Recommended

This note summarizes two years of research under the Center for Global Development project “Governing Data for Development,” led by Michael Pisa and Ugonma Nwankwo along with project co-chairs Pam Dixon and Benno Ndulu.[1] The project was funded by the Hewlett Foundation and guided by a working group of 15 experts.[2] For more information, please visit the project website.

As data and digital tools assume an ever-larger role in all aspects of our lives, it is increasingly important to have clear and effective rules that govern how different actors can use personal data through its life cycle and across different data ecosystems. A key challenge for governments is establishing rules that protect citizens from harm while supporting useful innovation from both the public and private sectors.

Over the course of the Governing Data for Development project, we asked more than 100 experts from government, civil society, the private sector, development organizations, and the data governance and privacy communities for their views on the most significant challenges governments face in using and regulating the use of data to meet their development aims. Almost every expert we spoke with cited at least one of the three following obstacles:

- A lack of funding and political impetus needed to strengthen systems to manage data;

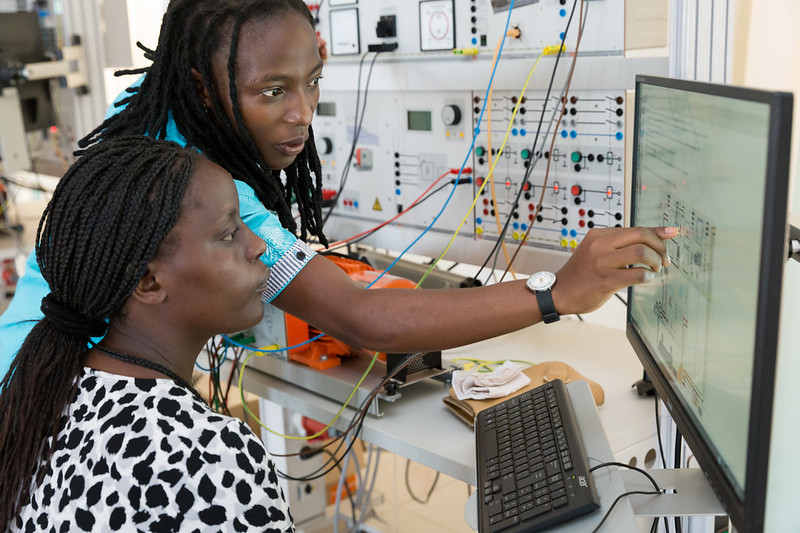

- A shortage of people with the technical expertise needed to create and work within those systems;

- Uncertainty about how to comply with (often new) national laws governing the use of data.

Until recently, the development community has paid substantially more attention to the first two challenges than the third.[3] This has changed over the last several years, however, as the sector has begun to grapple with how to promote responsible data use, in line with a broader shift in societal views about the risks of data misuse and mounting concerns about digital surveillance and the growing role of AI.[4] The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of using data responsibly by forcing a conversation on the limits that should be placed on governments seeking to use personal data to support public health efforts.

Although data protection policies are just one element of a broader nexus of laws, regulations, and norms that determine how countries govern the use of data, they play an outsized role. For many governments, establishing a data protection regime is a foundational step in developing a broader approach to modern digital governance. The choices that policymakers make when creating and implementing data protection laws set a trajectory for how a government and its citizens will engage with digital ecosystems and data. These choices, therefore, have direct and long-lasting consequences for economic development.

While the experts we spoke to for this project welcomed the growing number of countries that have enacted data protection regimes in recent years, they also raised concerns about the effectiveness of these regimes in practice, the challenges resource-constrained governments face in implementing them, and the potential negative consequences of poor implementation.

In this note, we review lessons learned through our research over the last two years and offer suggestions for policymakers seeking to regulate data use while keeping up with rapidly evolving digital practices and recommendations for how the international development community and high-income countries can promote a more inclusive and level playing field.

Why data protection matters for economic development

Effective data protection laws and regulations help build trust in digital tools and systems by establishing rights that protect citizens against the misuse of their personal data and obligations that require organizations to use data in a fair, transparent, and accountable manner. In theory, this greater trust should translate to greater acceptance of services that rely on data sharing and data use, leading to more investment in the resources and expertise needed to fuel a country’s digital transformation and support evidence-informed policymaking (World Bank, 2021; Bhaskar and Chaturvedi, 2017; World Economic Forum, 2019).

To meet these aims, however, data laws and regulations must be well-designed, tailored to local realities, and effectively and consistently enforced. Unfortunately, early evidence suggests that in many countries that have enacted data protection laws, enforcement is weak, regulatory authorities lack independence, and policies are not designed in line with existing resource constraints.

Data protection rules that are poorly designed or inadequately enforced can hinder economic development through different channels that can be roughly categorized as under-regulation, over-regulation, and regulating the wrong things in the wrong way.

-

Under-regulation: Even when data protection laws exist “on the books," they often fail to translate into "law on the ground" (Pisa, Dixon, Ndulu and Nwankwo, 2020). This weakens the level of protection provided and undermines the trust in data use and sharing that data protection laws are meant to instill. It also contributes to regulatory uncertainty, which can hinder useful data innovation by both the public and private sectors (Mungan, 2019).

-

Over-regulation: As in other sectors, over-regulation in the form of high compliance costs that bear little relation to improvements in desired policy outcomes have the potential to slow innovation by creating an unnecessary disincentive to investment. These costs are especially damaging to small- and medium-sized enterprises, which typically lack the well-resourced legal teams needed to navigate complex compliance requirements. (UK Digital Competition Expert Panel, 2019; Voss, 2021).

-

Regulating the wrong things in the wrong way: Several theorists have argued that current approaches to data protection place too much emphasis on protecting against individual harms and not enough on collective harms, putting it at odds with the growing reliance on machine learning algorithms that extract insights from collective data. (Tisné and Schaake, 2020; Moerel and Prins, 2016). Overemphasis on protecting against individual harms is mirrored by overreliance on informed consent as the primary basis for data processing, which often places an unreasonable burden on individuals and is meaningless in situations where they lack a basic understanding of how their data will be used (Medine, 2020; Selinger and Hartzog, 2020).

By undermining people’s trust in how their data is used and raising hurdles to responsible innovation, each of these conditions seems likely to lead to less investment in digital tools and data-driven services. But empirical evidence is lacking. Developing a better understanding of the causal pathways through which data regulations can affect a country’s digital and economic development is crucial to designing effective policies.

The global data protection landscape is marked by disparate resources and an uneven playing field

Modern approaches to data protection can be traced back to the establishment of the Fair Information Practices in the United States in the 1970s and the subsequent codification of and expansion on those principles by the OECD in the Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data published in 1980. The years that followed were characterized by a slow and steady diffusion of national data protection frameworks, mostly in wealthier countries, based and building on these principles (Gellman, 2021).

Over the last two decades, however, the number of countries that have adopted data protection legislation has significantly increased. Just since 2010, 64 countries — most of which are in Africa, Asia and Latin America and over 70 percent of which are categorized as LMICs— have enacted new data protection laws, bringing the total with such laws in place up to 146 (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Data protection and privacy legislation around the world

Note: Data from Greenleaf’s Global Tables of Data Privacy Laws and Bills (6th Ed January 2019); Greenleaf and Cottier’s 2020 Ends a Decade of 62 New Data Privacy Laws; and UNCTAD’s Data Protection and Privacy Legislation mapping. Additional research conducted by World Privacy Forum and Center for Global Development.

Several factors are driving the recent rapid adoption of national data protection frameworks, among them growing awareness of the risks of data misuse; the desire to create an enabling framework for responsible data use and sharing; the need to meet requirements of international development partners; and the catalytic effect of the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which was enacted in 2016 and came into effect in 2018. Of the more than 60 countries that have enacted new data protections laws over the last decade, almost all modelled their approach in full or in part on the GDPR and its predecessor, the 1995 EU Data Protection Directive (DPD).

The GDPR altered the global data protection landscape by providing a more rigorous model for protecting the privacy of individual data than had previously existed and established the EU as the global leader in regulating data. The regulations provided mechanisms that strengthened individual control over how data is used, increased the accountability of data controllers, and raised the stakes for non-compliance through greater fines and penalties. In contrast, the United States, home to the world’s largest tech firms, has taken a sectoral and relatively hands-off approach to regulating the use of personal data at the national level, with exceptions around certain categories of data, including health data and data pertaining to children.

The influence of the GDPR and DPD also reflects the extraterritorial scope of EU adequacy frameworks, which call on the European Commission to determine whether non-EU countries “offer guarantees ensuring an adequate level of protection essentially equivalent to that ensured within the Union, in particular where personal data are processed in one or several specific sectors” as a basis for transferring data (EU General Data Protection Regulation - Recital 104, 2016).

Because companies based in countries that receive a favorable adequacy determination face lower barriers to doing business with EU citizens, achieving adequacy confers a significant competitive advantage in the global digital economy. For example, a report issued before the UK achieved GDPR adequacy estimated that not receiving it would cost UK firms between £1 billion and £1.6 billion due to the additional compliance obligations (McCann, Patel and Ruiz, 2020). The risk is that failure to achieve adequacy will set countries that are already behind on their digital transformation even further back.

Although a growing number of countries have incorporated elements of the GDPR into law, early and anecdotal evidence suggests that most of them struggle to implement it effectively due to its breadth and complexity (Davis, 2021; Dixon 2019). Even EU member states, which had roughly 25 years of practice implementing a similar framework under the DPD, have struggled to implement the updated law (European Commission, 2020; Voss, 2021). The challenge is much greater for countries that face severe resource constraints, have a smaller pool of experts to draw from, and have less experience implementing a comprehensive data protection framework.

The scale of the challenge is illustrated by wide regional disparities in the level of human and financial resources available to data protection authorities (DPAs), which are the institutions responsible for interpreting and enforcing data protection laws in most countries that have comprehensive data protection frameworks (Table 1). Not only do DPAs in lower income countries face severe resource constraints, they also are more likely to lack functional independence from the executive branch or other ministries, which makes it difficult for them to resist political influence or to hold other government actors accountable (Davis, 2021).

Table 1. Regional differences in staffing and budget among data protection authorities

| Median Per-country DPA Budget | Median Per-country DPA Staff | |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| North America | $58 million | 647 |

| Asia/Oceania | $6.9 million | 77 |

| Europe | $2.2 million | 34 |

| Africa/Middle East | $500,000 | 14 |

| Central And South America | $400,000 | 13 |

| OECD | ||

| Member | $6 million | 50 |

| Non-member | $500,000 | 17 |

Source: Fazlioglu, 2018

Acknowledging the difficulties of implementing the GDPR framework is not an endorsement of watering down existing rules or taking an entirely different approach. In fact, the experts we spoke to were nearly unanimous in their support of the principles that underlie the GDPR and in their belief that countries should take a comprehensive and rights-based approach to personal data protection (as opposed to a sectoral approach or one that seeks to achieve an economic balance of interests) (Pisa and Nwankwo, 2021).

Many of the same experts expressed frustration, however, with how current arrangements for governing cross-border data flows have, in their view, unduly restricted domestic policy choices. This includes the GDPR adequacy process, which they regarded as excessively opaque and often driven by political and economic considerations, rather than the fitness of a country’s data protection regime. (Pisa and Nwankwo, 2021). For example, although the European Commission granted Japan adequacy in 2019 despite key differences between the GDPR and Japan’s model of cooperative data privacy, it has not granted adequacy to any country in Africa, despite several countries having data protection frameworks that are closely modelled on the GPDR.

Lack of coordination on data regulations at the global and regional levels further disadvantages low- and middle-income countries who, on their own, lack the economic leverage needed to influence both the practices of big tech companies that dominate global data flows and the terms on which cross-border data flows are governed in bilateral agreements with wealthier countries (for an example of the latter, see Rutenberg and Omino: Why the US-Kenya Free Trade Agreement Negotiations Set a Bad Precedent for Data Policy).

Future-proofing data regulation

Although lower income countries face unique challenges in getting data regulation “right” due to their greater resource constraints and more limited economic leverage, the problems they face are universal. Our research suggests the following lessons for policymakers trying to regulate data use while keeping up with fast evolving digital practices:

-

Think Local… While the GDPR’s global influence has resulted in similarities across national data protection frameworks, beliefs about data policy remain highly contextual, reflecting differences in local norms about data use, resharing, and privacy. One way for regulators to mitigate this tension is by working with different sectors to co-create guidance and codes of practice that can simultaneously help companies better understand their compliance duties and help regulators better tailor regulation to local conditions (for an example, see Data Protection Code of Practice for Digital Identity Schemes in Africa).

-

…But Don’t “Localize” Data Without Good Reason. It is increasingly common for data protection regimes to include localization measures that require firms that collect data about a country’s citizens to store or process that data within the same jurisdiction. While national security and law enforcement concerns may provide valid reasons to limit cross-border data sharing in certain limited instances, these measures can harm local companies by preventing them from using foreign cloud service providers that often deliver cheaper, higher quality, and more secure data storage options than domestic providers (UNCTAD, 2013; Levite and Kalwani, 2020).

-

Invest in improving knowledge and capacity. Low levels of digital literacy in the general population and among policymakers present a major hurdle to effectively implementing data governance and protection laws. Additionally, citizens must know their data rights and be equipped with the skills needed to question why their data is being collected and how it will be used. Experts noted that while DPAs have an important role to play in educating the public about their digital rights, they are often too resource-constrained to do so in practice.

-

Foster approaches that move beyond consent as the primary basis for protecting personal data. Relying on individual consent places an unreasonable and unworkable burden on individuals. Additionally, in complex data ecosystems, obtaining consent is not always possible. Policymakers should therefore consider ways to support testing and measuring the effectiveness of different models of personal data protection and enforcement, including, for example, legitimate purposes tests, data fiduciaries and trusts, and participatory data stewardship approaches (Medine and Murthy, 2020; Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021; Hardinges, Wells, Blandford, Tennison, & Scott, 2019; Wylie and McDonald, 2018; Moerel and Prins, 2016).

What can the international community do to support a more inclusive and level playing field?

Our research suggests several ways the international development community and high-income countries can promote a more level playing field for data protection policies and help LMICs advance on their path of digital transformation:

As a first step, jurisdictions should be transparent about how they reach adequacy decisions, including publicly stating why decisions are denied or delayed for certain countries. Beyond this, countries should agree to a set of standards to govern cross-border data flows that are strong enough to ensure high-quality data protection but flexible enough to allow governments to design frameworks that meet their own needs, priorities, and capacities. The Council of Europe’s Convention 108+, which is the only legally binding multilateral instrument on the protection of privacy and personal data, provides a model of such an outcomes-based yet flexible arrangement, but governments may be more likely to ratify a framework whose design they have provided input on.

-

Devote more resources to strengthening domestic data governance and protection regimes, in line with the countries’ needs and capacities. Development organizations should work with client countries to make sure their data governance and protection frameworks can support digital transformation. Improving how these frameworks are implemented and enforced should be a key focus of funding vehicles to support more and better data use such as the World Bank’s recently announced Global Data Facility (Hammer, Kaushik, Song and Rickets, 2021). Funding vehicles aimed at supporting data and statistics priorities like the World Bank’s recently announced Global Data Facility should make strengthening and measuring the effectiveness of data governance a key focus of their lending (Hammer et al., 2021).

-

Promote a common, transparent, and flexible approach to establishing the legality of cross-border data flows. The GDPR adequacy process is opaque and easily politicized. As more countries establish their own mechanisms for determining the legality of cross-border data flows, there is a danger that a proliferation of national data protection adequacy regimes could further fragment the global digital economy, unless they are anchored to a similar set of standards and adequacy assessments are conducted transparently.

As a first step, jurisdictions should be transparent about how they reach adequacy decisions, including publicly stating why decisions are denied or delayed for certain countries. Beyond this, countries should agree to a set of standards to govern cross-border data flows that are strong enough to ensure high-quality data protection but flexible enough to allow governments to design frameworks that meet their own needs, priorities, and capacities. The Council of Europe’s Convention 108+, which is the only legally binding multilateral instrument on the protection of privacy and personal data, provides a model of such an outcomes-based yet flexible arrangement, but governments may be more likely to ratify a framework whose design they have provided input on.

-

Foster global and regional initiatives to harmonize national data policies that give LMICs a seat at the table. To date, LMICs have had little input into global debates on data policy standards, leaving them in the role of “standards-takers.” Giving LMICs a meaningful voice in shaping the standards they are expected to meet makes effective implementation more likely. This will likely require the creation of new institutions as “existing institutional frameworks at the international level are not fit for purpose to address the specific characteristics and needs of global data governance” (UNCTAD Digital Economy Report 2021).

-

Identify and develop better data policy metrics. Currently, most cross-country measures related to data protection focus solely on legislation (Greenleaf, 2019; Chen, 2020; UNCTAD, 2020). New metrics are needed to better understand the relationship between data protection policies and economic outcomes, including on how well or poorly data protection measures are implemented, the effect of these measures on protection and investment outcomes, and the value created by key data ecosystems, cross-border data flows and data-driven innovation more broadly. The lack of such metrics is an obstacle to understanding which policies are working and which need reform.

References

Ada Lovelace Institute. (2021). Participatory Data Stewardship: A Framework for Involving People in the Use of Data. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/participatory-data-stewardship/

Chakravorti, B., & Chaturvedi, R. (2017). Digital Planet 2017: How Competitiveness and Trust in Digital Economies Vary Across the World. The Fletcher School, Tufts University, Medford, MA. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://sites.tufts.edu/digitalplanet/files/2020/03/Digital_Planet_2017_FINAL.pdf

Chen, R. (2020). Mapping data governance legal frameworks around the world: Findings from the Global Data Regulation Diagnostic. In Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank, Washington, DC. Retrieved 09 13, 2021, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35410

Davis, T. (2021). Data Protection in Africa: A Look at OGP Member Progress. Open Government Partnership, Washington, DC. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/OGP-Data-Protection-Report.pdf

Digital Competition Expert Panel. (2019). Unlocking Digital Competition. Retrieved 11 03,2021, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/785547/unlocking_digital_competition_furman_review_web.pdf

Dixon, P. (2019). Roundtable of African Data Protection Authorities. Retrieved 11 15, 2021, from https://www.id4africa.com/2019/files/RADPA2019_Report_Blog_En.pdf

European Commission. (2020). Data protection as a pillar of citizens’ empowerment and the EU’s approach to the digital transition - two years of application of the General Data Protection Regulation. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELE

Fazlioglu, M. (2018). How DPA Budget and Staffing Levels Mirror National Differences in GDP and Population. International Association of Privacy Professionals, Portsmouth, NH. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://iapp.org/media/pdf/resource_center/DPA-Budget-Staffing-Whitepaper-FINAL.pdf

Gellman, B. (2021). Fair Information Practices: A Basic History. Retrieved 11 18, 2021, from https://bobgellman.com/rg-docs/rg-FIPShistory.pdf

Greenleaf, G. (2019). Global tables of data privacy laws and bills (6th Ed January 2019). SSRN. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3380794

Greenleaf, G., & Cottier, B. (2020). 2020 ends a decade of 62 new data privacy laws. Privacy Laws & Business International, 163, 24-26. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572611

Hammer, C., Kaushik, S., Hwa Song, S., & Ricketts, L. (2021). Putting data and innovation to work for the SDGs: The Data Innovation Fund. World Bank Data Blog. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/putting-data-and-innovation-work-sdgs-data-innovation-fund

Hardinges, J., Wells, P., Blandford, A., Tennison, J., & Scott, A. (2019). Data Trusts: Lessons from Three Pilots. Open Data Institute, London. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://theodi.org/article/odi-data-trusts-report/

Levite, A., & Kalwani, G. (2020). Cloud Governance Challenges: A Survey of Policy and Regulatory Issues. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, DC. Retrieved 11 22, 2021, from https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/11/09/cloud-governance-challenges- survey-of-policy-and-regulatory-issues-pub-83124

McCann, D., Patel, O., & Ruiz, J. (2020). The Cost of Data Inadequacy. New Economics

Foundation/UCL Europe Institute, London. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://neweconomics.org/2020/11/the-cost-of-data-inadequacy

Medine, D., & Murthy, G. (2020). Making Data Work for the Poor: New Approaches to Data Protection and Privacy. Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, Washington, DC. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020_01_Focus_Note_Making_Data_Work_for_Poor_0.pdf

Moerel, L., & Prins, C. (2016). Privacy for the homo digitalis: Proposal for a new regulatory framework for data protection in the light of big data and the Internet of Things. Cybersecurity. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2784123

Mungan, M. (2019). Seven Costs of Data Regulation Uncertainty. Data Catalyst, Washington, DC. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://datacatalyst.org/reports/seven-costs-of-data- regulation-uncertainty/

Pisa, M., & Nwankwo, U. (2021). Are Current Models of Data Protection Fit for Purpose? Understanding the Consequences for Economic Development. Center for Global Development, Washington, DC. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from /publication/are-current-models-data-protection-fit-purpose-understanding-consequences-economic

Pisa, M., Dixon, P., Ndulu, B., & Nwankwo, U. (2020). Governing Data for Development: Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities. In CGD Policy Paper. Center for Global Development, Washington, DC. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from /sites/default/files/governing-data-development-trends-challenges-and-opportunities.pdf

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), Official Journal of the European Union L 119/1, p. 19 - 20

Selinger, E., & Hartzog, W. (2020). The inconsentability of facial surveillance. Loyola Law Review, 66. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3557508

Tisné, M., & Schaake, M. (2020). The Data Delusion: Protecting Individual Data is Not Enough When the Harm is Collective. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/the_data_delusion_formatted-v3.pdf

UNCTAD. (2013). Information Economy Report 2013 - The Cloud Economy and Developing Countries. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Geneva. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ier2013_en.pdf

UNCTAD. (2020). Data Protection and Privacy Legislation Worldwide (webpage). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Geneva. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://unctad.org/page/data-protection-and-privacy-legislation-worldwide

UNCTAD. (2021). Digital Economy Report 2021 - Cross-border Data Flows and Development: For Whom the Data Flow. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Geneva. Retrieved 10 19, 2021, from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/der2021_overview_en_0.pdf

Voss , A. (2021). Fixing the GDPR: Towards Version 2.0. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://www.axel-voss-europa.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/GDPR-2.0-ENG.pdf

World Bank. (2021). World Development Report 2021: Data for Better Lives. World Bank, Washington, DC. doi: https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1600-0

World Economic Forum. (2019). Data Collaboration for the Common Good: Enabling Trust and Innovation Through Public-Private Partnerships. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Data_Collaboration_for_the_Common_Good.pdf

Wylie, B., & McDonald, S. (2018). What Is a data trust? Centre for International Governance. Retrieved 11 03, 2021, from https://www.cigionline.org/articles/what-data-trust/

Appendix

Working Group Co-Chairs

Pam Dixon, World Privacy Forum

Benno Ndulu (in memoriam), Oxford University (Former Central Bank Governor of Tanzania)

Working Group Members

Adedeji Adeniran, Center for the Study of Economies of Africa (CSEA)

Teki Akuetteh Falconer, Africa Digital Rights Hub

Shaida Badiee, Open Data Watch

Donatien Beguy, United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat)

Stephen Chacha, Tanzania Data Lab

Somsak Chunharas, National Health Foundation (Thailand)

Vyjayanti Desai, Identification for Development (ID4D), World Bank

Drudeisha Madhub, Data Protection Office of Mauritius

David Medine, Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP)

Santosh K Misra, Government of Tamil Nadu

Tom Orrell, DataReady

Olasupo Oyedepo, African Alliance of Digital Health Networks

Isaac Rutenberg, Center for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law

Omar Seidu, Ghanaian Statistical Service

Rachel Sibande, Data for Development at Digital Impact Alliance (DIAL)

[1] We continue to mourn the loss of Benno Ndulu, who passed away in February 2021. You can read CGD President Masood Ahmed's post remembering his life and contributions here.

[2] Working Group members are listed in the appendix to this note.

[3] For more on efforts to strengthen funding and technical expertise see the work of the Global Partnership on Sustainable Development Data, Open Data Watch, PARIS21 and the World Bank’s Global Data Facility.

[4] The development community’s growing interest in how data is governed is perhaps best exemplified by the World Bank’s 2021 World Development Report “Data for Better Lives,” which calls for a new social contract in which the use and re-use of personal data is governed primarily by a rights-based framework.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.