensure the new fund can provide financing for low- and middle-income-countries that will enable high-impact investments to stave off future global health threats. According to a recent Reuters story, expressed interest from low- and middle-income countries vastly exceeds currently available resources at the fund.

The request also includes what could be first-time funding for a new Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy at the Department of State. Still awaiting congressional sign-off, the bureau would bring PEPFAR, an existing Office of International Health and Biodefense, and the Coordinator for Global COVID-19 Response, under the same proverbial roof—with Dr. John Nkengasong at the helm. The State Department hopes a new bureau will elevate global health security and improve coordination. However, it's not yet clear how the proposed changes would interact with pandemic preparedness provisions passed as part of last year's defense authorization. And some observers have voiced concern that significant organizational shifts could undermine PEPFAR's unique advantages.

Rebuilding base humanitarian funding

With humanitarian needs projected to reach record highs in 2023, the administration is requesting modest additional resources for key accounts that provide urgent support in response to crises. Over the last few years, even as the US has scaled up humanitarian support, much of that funding has been provided outside of the base budget through emergency supplemental spending. In a bid to ensure these accounts don't get shorted, the administration's budget documents provide adjusted FY23 appropriations figures capturing recent aid provided in response to Russia's ongoing war with Ukraine to meet humanitarian needs outside of Ukraine's borders.

Boosting bilateral economic assistance

The budget request includes increases for Development Assistance (DA) and the Economic Support Fund (ESF)—core bilateral accounts that support a wide range of activities, from promoting resilient growth and tackling energy poverty to strengthening democratic institutions and bolstering food security.

From a regional standpoint, the largest resource boosts are envisioned to support activities in East Asia and the Pacific—where China's presence is a particular worry; Africa—to help deliver on commitments made at December's US-Africa Leaders Summit; and the Western Hemisphere—amid concerns about governance, forced displacement, and irregular migration.

Africa

Coming on the heels of the December summit, the budget touts $8 billion for foreign assistance across sub-Saharan Africa—of which $1.84 billion is Development Assistance, an increase of $215 million over last year's request—with continued funding for Power Africa and Prosper Africa, and new funding for the President's Digital Transformation with Africa initiative.

Digging into the numbers, it's evident a few African countries would see significant boosts in DA compared to FY21 (the most recent year for which country-specific data is available), while others would see far more modest increases and even level funding. And the majority of US support to sub-Saharan Africa continues to be provided through global health programs.

Still, the administration has shown other signs of its continued interest in the region, including a series of visits from high-profile officials. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen traveled to Senegal, Zambia, and South Africa early in the year. First Lady Jill Biden embarked on a diplomatic trip to Kenya and Namibia the following month. Secretary of State Antony Blinken returns to the continent this week, and Vice President Kamala Harris's upcoming travel plans include stops in Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia.

Western Hemisphere

The administration would allocate $40 million from ESF for a contribution to the Global Concessional Financing Facility (GCFF), a World Bank trust fund that provides middle-income countries hosting large refugee populations with access to loans on more concessional terms. To date, two countries in the Western Hemisphere are eligible for, and have benefitted from, GCFF support: Colombia and Ecuador.

Colombia has been the leading destination for Venezuelans fleeing that country's political crisis. With the right policies, those Venezuelan migrants can be a boon to Colombia's economy and those of other host countries. But ensuring those hosts have resources and policies to support robust integration will be critical. Contributions from donors like the US are what allow the GCFF to provide lending on concessional terms, helping to incentivize best practices that yield benefits for both host communities and migrants.

Asking for $1 billion for MCC

It's been well over a decade since MCC's budget topped a billion dollars—but the administration's request would put them back at 10 figures. Funding is expected to support new compacts with Belize and Sierra Leone, and a regional compact with Côte d'Ivoire focused on energy.

Ahead of its 20-year anniversary, the agency continues to seek expansion of its current candidate pool—a change that would require congressional action. As countries have (happily) grown wealthier over the last two decades, the number classified as low- and lower-middle-income has grown smaller. MCC's latest proposal would draw a new income cut-off at the level of the IBRD's graduation threshold, which was $7,155 per capita in FY22.

Providing steady resources for DFC

After receiving a big boost in funding last year, the budget includes just a modest increase in administrative expenses for the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). The more significant proposed change comes in an ask for new mandatory spending (see below).

Out-competing China?

For the second year running, the administration's request for the Department of State and Foreign Operations proposes new mandatory funding. While last year's ask—which centered on investments in pandemic preparedness—failed to gain traction, the latest pitch focuses on competition with China.

Shared concern over China's growing global influence may well be where the administration and lawmakers are most in sync. It's under an "Out-Compete China" banner that the White House is seeking $2 billion to capitalize a revolving fund that would support equity investments made by DFC. Congress gave DFC the authority to make direct equity investments, but illogical budget treatment has limited its use and continues to place needless pressure on the international affairs account. Despite actors on all sides broadly acknowledging that current practice for scoring direct equity is less than ideal, a fix has remained elusive. The creation of a revolving fund—which has plenty of precedent across the federal government—is a practical workaround. After an initial capitalization, the revolving fund would be self-sustaining thanks to returns from DFC's equity investments. But it will be important that the upfront cost doesn't come at the expense of other critical development and humanitarian priorities—hence the effort to secure mandatory funding that won't count against a discretionary topline. New mandatory funding will always be an enormous lift on Capitol Hill. But if any subject could bring together hardened partisans, this is probably in contention. And even with an uphill battle ahead, it's encouraging to see the administration put forward a solution.

In addition, at least $200 million from the mandatory pot would be transferred to MCC for investments in infrastructure—where the agency boasts nearly 20 years of experience.

More broadly, the administration’s decision to pursue new mandatory funding within the 150 account is an interesting innovation. Congressional oversight is important, and yet the slow and fickle annual appropriations process (sometimes relying on multiple continuing resolutions) can be frustrating. Still, while, in some instances there’s a strong case to be made for multi-year investments (which can be hard to secure and protect from rescission) a more cynical take might be that a request for mandatory spending allows the administration to signal support without having to go as far as making a direct trade-off. In the absence of a discretionary topline escape hatch like the Overseas Contingency Operations designation, it will be interesting to see if this remains a rare pitch or a more regular fixture.

Strengthening USAID’s operational capacity

USAID Administrator Samantha Power has made no secret of her interest in strengthening the agency's workforce. A recently published (long-awaited) Acquisitions & Assistance strategy heavily emphasizes the need to bolster contracting and agreement officers—in number and skill. Correspondingly, the budget seeks to shore up USAID's operating expenses.

Glimpsing USAID reorganization

During the Trump administration, under Administrator Mark Green, USAID undertook a "transformation" effort that yielded—among other things—several changes to the agency organogram. Last year, USAID began socializing a few additional shifts. The new congressional budget justification offers a glimpse—albeit an incomplete one—at these changes through funding allocation changes via the Development Assistance and Economic Support Fund. A new Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance (DRG) is the most sizable of these changes. But in addition, agency leadership proposed moving existing environment programs from the broadly-tasked Bureau for Development, Democracy, and Innovation (DDI) to the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security (RFS) and tweaking its name to reflect the change. Finally, picking up a thread from the previous administration—which had sought to consolidate and better align agency policy, performance, and budget—current leadership advanced a more modest merger of USAID's Bureau for Policy, Planning and Learning (PPL) with the Office of Budget and Resource Management (BRM). If the shift leaves USAID positioned to integrate evidence in more of its decision-making processes, we'll commit to learning a new acronym (PLR - Bureau for Policy, Learning, and Resource Management).

Finally, the FY24 request includes $7 million in new dedicated funding for the recently established USAID Office of the Chief Economist. We've been excited about the prospect of an elevated, empowered chief economist at the agency—and are eager to see how the office will support increased use (and generation) of cost-effectiveness evidence at the world's largest bilateral aid agency.

We'll look forward to learning more about proposed FY24 development and humanitarian spending—and more about the congressional receptivity—during budget hearings in the coming weeks.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock