Recommended

Summary

Around the world, cash transfer programs are being rolled out by governments to mitigate economic hardship brought on by the ongoing pandemic. In Pakistan, the Ehsaas Emergency Cash Program was introduced in April and rolled out to four groups of beneficiaries, largely relying on mobile phone registrations and requiring a national ID to register. Due to large gender gaps in mobile phone ownership and national ID possession, women are at risk of being disproportionately excluded from the program. Using data from the 2018 Financial Inclusion Insights survey in Pakistan, we use the gender gap in mobile phone and ID possession to estimate the potential gender breakdown of cash recipients. Despite the program’s design guaranteeing women will make up at least 25 percent of recipients, we estimate that women will only make up 43 percent of recipients overall. This means that up to 78 percent of women in poverty will be excluded as direct recipients of Ehsaas Emergency Cash payments. If women do indeed have less access to the program, then overall economic gender equality may regress as a result of the pandemic and associated response efforts. To address this, the Pakistani government should ensure more women are able to access the Ehsaas Emergency Cash Program, potentially by reserving more slots for women or prioritizing women’s registrations.

Introduction

Governments are taking action to reduce both the health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 virus and the resulting global recession, prioritizing the leverage and expansion of existing social protection systems to mitigate economic hardship for poor populations. If well-designed and implemented, expanded social protection schemes can avoid exacerbating inequalities, including gender gaps in financial inclusion and economic security, and even work to narrow them. In the coming months and years, researchers and policymakers will learn more about the precise effects of social protection strategies on gender gaps in poverty rates and other economic outcomes.

For now, we can examine cash transfer and other social safety nets that are being rolled out to mitigate the harm of the COVID-19 economic slow-down, unpacking the details of their design and implementation. Do schemes target the head of household, or women only? Are payments delivered through mobile phones or other online platforms, or in urban centers rather than rural areas? Must recipients have a legal ID or access to an online portal to apply for support? The answers to these questions, combined with a clear understanding of pre-existing, intersectional gender gaps within a particular country context, can help us to predict where women and girls— and particularly those living in poverty, or in rural areas, or those lacking access to a phone or the internet—are at risk of being left behind. Overlaying data reflecting gender gaps onto information on the rollout of social protection schemes can also help us to correct for potential inequities and design better systems going forward.

In this policy note, we highlight Pakistan’s Ehsaas Emergency Cash program as a case study, as well as several other examples of cash transfer programs mobilized by governments in light of COVID-19, to reflect how this sort of preliminary analysis can be done.

Pakistan’s Ehsaas Emergency Cash Program: Context and History

Just as COVID-19 began to spread, Pakistan was already in the process of rolling out a new cash transfer scheme targeting women.

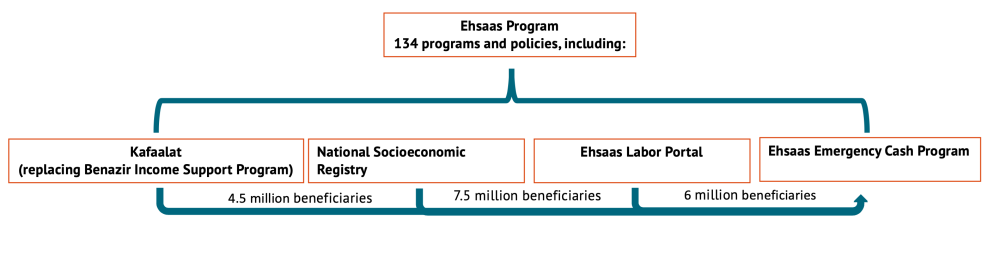

Pakistan’s Poverty and Alleviation and Social Safety Division is home to Ehsaas, an umbrella initiative of 134 policies and programs aimed at reducing poverty through social protection. Launched in 2008, the signature cash transfer program under the Ehsaas umbrella was previously the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP), which targeted women from the poorest households in the country. BISP identified recipients through a door-to-door paper survey and provided quarterly payments of PKR 5,000 (about USD $30).

In February 2020, recognizing the need for an updated cash transfer program, the government implemented the Kafaalat program to replace BISP. The Kafaalat program uses an updated door-to-door digital survey to identify recipients, and the payments are dispersed monthly (PRK 2,000/month, or about USD $12) rather than quarterly as under BISP. And though the BISP program did not automatically set up bank accounts for intended payment recipients, the Kafaalat program opens bank accounts for women in a conscious effort to increase their access to financial services. Targeting women more purposefully for cash transfers can contribute to economic empowerment by increasing decision-making power and control over resources in the household. The Kafaalat program is also linked with other initiatives under the Ehsaas umbrella, including programs to increase women’s mobile phone access and “graduation” programs aimed at transitioning people out of poverty.

When it was first announced, the Kafaalat program was designed to benefit 7 million women in Pakistan. As of March 24, 2020, it had enrolled 4.5 million recipients in the program, but because the program relies on in-person surveys to identify recipients, further enrollment has stalled due to the emergence of COVID-19.

Emergency social protection is being rolled out in Pakistan.

In response to COVID-19, the Pakistani government has implemented the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program, which is also housed under the umbrella Ehsaas program of the Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety Division. Families receive a lump sum of PKR 12,000 (approximately $75 USD), intended to contribute to basic food costs for four months. The cash transfer is delivered via biometrically-enabled cashpoints across the country. In April 2020, the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program was designed to reach 12 million families (an estimated 80 million individuals) with a budget of $900 million USD. The program was then expanded on May 18, 2020 to include an additional 6 million recipients. With an estimated 100-120 million individuals in recipient households, the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program is meant to benefit approximately 47-56 percent of the total population of Pakistan.

To implement the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program quickly, the government relied on several existing mechanisms also housed under the umbrella Ehsaas program (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Relationship of existing Ehsaas programming to Emergency Cash Transfer program

As of June 12, 2020, over 10.11 million recipients had received emergency cash assistance. The program has been rolled out to four categories of recipients, reflected below.

Table 1: Ehsaas Emergency Cash program rollout in Pakistan as of June 12, 2020

| Recipients | Targeting | Identification mechanism | Recipients served (millions) | Target number of recipients (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category I | Women only | Kafaalat program | 4.526 | 4.5 |

| Category II | Men and women | SMS and verified through National Socio-Economic Registry 2010 and 2020 | 3.296 | 4.0 |

| Category III | Men and women | SMS and verified through district governments | 2.295 | 3.5 |

| Category IV | Men and women | Web-based Ehsaas Labour Portal | Unknown | 6.0 |

| Total | 10.11 | 18.0 |

Category I recipients include all 4.5 million existing Kafaalat recipients. The Pakistani government acted strategically in leveraging the Kafaalat program for the rollout of emergency cash assistance as the pandemic evolved, given that the program had already identified 4.5 million of the poorest women in the country, and because the program had the additional goal of increasing women’s access to and use of formal financial institutions. These women continue to receive the regular Kafaalat payments, with an additional PKR 1000 (about USD $6) per month under the emergency cash scheme, for a total of PKR 12,000 (about USD $75) for four months, a 50 percent increase. This amount has been delivered as a lump sum, not monthly as originally planned.

Categories II and III of the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program target an additional 7.5 million individuals and utilize the National Socio-Economic Registry (NSER) system, also housed under the Ehsaas umbrella. These categories are open to both men and women, and require potential recipients to send an SMS message with their national identification numbers to the enrollment system, at which point their IDs are checked with the National Socio-Economic Registry to determine whether they fall below a certain socioeconomic cutoff. This cutoff is determined using a 100-point means test, where those scoring below 32 points qualify for Category II. Individuals are also checked against several other databases and may be excluded for a variety of other factors, including public employment, international travel, vehicle registrations and utility bills above a certain level. For those who do not qualify or are not in the registry, they are moved to Category III, which refers the cases to commissioners at district level to verify eligibility.

On May 18, 2020, due to high demand for the program, a fourth category was added. This category will target an additional 6 million recipients who have lost their incomes due to the pandemic, but it is unclear what the specific criteria for eligibility will be. Potential recipients will apply through the online Ehsaas Labor Portal. To register under this category, recipients must still provide a mobile phone number and a national ID number, and answer questions regarding their lost income.

Table 2: Amount dispersed and withdrawn by beneficiary category (as of June 12, 2020)

| Recipients | Amount disbursed(millions Pakistan Rs.) | Amount withdrawn (millions Pakistan Rs.(% of amount disbursed) |

|---|---|---|

| Category I | 60,419 | 55,890 (92%) |

| 47,966 | 39,562 (82%) | |

| Category III | 41,701 | 27,542 (66%) |

| Category IV | Unknown | Unknown |

The current approach has been rolled out quickly to meet immediate needs – but has limitations.

The Pakistani government has moved quickly to respond to poverty and food security concerns in light of COVID-19, and has done so harnessing innovative technologies. That said, the current approach has limitations in meeting citizens’ immediate needs. For example, the program assumes a household size of 6.7 people, meaning a PKR 12,000 (USD $75) lump sum works out to roughly $11.25 USD per person, or $0.09 USD per day. Using World Development Indicators, per person daily consumption for the poorest 40 percent of the population in Pakistan is estimated at $2.60 USD, so the amount of the transfer is only a small portion of daily consumption.

The program’s approach also risks unintended consequences, particularly those related to gender inequality in the country. With the rollout of such a large-scale social protection program, the Pakistani government has an opportunity to not only provide immediate relief to those struggling economically due to COVID-19, but also to “build back better” by narrowing existing gender gaps in financial inclusion. But because the current rollout strategy relies heavily on individuals’ ability to send an SMS or access an online portal, as well as have a national ID, to apply for support, women are at a disadvantage in their ability to access payments. Considered against women’s financial and digital exclusion in the Pakistani context, the rollout strategy risks exacerbating gender gaps in financial inclusion as well as economic security.

Pakistan has wide gender gaps in financial and digital inclusion.

According to most recent estimates, nearly 36 million women (51.26 percent) live in poverty (under $2.50 USD/day PPP) in Pakistan. Furthermore, 7.53 percent of all women live in extreme poverty, on less than $1.25 USD/day. These statistics, however, may underestimate women’s poverty levels. Because estimates rely on household level data, which does not account for the unequal distribution of wealth within the household that often disadvantages women, women’s poverty rates in Pakistan may be higher.

The 2017 Financial Inclusion Insights survey from Pakistan elucidates key gender gaps in financial inclusion. Across indicators, women have significantly less access to financial services. The percentage of women who own a bank account in their own name (6.2 percent) is less than half the percentage of men who have their own bank account (15.2 percent). The picture remains bleak when including jointly owned bank accounts; only 0.73 percent of women and 1.79 percent of men have their name on a joint bank account. The numbers are similar when looking solely at women in poverty, with only 5.41 percent of women in poverty owning bank accounts solely, and 0.23 percent of women owning them jointly. Taken together, it is clear that formal financial services are not widespread in Pakistan overall, but they remain especially unattainable for women.

Figure 2: Percent of women and men who have bank accounts

Beyond ownership of bank accounts, women also have more limited access to national identification cards, limiting their ability to access other financial services and government social protection schemes, as well as exercise their broader social and political rights. An estimated 89.4 percent of men in Pakistan have a national ID card, compared to only 82.9 percent of women. For men and women in poverty, these numbers actually increase to 90.24 percent and 85.76 percent respectively. This increased prevalence of national IDs among the poor may be due to prior registration for government social programs.

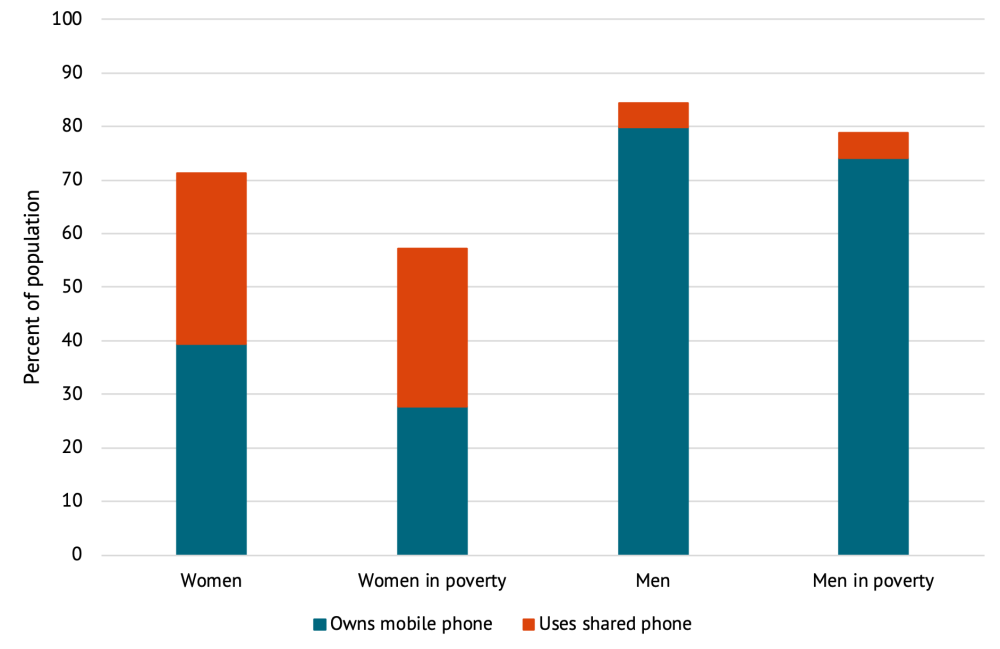

Women in Pakistan are also are less likely to own mobile phones. Only 39.35 percent of all women and 27.76 percent of women in poverty own mobile phones, whereas 79.77 percent of all men and 74.13 percent of men living in poverty own phones. Financial constraints may contribute to gender gaps; when a household is not able to afford multiple mobile phones, men in the household get priority. And even in non-poor households, gender norms constrain women’s access to mobile phone ownership. Women are much more likely than men to use a phone owned by someone else, usually in the same household. Of all women, 31.92 percent use a shared phone compared to only 4.63 percent of all men. For those in poverty, 29.38 percent of women use a shared phone compared to 4.81 percent of men.

Figure 3: Percent of women and men with access to a phone

Even if women have access to a phone, they are less likely to be able to perform the functions required to register for Categories II and III of the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program. When asked to judge their own ability to send and receive text messages on a scale of one to five, with five signifying complete ability to do so, women in poverty gave themselves an average rating of 1.89 (roughly “a little ability”), while men in poverty gave themselves an average 2.84 (roughly “some ability”).

Gaps may be exacerbated by the planned rollout of emergency cash assistance.

Because women in Pakistan are less likely to have both a mobile phone and a national ID than men, they will have differential access to the Ehsaas scheme. When these two disadvantages are combined, only 25 percent of women in poverty have both a mobile phone and a national ID, compared to 68 percent of men in poverty.

Gender gaps in financial inclusion, as well as broader economic security, could become larger with its rollout. Starting the Ehsaas Emergency Cash rollout with 4.5 million women already receiving payments through Kafaalat was an excellent step in ensuring women would receive needed financial support. Apart from this earmarked portion, however, women will face an uphill battle for access to the other 13.5 million slots, as no other slots are guaranteed to women.

As it currently stands, the rollout ensures at least 25 percent of Ehsaas Emergency Cash recipients are women, covering 12.5 percent of women in poverty. But gender gaps in access to phones, bank accounts, and ID suggest that women will not have an equal opportunity to access the other 75 percent.

In a scenario where the proportion of women who successfully enroll via Categories II, III, and IV is equal to the proportion of women among those in poverty who have both a national ID and their own mobile phone (25.44 percent women), then only 3.4 million additional women will enroll, resulting in a total of 7.9 million women among Ehsaas Emergency Cash recipients. Under the same scenario, about 75 percent of the slots under Categories II, III, and IV would go to men, totaling 10 million men. This scenario still excludes 78 percent of women in poverty as direct recipients of Ehsaas Emergency Cash payments.

Figure 4: Estimated number of cash transfer recipients by category and gender

Of course, even if payments are overwhelmingly delivered to men, it is possible to respond to this concern by asserting that payments delivered to men will still benefit women and girls in their households. This is almost certainly true to a degree, but equitable distribution of resources cannot be assumed across the board. Both the Kafaalat program and the BISP program preceding it targeted payments at women for a reason: evidence across contexts suggests that when women control household resources, including cash transfers, they are more likely to be allocated in a way that benefits the next generation, improving children’s health and education outcomes, and the outcomes of women themselves. And while some recent evidence has reflected that fathers may be equally likely to allocate resources in ways that improve children’s outcomes in some cases, directing cash transfers to men is not yet proven to ensure adult women’s outcomes improve to an equal extent.

Targeting more women for emergency cash assistance can serve the dual purpose of providing immediate relief and narrowing gender gaps.

In light of these findings, the Pakistani government has an opportunity to ensure women have equal access to the emergency cash program, or even preferential access in order to mitigate the existing gaps in financial inclusion.

Some features of the existing Ehaas scheme already support this objective. Because cash is delivered via biometrically-enabled cashpoints, women’s control over the money may increase. Some evidence suggests that Pakistani women with low levels of literacy and numeracy have a difficult time operating ATMs that require a debit card or a PIN number, and therefore may have male family members or hired middlemen go to withdraw the money instead of going themselves. Some women may also face restrictive household or community attitudes, limiting their free mobility. But with a fingerprint verification system, Ehsaas Emergency Cash ensures that women must withdraw cash transfers themselves. Of course this says nothing about what happens to the funds once women return home, but ensuring women receive the money is a positive start.

Key Takeaways from Pakistan

There is an obvious trade-off between needing to roll out the Ehsaas Emergency Cash program quickly to mitigate the effects that households face in light of economic crisis, and designing and implementing the program conscientiously so that gender gaps in financial inclusion are narrowed, or at the very least, not exacerbated. Under normal circumstances large scale social protection programs provide an opportunity to systematically open bank accounts for poor populations and make formal financial services available to them, but time is of the essence in light of COVID-19.

That said, the Pakistani government can still take steps to prioritize women’s enrollment in the emergency cash scheme via Categories II, III, and IV. The Pakistani government could announce, for example, that priority in processing applications should be to those submitted by women (using their own national ID numbers) on behalf of their families. Women would then need to go themselves to the pay points to retrieve payments. Longer-term, the Ehsaas program —and others like it across countries —will need to prioritize broader inclusion efforts to ensure that women without a national ID or access to digital platforms, likely those in greatest need of cash relief, are not inadvertently excluded from social protection schemes.

Zooming Out: A Quick Snapshot from Other Countries

Other governments have employed different models to provide immediate cash relief and attempt to reach the most vulnerable women. The Indian government, for example, has also leveraged an existing financial inclusion program, Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), to roll out an emergency cash transfer scheme, but has delivered the emergency cash only to accounts registered to women. Having 100 percent of the funds delivered directly to women may address some of the intrahousehold inequalities referenced above, though the program is still inaccessible to over half of poor women. Using the 2018 Financial Inclusion Insights survey for India, Pande et al. estimate that 53 percent of poor women in India will be excluded from emergency cash relief.

If targeting women is difficult because the government is having trouble identifying potential women recipients, Mexico provides an example of a work around. To rapidly identify vulnerable households in Tlaxcala, Mexico, in April 2020 the state government created a new program designed especially for women-headed households, Supérate Mujeres, as an extension of the Supérate poverty reduction program. To quickly identify potential recipients, the government simply looked to the roster of the recently dismantled Prospera program and rolled those beneficiaries into the new cash transfer scheme. Where enrollment in Pakistan’s Kafaalat program has stalled and it is impossible to identify new recipients using that platform, one option could be for the government to turn to the recently closed BISP roll and enroll women from that list.

Governments can also consider varying cash amounts by gender of recipients to correspond to predicted need, including through recognizing that women may need additional support to account for their unpaid care work burdens, already disproportionate and potentially increased in light of COVID-19. This was the case in Togo, which introduced the Novissi cash transfer in April targeted at informal workers who lost their livelihoods due to COVID-19. The program was implemented for three months until June 15, 2020, at which point the country began the process of lifting lockdown measures and the program was ended.

Like the Pakistani model, the Togolese program required an ID and a phone, and cash was delivered directly to mobile money accounts. The amount of the cash transfer was different according to gender, with men receiving the equivalent of $18.12 USD per month and women receiving $21.14 USD. Women made up about 65 percent of cash recipients, suggesting that the Novissi program should be examined further to understand how women can be at least equally, if not predominately, targeted by cash transfer schemes.

Conclusion

Researchers and policymakers still have a lot to learn about the most effective means of ensuring women and girls equally benefit from social protection schemes, and that such programs work to promote broader equality. We have more to understand, for example, regarding the effects (and cost effectiveness) of targeting vulnerable populations versus unrolling universal cash transfer schemes, or varying amounts of cash delivered based on recipients’ varying levels of vulnerability.

But as the evidence base expands, there are still critical lessons to keep top of mind now. In the first instance, policymakers must remember that cash transfers are not rolled out in gender-equal contexts. Pre-existing gender gaps in access to ID, mobile phone ownership, financial literacy skills, and more mean that if cash transfer programs ignore these realities, they are likely to exacerbate gaps. Where resources allow, the evidence suggests that cash transfers must be complemented by the provision of ID, bank accounts, and mobile phones, as well as investments that increase financial, digital, and even basic literacy and numeracy, to ensure that progress in economic gender equality does not stall or regress.

Thanks to Alan Gelb, Amanda Glassman, and Masood Ahmed for comments. All errors are our own.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.