Recommended

Introduction

In response to the far-reaching impact of the COVID-19 crisis, governments worldwide ramped up spending in the health sector. However, deteriorating macroeconomic conditions—alongside consequences of the war in Ukraine and competing national priorities—will significantly constrain public and aid spending on health in 2023 and beyond.

As countries face high debt burdens and mounting pressure from inflation, gaps between needs and spending in the health sector are likely to widen further. Health systems in many countries are still reeling from the fallout of the pandemic. Notably, levels of excess mortality remain high across low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), despite some evidence of endemicity of COVID-19.[1] Further, the combination of postponed or foregone healthcare, aging populations, high levels of health risk factors, and the burden of long COVID require not only more resources for recurrent health expenditures, but also more investment in capital.[2]

Yet, the concerning reality is that many LMICs—where unmet health needs are largest—are projected to see health spending drop or plateau, jeopardizing the path to managing ongoing risks and working towards post-COVID recovery and universal health coverage. A World Bank report estimates that 41 governments will spend less on health between now and 2027 than they did in the pre-pandemic period; in 69 countries, spending will remain almost on par with pre-pandemic levels. Consequently, available resources will amount to a fraction of what is needed for health systems to sustain essential services, recover lost ground due to COVID-related disruptions, and adequately prepare for future pandemic risks.

The global economic downturn is also squeezing aid budgets, even while external assistance is urgently needed to support LMICs. For instance, the United Kingdom’s aid budget could be cut for the third time in three years, and the government’s contribution to the International Development Association (IDA), the World Bank’s concessional financing window and a major funder of health systems, was cut in half in 2021. And new government leadership in Sweden, long-known as a champion of development assistance, recently announced cuts to its aid budget, falling below its previous target of one percent of GNI.

Worsening macroeconomic conditions will likely also impact countries’ abilities to meet co-financing requirements for HIV and immunization programs, among other health services. Projected aid transition timelines may, in turn, be affected as countries remain and/or revert to low-income or lower-middle-income status, further stretching finite donor resources.

At the same time, global challenges like climate change, unprecedented levels of food insecurity, and reconstruction in Ukraine are creating additional long-term imperatives for development finance. Against this backdrop, the prevailing development finance architecture is being revisited, with ideas proposed to expand financing—both volumes and instruments—to meet urgent global challenges. For instance, last fall, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) established the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, a new instrument to support eligible countries to respond to long-term structural challenges to resilience, including climate change but also pandemic risks. A roadmap to reform the World Bank’s operating model and expand its lending capacity is also currently under development. Assuring that health is sufficiently prioritized within this agenda is essential—especially as COVID-19 falls further down the list of policymakers’ concerns.

This CGD note summarizes the implications of the macroeconomic context and broader financing outlook for domestic and external health spending and proposes a “menu” of policy options to keep health spending on track and blunt negative impacts on health systems and population health around the world. It draws on findings from recent research and a private roundtable discussion (under Chatham House rules) with leading health and finance experts, convened by CGD in October 2022.

Outlook for public spending on health

A recent body of research published by the World Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), World Health Organization (WHO), and CGD examines trends in health spending before and during the pandemic—and highlights projections for the future. Taken together, these findings paint a bleak picture of health spending levels across countries. Below, we distill four key takeaways.

1. During the pandemic, government health spending increased in almost all low-income and lower-middle-income countries—but so did spending on everything else

Countries mounted an unprecedented increase in health spending in response to the COVID crisis. Almost all low-income and lower-middle income countries increased government spending on health in 2020, both in per capita terms and as a share of GDP.

Notably, however, spending levels varied across countries. Public spending on health increased more in advanced economies compared to low-income and lower-middle-income countries. On average, OECD governments committed between 0.6-2.5 percent of GDP to the health sector to combat the health and economic fallout from COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. In absolute terms, 14 OECD countries raised real health spending by 5 percent, on average.

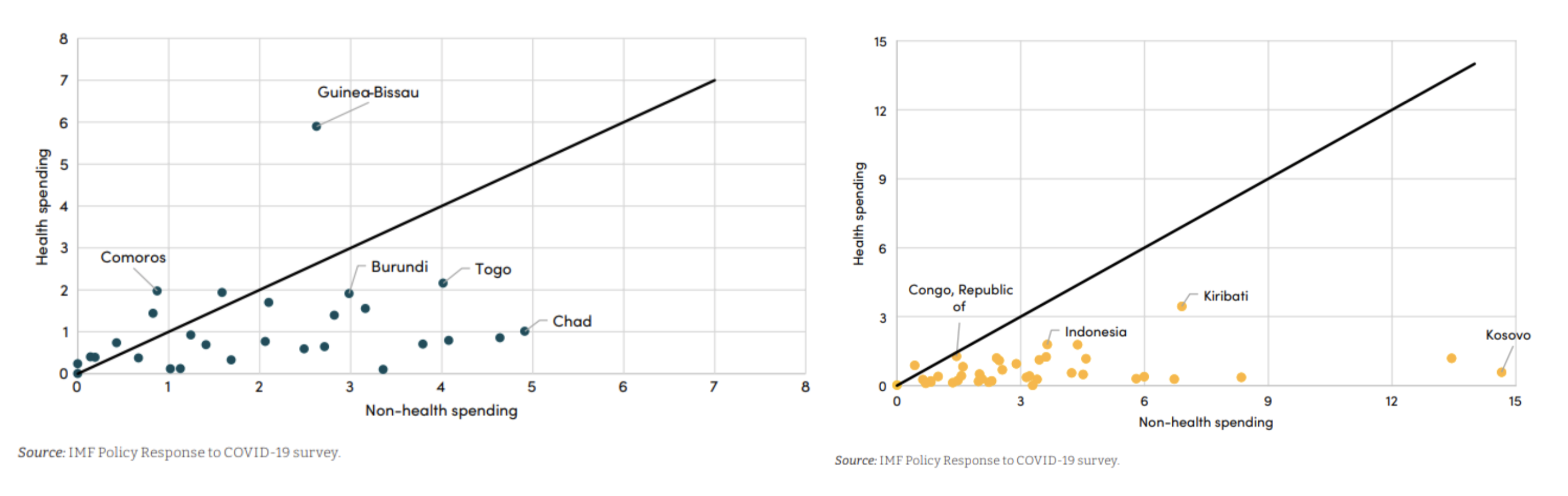

But even while countries were spending more on health, they also ratcheted up expenditure in nearly all other sectors (see Figure 1). In fact, the priority given to health spending within the overall government budget has declined in many countries. The WHO estimates that the share of health spending in total general government expenditure decreased in 2020; general government expenditure outpaced increases in public spending on health for 15 of 22 (mostly high-income) countries studied.

Figure 1. Increase in health and non-health spending in 2020, as a percent of GDP for low-income countries (left) and lower-middle-income countries (right)

Source: Assessment of Expenditure Choices by Low- and Low-Middle-Income Countries During the Pandemic and their Impact on SDGs. Reproduced from Gupta and Sala 2022.

Yet, few details are available on the uses of these spending increases. There is also little information on how “sticky” their uses have become; for instance, was spending mostly on a one-off basis to implement emergency immunization programs versus on recurrent costs like salaries? Comparable expenditure information on uses of external aid for COVID-19 is also hard to come by. For 15 reporting countries, the WHO estimates that about 58 percent of the increase in spending was externally financed in low-income countries and 28 percent in lower-middle-income countries in 2020.

2. Countries are unlikely to sustain pandemic-era health spending increases—and many are likely to undertake fiscal consolidation in 2023-4

Despite the unprecedented increase in health spending seen during the COVID crisis, low-income and lower-middle-income countries are unlikely to sustain higher levels of spending in the coming years. This is due to several interlinked factors: shrinking government revenues due to protracted economic impacts of the pandemic as well as projected declines in economic output related to the ramifications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rising inflation, and a looming recession.

The IMF is counseling fiscal responsibility and consolidation as a main policy instrument to control high and persistent inflation, including in low-income countries. As of December 16, 2022, there were 3 IMF stand-by agreements (including with Senegal) and 16 extended fund facility programs denoting a protracted balance of payments financing need and structural reforms, including measures to reduce spending.

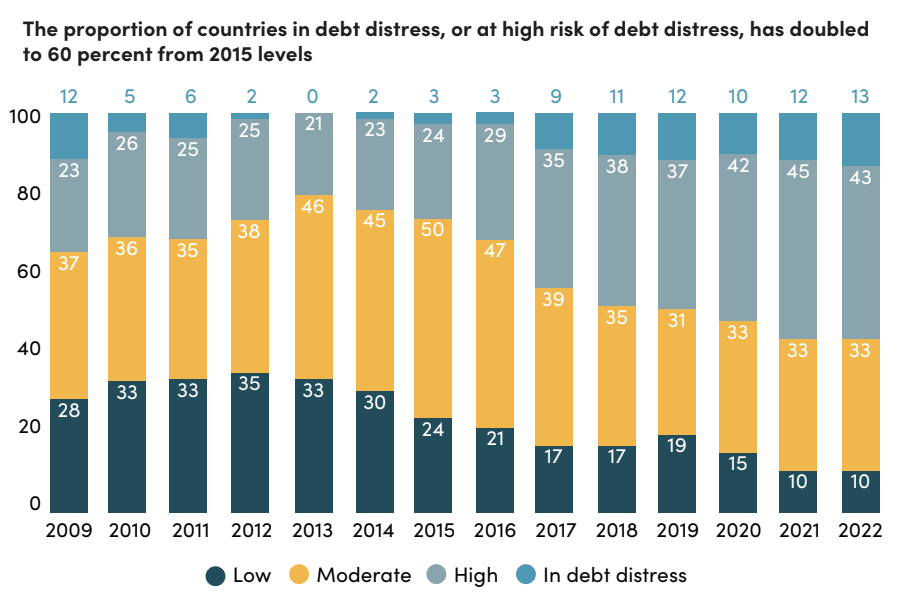

As global debt levels soar and interest rates rise due to inflationary pressures, debt service burdens, most notably of lower-income countries, are at unprecedented levels. IDA-eligible countries could see their debt-service payments on public and publicly guaranteed debt rise by as much as 35 percent in 2022, one of the highest annual increases in the last 20 years. The number of countries—most notably those in Africa and Pacific Island nations—in debt distress is growing (see Figure 2). 60 percent of African countries (22 countries) are already in, or at risk of, debt distress. Many of these countries are simultaneously facing intensifying climate pressures and very high levels of health risk factors. The case of Ghana is illustrative of a deepening crisis. By the end of 2022, debt servicing was consuming as much as 70-100 percent of national revenues, forcing the government to suspend debt payments and effectively default on its external debt.

Figure 2. Rising debt risks in low-income countries (percent of DSSI countries with LIC DSAs)

Note: Data as of March 31, 2022. DSSI = Debt service suspension initiative; LIC = low-income countries; DSAs = Debt sustainability analyses.

Source: Crisis Upon Crisis: IMF Annual Report. Reproduced from International Monetary Fund 2022.

With lower government revenues and interest payments driven by the high cost of borrowing, lower-income country health systems will face significant fiscal pressures. And low-income countries may be especially vulnerable to reductions in government health spending as government debt grows. The World Bank has identified 41 low-income and lower-middle-income countries where government spending on health between now and 2027 is likely to remain lower than pre-COVID levels. Some countries are also experiencing a confluence of overlapping pressures, with the potential for more severe implications on health service delivery, access, and equity. For example, per our tally, nearly one-third (13) of the 41 “health spending contraction” countries identified by the World Bank are already in, or at high risk of, debt distress.[3]

3. Disparities in health spending between countries are widening, further increasing inequalities

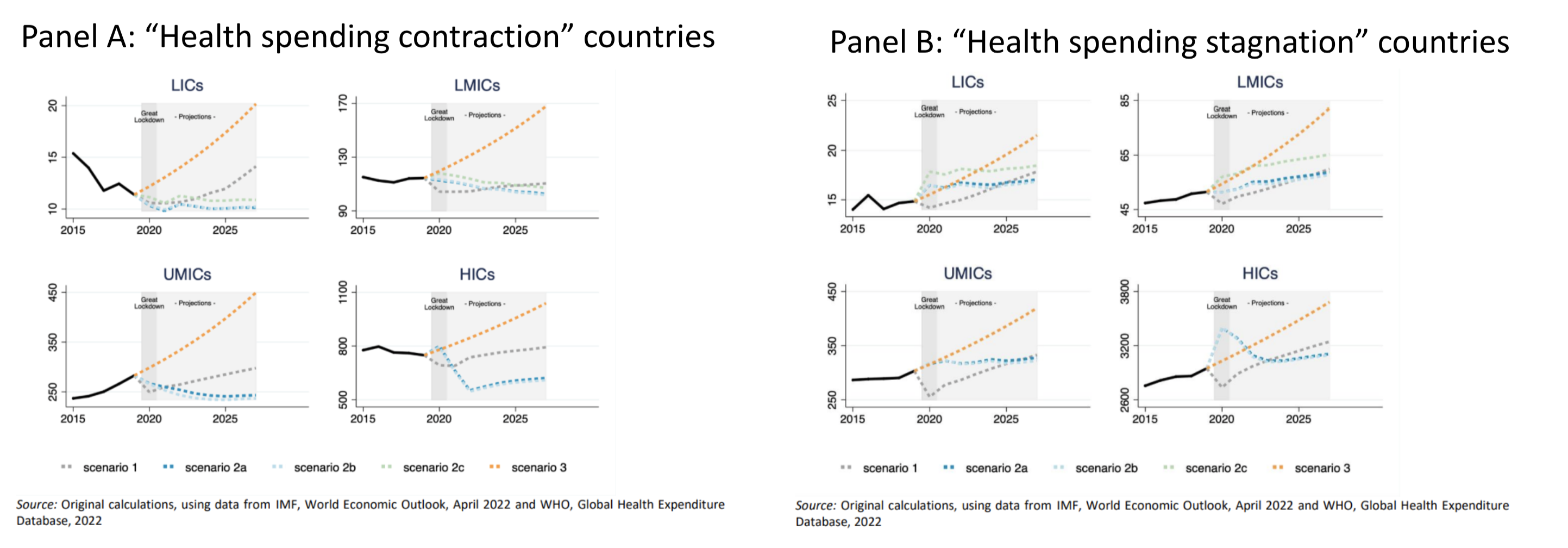

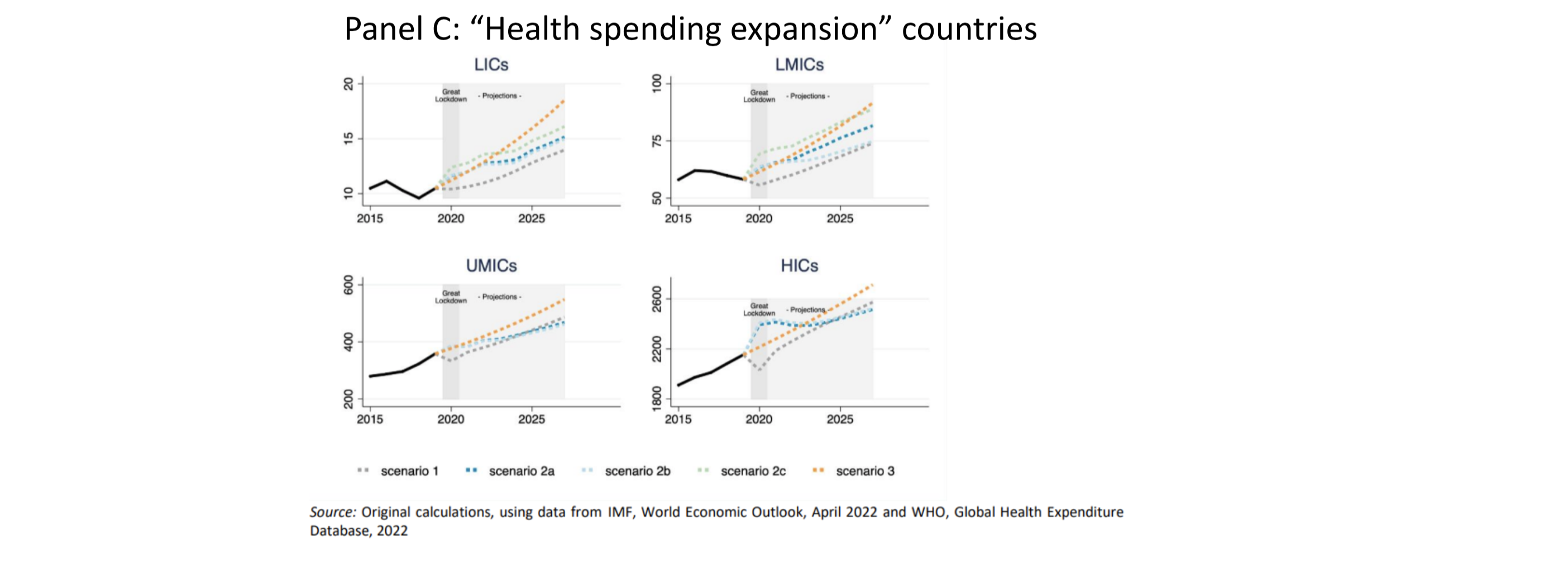

COVID-19 and its knock-on effects have exacerbated the massive differentials in health spending that already existed across countries long before the pandemic, further increasing inequalities. Recent projections from the World Bank suggest that in 41 “spending contraction” countries, government health spending from now until 2027 will be lower than pre-COVID levels; health spending in 69 “stagnation” countries will be almost on par with pre-COVID levels (see Figure 3).[4] These widening rifts will also impact countries’ abilities to prepare for and respond to future health threats, further increasing disparities when the next health emergency strikes.

The various projections of future trajectories of health spending are rife with assumptions and uncertainties. Still, they point to a consensus: lower-income country health budgets will experience a significant fiscal crunch at precisely a time when more—and better—spending is needed.

Figure 3. Per capita government health expenditure, by income group (constant 2019 US$)

Source. From Double Shock to Double Recovery – Implications and Options for Health Financing in the Time of COVID-19. Reproduced from Kurowski et al. 2022.

4. Few lower-income countries have health-specific counter-cyclical fiscal protections in place

Many low-income and lower-middle-income country economies do not have automatic ways to stabilize overall public spending in response to external shocks. Even fewer countries have budget or fiscal protocols to identify and protect essential spending on health or health sector spending directed towards the most vulnerable populations , or to adjust health benefits for rising inflation.

Instead, many LMICs depend on discretionary measures (whether health or social safety nets) to support this type of spending. As governments head into a period of fiscal consolidation, there will be an urgent need to revisit discretionary measures and build more durable ways to identify and protect essential spending, and to protect vulnerable people and communities, ideally in ways that optimize external aid for health channeled through global health and development institutions.

Policy options

The risky macro-fiscal outlook requires effective policy options, tailored to specific country contexts, to protect essential health coverage and spending in the face of intensifying budget pressures. In support of this agenda, global health and development partners must also revisit business-as-usual approaches. Understanding the broader development financing landscape—and its likely evolution—will be vital to assure fit-for-purpose approaches for 2023 and beyond.

Below we lay out policy options on the “menu” for governments and their global health and development partners to protect spending on high-impact essential health services and products, and the most vulnerable communities. While some policies focus on health sector spending, others seek to expand total government expenditure more broadly, with the precise impact on generating additional fiscal space dependent on the underlying context. The policy ideas presented below are not meant to be exhaustive; they all deserve further discussion, elaboration, and research. And ultimately, policymakers’ decisions about which options to use—and in what combination, as many of these options could be pursued concurrently—will depend on each country’s economic context, existing policy measures, and political will.

1. Prepare for fiscal consolidation and assess potential impacts of health spending reductions

In countries planning adjustment, government policymakers must identify financing modalities to protect essential services and the most vulnerable communities; help maximize impact and efficiency of spend at the country level; and reset expectations and reassess approaches around driving sustainability in health spending amidst the reality of multiple crises.

A first step should entail defining essential health benefits and products and their associated expenditures, identifying affected populations, and assessing potential human and economic impacts of spending reductions. Countries at high-risk for adjustment including in the health sector should develop specific proposals to protect coverage and spend and avoid across-the-board cuts that can negatively affect service delivery and health outcomes.

Several countries have participated in efforts to identify and model the costs of essential health services packages in countries at different levels of income[5] and guidance is available;[6] key coverage and related spending protection can build on these earlier tools and activities.

2. Assure that IMF programs and multilateral development bank (MDB) operations protect essential health and related spending

IMF programs, which are already in place, or under preparation, in many lower-income countries, represent one opportunity to assess and protect essential health spending during a period of fiscal consolidation. In partnership with governments, the IMF will assess spending for incorporation into revised macroeconomic frameworks looking at a range of issues that may relate to health spending.

Ministries of Health and Planning should stand prepared to proactively provide input into these assessments, with the support of external development partners, and to assure that any adjustment conditionality affecting the health sector is benign with respect to the financing and provision of essential services and the protection of the most vulnerable communities. There are also new IMF instruments (e.g., Resilience and Sustainability Trust) that can be mobilized for investment in pandemic preparedness.

MDBs will also be a critically important source of external finance for LMICs over the coming years, including via large budget support or adjustment operations to fill fiscal gaps. Budget support conditionality should include the maintenance of coverage of essential health interventions like child immunization, prenatal care, and management of infectious and non-communicable diseases, as well as protection of spending on these essential health services and associated health products. In addition, budget support operations can help drive reforms for efficiency gains, including improved public financial management, as well as actions to assure counter-cyclical fiscal arrangements within the health system to protect coverage and benefits, particularly for the most poor and vulnerable.

Spending in other social sectors, including social protection and education and even infrastructure, also matters for health outcomes, and vice versa. Protection of spending, and associated reforms, in these sectors should be considered alongside essential health spending and provision.

Finally, as the experiences of previous economic crises suggest, macroeconomic stability and control of inflation matters enormously in lower-income countries for health service utilization and overall health status at the household level. Rather than oppose needed macro-fiscal actions to stabilize economies, policymakers in the health sector, and global health advocates, should seek to assure that health is adequately prioritized as part of response measures.

3. Optimize the use of all available sources of global health concessional and grant resources

Global health funders should make another run at a consolidated offer to government partners and NGOs providing financing for the recurrent costs of care in the health sector. A more articulated effort between the large bilateral HIV programs like PEPFAR, the multilateral instruments like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the trust funds like the Global Financing Facility, and the broad health sector support and reform operations provided by the World Bank or regional development banks could be put together to better support governments undergoing adjustment and would also help with efficiencies. There have been many previous attempts to coordinate concessional and grant resources in the global health space that have fallen prey to competing institutional mandates and differing timelines, but there is again an emerging interest and opportunity to revisit pooling and combined operations, while maintaining a focus on the results that each fund or organization is aiming to achieve in partnership with country authorities.

One option is to “blend” grant financing from global health organizations, such as the Global Fund and the recently established Pandemic Fund, with operations and reforms defined and financed by governments in cooperation with MDBs to provide greater support to countries experiencing fiscal pressure in the health sector. Given the global credit crunch, the concessional terms of both IDA and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) lending—and regional development bank equivalents—is vital for the protection and pace of spending, with important implications for coverage of essential health services.

A related issue is to assure realism in co-financing expectations. Reducing and/or temporarily eliminating co-financing requirements may need to be on the table. For instance, in recognition of growing fiscal challenges, Gavi’s board recently expanded the timeframe for countries in the accelerated transition phase, enabling governments to more gradually scale up co-financing on the path to becoming fully self-financing. But global health partners may need to more fully rethink their transition policies, beyond simply extending the duration of the transition period, to account for new macroeconomic realities, as well as competing priorities within the health sector.

Finally, as countries restructure and renegotiate public debt, debt swaps linked to health offer another possible lever to create fiscal space.[7] Debt swaps are a financing mechanism whereby a creditor foregoes repayment on part, or all, of a loan, effectively converting debt payments owed by a country into available capital. In the case of debt swaps for health, countries agree to use these investments for the health sector. But this mechanism requires efficient coordination between creditors (bilateral, multilateral including the World Bank and regional development banks, or commercial) and indebted countries—and should be sufficiently tailored for specific contexts and uses.

4. Realize efficiency gains by cutting wasteful health spending

Limited health resources must be spent more effectively and efficiently—and in some instances savings can be generated without compromising the quality of service provision. Focusing on efficiency gains via better priority-setting is one policy option to help make available resources go further.[8] Specific health system functions, such as procurement, product selection, and product listing, can serve as important levers for generating savings.

Identifying high-cost items like medicines and other health products that constitute a sizeable share of public sector budgets can uncover potential areas for reform—and generate future savings. For instance, a 2015 review in Vietnam revealed that just 13 medicines were consuming more than a quarter of the total public budget for drugs, but most public expenditure on those medications was used for inappropriate or cost-ineffective purposes. In more recent work, overuse of medications has been found to be widespread within LMICs, across multiple drug classes, suggesting opportunities for rationalization for a class of public expenditure that is easily identifiable.

However, efficiency reforms generally require time and political will, and in low-income countries the baseline level of per capita expenditure is still extremely low, and the size of potential savings may be negligible.[9] Further, ministries of finance may not reinvest such gains back into the health sector, which reduces sectoral incentives to realize efficiencies. In other words, efficiency gains do not always translate into large increases in fiscal space for health.

5. Raise health taxes—and allocate additional resources to health budgets

Taxes are one tool governments use to raise revenues to invest in infrastructure, the provision of services for citizens, and key priorities like health care. Taxes on products that negatively impact health, such as tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages—or “health taxes”—would have a dual benefit: discouraging the consumption of unhealthy products, thus helping to reduce the prevalence of non-communicable diseases, and raising much-needed additional revenue for health.[10]

Estimates suggest that such health taxes could close at least half the revenue shortfall of LMICs in the near term. If revenues from taxes on health-harming products were channeled back into health systems, these could fill critical fiscal gaps in countries’ medium-term revenues. The same could be said for fossil fuel subsidies or “green taxes” on environment-harming emissions. However, improving tax administration presents a significant lift and reinvesting the revenues raises from these taxes into the health sector requires political commitment and is not guaranteed.

6. Reassess the mix between private and public spending

When seeking more funding to supplement scarce resources for health, spending in the private sector should also be considered. Private sector utilization and delivery plays a significant role in many LMIC contexts. Yet, adequate policies need to be in place to harness the private sector’s role and ensure due consideration to equitable access, accountability, and a focus on prevention and promotion alongside treatment. Private investment and public-private partnerships also deserve additional review and scrutiny to assure crowding-in of resources in the health sector.

7. Reallocate within existing budgets

Governments in lower-income countries prioritized health less than higher-income countries in their budgets even prior to COVID-19. For instance, in 2019, low-income country governments spent 7 percent of their budgets on health compared to 11.5 percent in upper-middle-income countries—with considerable variation across countries. Budget cuts to health, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic’s devastating impacts, could be extremely damaging to already struggling health systems. Any de-prioritization of health spend could stunt recovery from COVID-19 and lead to additional backsliding on key health indicators, including immunization coverage.

One—albeit obvious—way for countries to spend more on health is for governments to actively prioritize a larger share of their budget to the health sector. But considering limited fiscal space amidst competing budget priorities, compounded by high debt levels and the looming threat of recession, allocating more resources for health, while arguably important, would be challenging in the current climate.

Conclusion

The current macroeconomic and fiscal reality points to alarming trends of stagnating and declining levels of government spending on health in low-and lower-middle-income countries where unmet needs are the greatest. At the same time, the looming economic recession is squeezing donor resources.

There are no silver bullet solutions to these complex challenges. The global health community must engage in the development financing space with a full-throated and evidence-based ask and offer for the financing required to deliver on the promises of COVID-19 recovery, international goals for infectious disease and pandemic risk control, and universal health coverage. The current moment also calls for a reckoning with reality: unlocking significant additional resources for health will be challenging in the short-term and underscores the imperative to protect the vulnerable and essential services in a very difficult fiscal environment.

Pursuing ambitious reforms to the international financial architecture must be a top priority for 2023. Indeed, the future sustainability of health spending will, in part, depend on whether these efforts adequately deliver for health. Assuring health is sufficiently prioritized will be critical to supporting governments in their efforts to blunt catastrophic impacts on health systems and population health around the world.

[1] A recent OECD study on Latin American health systems shows that excess mortality was higher than other countries in the world especially in Peru and Mexico, and two to three times higher than the OECD average https://www.oecd.org/health/primary-health-care-for-resilient-health-systems-in-latin-america-743e6228-en.htm; https://pandem-ic.com/blog-covid-19-is-a-developing-country-pandemic/

[2] The excellent recent IFS study on the UK National Health Service makes these dynamics clear. https://ifs.org.uk/publications/nhs-funding-resources-and-treatment-volumes.

[3] Low-income countries: Liberia, Mozambique, South Sudan, Sudan; Lower-middle income countries: Comoros, Republic of Congo, Kiribati, Lesotho, Federated States of Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Vanuatu, Zambia. Based on data available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-toolkit/dsa

[4] The report also finds that 67 “expansion” countries, the majority of which are high- and upper-middle income countries, are likely to see increases in per-capita government spending on health, see https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/from-double-shock-to-double-recovery-health-financing-in-the-time-of-covid-19

[5] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30121-2/fulltext; https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)32906-9/fulltext

[6] https://www.jointlearningnetwork.org/resources/guide-for-health-benefits-package-revision/; http://dcp-3.org/translation/pakistan ; https://www.cgdev.org/publication/whats-in-whats-out-designing-benefits-universal-health-coverage

[7] Climate debt swaps are increasingly proposed, but some experts argue they may be less efficient than financing via grants. See, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/covid-19-and-budgetary-space-health-developing-economies

[8] https://www.cgdev.org/publication/priority-setting-health-building-institutions-smarter-public-spending; https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/whats-in-whats-out-designing-benefits-final.pdf; https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2022/English/wpiea2022048-print-pdf.ashx

[9] Per capita health spending (in real terms) in low income countries is $39, on average, per year, $125 per year in lower-middle income countries, and $515 in upper-middle income countries, compared with $3708 in high income countries. See: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/365133/9789240064911-eng.pdf#page=16

[10] https://www.cgdev.org/blog/why-we-need-hike-taxes-alcohol-tobacco-and-sugar; https://www.statnews.com/2022/11/30/excise-taxes-on-tobacco-alcohol-and-sugary-beverages-benefit-health-and-public-budgets/

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock