Recommended

WORKING PAPERS

Forecasts of the future shape of the global economy, if they are at least somewhat accurate, can help planning and policy discussions in areas from global governance through business expansion plans. At the same time, this relies on forecasts in fact being somewhat accurate, and it’s a cliché that predicting things is hard, especially about the future. To allow for that uncertainty, in a new paper, Zack Gehan and I come up with a set of potential scenarios about the future using a reasonably simple approach. Results that hold across those scenarios are (we hope) more robust to uncertainty about the future.

We generate our central forecast using two inputs: the coefficients from a regression analysis of the historical links between growth, demographic factors, education, and national temperature; and forecasts of those variables to 2050. And we create a plausible range of outcomes using the error terms from that regression to create low and high scenarios for groups of countries. It’s a process that shares some features with the one used to create the five ‘SSPs,’ the shared socioeconomic pathway scenarios that underpin some of the modeling around the extent and impact of climate change. (Although one difference: unlike the SSPs, we try to take into account at least some of the impact of climate change on future economic prospects).

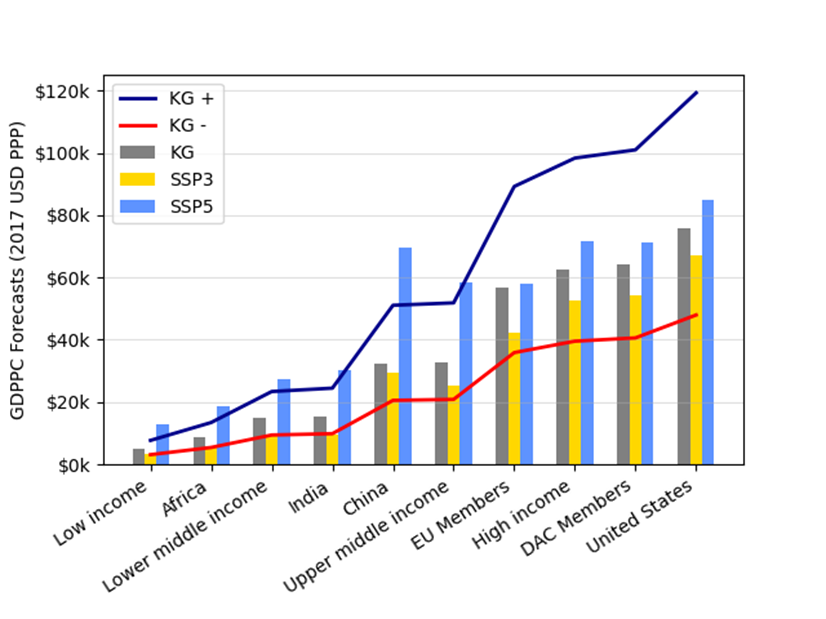

Our central forecast matches most closely the SSP called “Middle of the Road,” perhaps both reassuring and unsurprising. Our range for global GDP per capita in 2050 is between $16-39,000, and the range for the SSPs is $18-42,000 (current global GDP per capita is around $16,000). For what it is worth, that suggests to us that the SSPs do present a range of potential economic outcomes that seems reasonable –noting again that, because we followed a somewhat similar approach to forecasting, this is hardly an utterly independent verification. The figure below presents our central forecast (KG) and range (KG+ and KG-) along with the most ‘extreme’ SSP scenarios in terms of global GDP per capita outcomes: SSP3, titled “Regional Rivalry (A Rocky Road)” and SSP5, titled “Fossil-fueled Development (Taking the Highway).”

It is no challenge to think of events that could leave the world looking far different from any of the scenarios we work with. Even within the scenarios, the range of outcomes is large enough to suggest it is very plausible current global income convergence could dramatically accelerate or it could reverse, for example. The impact of policy change at the national and global level could be very large. That said, some conclusions look to be reasonably robust at least across the range of scenarios:

-

Demographic change will be an increasing drag on growth particularly in richer (upper middle- and high-income) countries. Education is likely to be a factor favoring convergence globally (because average years of schooling will grow faster in poorer countries). And while climate change (at least as reflected in temperature, at the national level) will be a force for slower growth especially in poorer countries, it is unlikely to be a major driver of global economic trends up to 2050.

-

The share of OECD DAC (traditional donor) countries in the global economy is very likely to shrink. This reflects the likelihood of (i) relatively slower per capita income growth (both compared to the past and to poorer countries); and (ii) stalling or declining population compared to continued population growth in most low- and middle-income countries.

-

It is plausible to imagine that $2.15 a day poverty will have effectively disappeared by 2050 (which would be good news, if two decades later than envisaged by the UN Sustainable Development Goals). It is also plausible that more than two thirds of the world will be living on more than $10 a day (up from about 42 percent today). Low income countries may disappear as a group, and the proportion of the world living in high income countries is very likely to more than double from its current proportion of 16 percent.

-

The shrinking share of the US in the global economy suggests an end to the country’s veto power in both IMF and World Bank decision-making processes unless those institutions move even further away from a voting/shareholding formula based on relative economic size.

-

Global electricity consumption can be reasonably expected to double by 2050. While high-income countries will see slow consumption growth, current low-income countries will still be responsible for less than five percent of electricity consumption (more likely two percent) in 2050.

-

The US is likely to remain the largest military in terms of spending in 2050, but its global lead will considerably diminish, and it is plausible to imagine both India and China outspending the US on defense in 2050.

For all of the challenges this likely future may present, it is one of a richer planet with more resources to respond to threat from pandemics through climate shocks, containing many fewer people living in the kind of absolute poverty that was the lot of ninety percent of humankind for nearly all of our history.

Los pronósticos para conocer el estado de la economía global, si son al menos algo precisos, pueden ayudar a la planificación y las discusiones de políticas en áreas que van desde la gobernanza global hasta los planes de expansión comercial. Al mismo tiempo, esto depende de que las proyecciones sean, de hecho, algo precisas, y es un cliché que predecir cosas es difícil, especialmente sobre el futuro. Para permitir esa incertidumbre, en un nuevo artículo, Zack Gehan y yo presentamos un conjunto de posibles escenarios sobre el futuro utilizando un enfoque razonablemente simple. Los resultados que se mantienen en esos escenarios son (esperamos) más robustos ante la incertidumbre sobre el futuro.

Generamos nuestro pronóstico central utilizando dos insumos: los coeficientes de un análisis de regresión de los vínculos históricos entre el crecimiento, los factores demográficos, la educación y la temperatura nacional; y pronósticos de esas variables para 2050. Y creamos un rango plausible de resultados usando los términos de error de esa regresión para crear escenarios superiores e inferiores para grupos de países. Es un proceso que comparte algunas características con el que se usó para crear los cinco "SSP", los escenarios de vías socioeconómicas compartidas que sustentan algunos de los modelos sobre el alcance y el impacto del cambio climático. (Aunque, a diferencia de los SSP, tratamos de tener en cuenta al menos parte del impacto del cambio climático en las perspectivas económicas futuras).

Nuestro pronóstico central coincide más estrechamente con el SSP llamado "Mitad del camino", quizás un tanto tranquilizador como un poco sorprendente. Nuestro rango para el PIB global per cápita en 2050 es de entre $16 y 39 000, y el rango para los SSP es de $18-42 000 (el PIB global actual per cápita es de alrededor de $16 000). Por si sirve de algo, eso nos sugiere que los SSP sí presentan un rango de posibles resultados económicos que parecen razonables, señalando de nuevo que, debido a que seguimos un enfoque algo similar para el pronóstico, esto difícilmente es una verificación completamente independiente. La siguiente figura presenta nuestro pronóstico central (KG) y rango (KG+ y KG-) junto con los escenarios SSP más 'extremos' en términos de resultados del PIB per cápita global: SSP3, titulado "Rivalidad regional (un camino rocoso)" y SSP5 , titulado “Desarrollo alimentado por combustibles fósiles (tomando la carretera)”.

No es difícil imaginar eventos que podrían hacer que el mundo se vea muy diferente a cualquiera de los escenarios con los que trabajamos. Incluso dentro de los escenarios, el rango de resultados es lo suficientemente amplio como para sugerir que es muy plausible que la convergencia de ingresos globales actuales pueda acelerarse dramáticamente o revertirse, por ejemplo. El impacto del cambio de políticas a nivel nacional y global podría ser muy grande. Dicho esto, algunas conclusiones parecen ser razonablemente sólidas al menos en el rango de escenarios:

- El cambio demográfico será una traba cada vez mayor para el crecimiento, especialmente en países ricos (de ingresos medios-altos y altos). Es probable que la educación sea un factor que favorezca la convergencia global (ya que el número promedio de años de escolarización crecerá más rápido en los países más pobres). Si bien el cambio climático (al menos en lo que respecta a la temperatura a nivel nacional) será un factor para un crecimiento más lento, especialmente en los países más pobres, es poco probable que sea un factor determinante de las tendencias económicas globales hasta 2050.

- Es muy probable que la participación de los países miembros del Comité de Ayuda al Desarrollo de la OCDE (donantes tradicionales) en la economía mundial disminuya. Esto se debe a la probabilidad de un crecimiento per cápita relativamente más lento (tanto en comparación con el pasado como con los países más pobres) y a una población que se estanca o disminuye en comparación con el crecimiento continuo de la población en la mayoría de los países de ingresos bajos y medios.

- Es plausible imaginar que la pobreza de $2.15 al día habrá desaparecido efectivamente para el 2050 (lo que sería una buena noticia, aunque dos décadas más tarde de lo previsto en los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible de las Naciones Unidas). También es plausible que más de dos tercios del mundo vivirán con más de $10 al día (un aumento desde el actual 42 por ciento). Los países de bajos ingresos podrían desaparecer como grupo, y es muy probable que la proporción de personas que viven en países de altos ingresos se duplique desde su proporción actual del 16 por ciento.

- La disminución de la participación de los Estados Unidos en la economía global sugiere el fin del poder de veto del país en los procesos de toma de decisiones tanto del FMI como del Banco Mundial, a menos que estas instituciones se alejen aún más de una fórmula de votación/participación basada en el tamaño económico relativo.

- Se espera que el consumo global de electricidad se duplique para 2050. Mientras que los países de ingresos altos verán un crecimiento lento del consumo, es probable que los países de ingresos bajos actuales sean responsables de menos del cinco por ciento del consumo de electricidad (más probablemente del dos por ciento) en 2050.

- Es probable que Estados Unidos siga siendo el país que más gasta en defensa en 2050, pero su ventaja global disminuirá considerablemente, y es plausible imaginar que tanto India como China gasten más que Estados Unidos en defensa en 2050.

A pesar de los desafíos que pueda presentar este futuro probable, se trata de un planeta más rico con más recursos para responder a las amenazas de pandemias y choques climáticos y con muchas menos personas viviendo en la pobreza absoluta que fue la suerte del noventa por ciento de la humanidad durante casi toda nuestra historia.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock