Women own a large and growing proportion of businesses in Indonesia, estimated at over half of all micro, small, and medium enterprises. However, women’s economic outcomes are not equal to those of men.

The majority of the 22–33 million women who own businesses operate informal, unregistered microenterprises. Women face more financing and business environment constraints than men. Policies based on rigorous evidence of what works for women are needed to unlock women entrepreneurs’ economic potential. That need motivated an impact evaluation of a mobile savings and financial literacy project in East Java, including the baseline survey whose results are reported here.

Baseline evidence from East Java reveals how gender differentiates entrepreneurs’ economic outcomes (income, savings, other economic outcomes) and identifies factors associated with entrepreneurial success

This baseline survey is the largest survey of entrepreneurs in Indonesia to date, reaching a random sample of 4,828 business owners—59% women and 41% men—in 401 villages in East Java.

Economic outcomes for entrepreneurs were compared for women and men matched for relevant characteristics, including education, cognitive ability, risk taking, and business assets (using propensity score matching). Differences between more and less successful entrepreneurs were analyzed for each gender separately, and gender differences in differences were also analyzed for 21 indicators of demographic and business characteristics. Entrepreneurs with reported average monthly business profits above the median were classified as more successful and those with profits at or below the median as less successful.

Basic demographic and educational characteristics of women and men already tip the entrepreneurial scales in favor of men

- Women entrepreneurs are younger and significantly less educated than men. The gender differential favoring men in completion of secondary schooling is wider in the younger age group, 18–35 years (61% for men and 49% for women) than in the older age group, 36–55 years (42% for men and 32% for women).

- Men entrepreneurs reside in larger households (average of 4.80 residents compared with 3.99 for women), which gives them a significant advantage in labor assets for their businesses.

Entrepreneurs’ economic outcomes also differ by gender

- Men report significantly greater business assets than women. The overall gender gap in the total value of business assets favors men by more than 2:1.

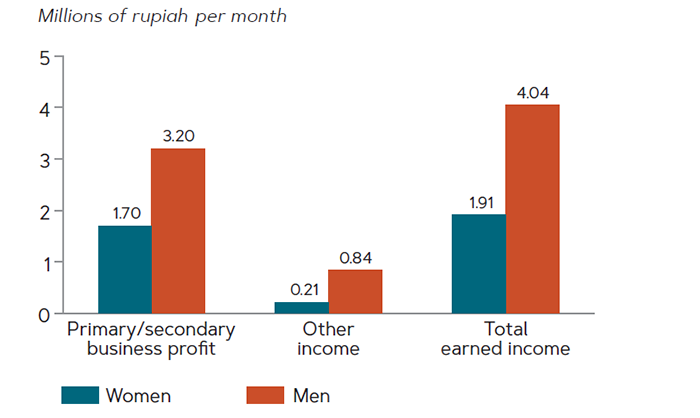

- Women earn significantly less than men from primary businesses (4,825 businesses in all) and secondary businesses (827 businesses) and from other sources of income overall and across business types (figure 1).

- Women’s businesses are highly concentrated in retail, grocery, and food stalls; men’s are more diversified. However, analysis of primary-business profits by type of business and gender suggests that the gender gap in profits would not shrink if women operated businesses in male-dominated sectors.

Figure 1. Among entrepreneurs in East Java, men had significantly higher average monthly profits from all sources than did women, 2017

Note: “Other income” sources include profits from other businesses and wage and salary earnings.

These sharp gender differences in earnings and economic outcomes are only partly explained by differences in characteristics that give men entrepreneurs a head start over women

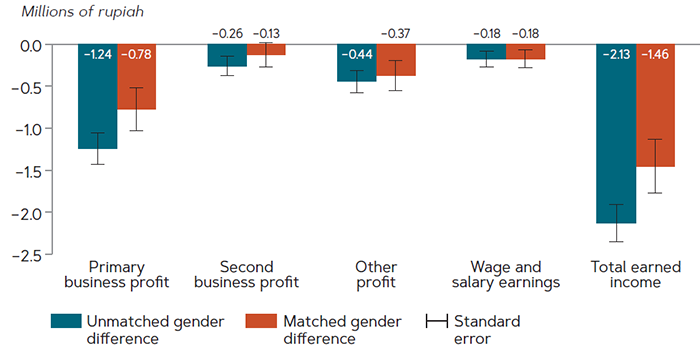

Matching women and men entrepreneurs on characteristics reduces the gender differential in average monthly earned income favoring men by only 32% (figure 2). Other factors (social customs, gender discrimination) likely account for the remaining statistically significant gender differential of almost 1.5 million rupiahs per month in total earned income. As of April 2018, 1 million rupiahs were equivalent to approximately $72.

Figure 2. Matching on gender characteristics reduces by less than one-third gender differentials for entrepreneurs in East Java for three of four sources of monthly earned income, 2017

Note: Gender differentials for “wage and salary earnings” are unchanged and are statistically insignificant for “second business profit.”

Nevertheless, women entrepreneurs are more likely than men to report having any savings and having higher savings as a proportion of earned income

- More women (84%) than men (69%) reported having any savings in a savings instrument in the past 12 months. However, men saved a significant amount more (three times more) than women in formal bank accounts.

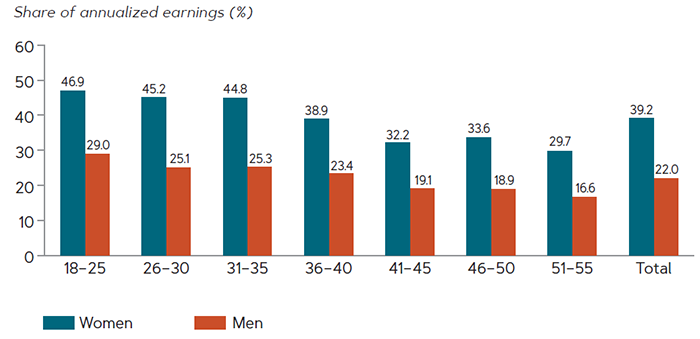

- Women saved significantly more than men in proportion to their reported earned income (saving almost double their income), both overall and in all age groups (figure 3).

Figure 3. Women entrepreneurs in East Java saved significantly more than men as a share of average monthly income overall and in all age groups, 2017

Successful entrepreneurs, both women and men, share characteristics that significantly differentiate them from less successful ones, including:

- Having the business registered.

- Having more business experience.

- Being willing to take risks.

- Having a bank account in one’s name.

- Making high use of savings tools.

- Following recommended business practices.

- Owning a second business.

- Obtaining business help from a spouse.

Leveling the playing field for entrepreneurial ventures requires addressing the social, cultural, and political factors that hold back women entrepreneurs

Differences in entrepreneurial attributes explain less than one-third of the differences in income between men and women, suggesting that legal, business, and financial environments favor men.

Financial institutions should examine their practices for possible biases against women clients in the delivery of financial and other services and take remedial action.

Nonetheless, increasing women’s education and training and improving their business practices are potentially important focuses of policy.

Gender disparities in education persist even in younger age groups, which suggests that less educated young women are becoming entrepreneurs in greater numbers. The fact that good business practices are associated with more successful entrepreneurs supports policy attention to business management training, especially for younger age cohorts.

The ongoing randomized controlled trial that provided the baseline data for this analysis is designed to address both supply- and demand-side constraints on women entrepreneurs’ financial inclusion

The following are two possible demand- and supply-side solutions that inspired this study:

Providing financial literacy to women entrepreneurs to encourage uptake of mobile savings through branchless banking

Overcoming financial service providers’ possible biases against women clients by incentivizing bank agents to enroll more women

The evidence shows that:

- Mobile technology provides women with safe and secure savings and credit services, which may ease mobility, time, and knowledge barriers for women.

- Providing financial literacy training makes the use of mobile savings more effective.

- Incentivizing financial inclusion to target women clients is one way to address potential biases in financial services delivery.

Stay tuned

Connect with us at SheCounts.com to receive updates on the evidence base.

The Center for Global Development is grateful for funding from the ExxonMobil Foundation in support of this work.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.