Recommended

CGD’s COVID-19 Gender and Development Initiative

As donor institutions and governments seek to provide relief and support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and global recession, CGD’s COVID-19 Gender and Development Initiative aims to ensure that their policy and investment decisions equitably benefit women and girls. We seek to support decision-makers in understanding the gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic; assess health, economic, and social policy response measures with a gender lens; and propose evidence-based solutions for an inclusive recovery. Recognizing that the dialogue to date has largely emphasized challenges facing women and girls in high-income settings, our analysis centers on women and girls in low- and middle-income countries.

In this policy brief, we summarize the findings of a CGD working paper, Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment in the COVID-19 Context. We explore the impacts of the crisis on women’s economic opportunities and outcomes, document the extent to which governments and donors are taking action to respond to these impacts, and make recommendations for how decision-makers can elevate women’s economic empowerment as a priority in response and recovery efforts. Specifically, we examine the impact of the COVID-19 global recession on women’s work and employment in low- and middle-income countries, including entrepreneurship, wage and salaried work, work in subsistence and commercial agriculture, and unpaid housework and care work.

What is the problem?

Evidence suggests that the short-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis are similar to past health and economic shocks in causing employment and income losses, loss of revenues for firms and farms, business closures, and increases in household poverty, food insecurity, and unpaid care work. According to International Labour Organization data, the employment loss measured in working hours for women worldwide was 5.0 percent in 2020, versus 3.9 percent for men. The employment-to-population ratio fell 2.6 percent for women, compared to 1.8 percent for men in low-income countries.

We also anticipate similarities in longer-term effects, though evidence will not be available to confirm for some time. These include women’s transition from formal to informal work, transition from cash to subsistence farming, and increased reliance on women’s groups to weather the shock and promote resilience. As the crisis negatively impacts employment outcomes for adult women, younger women and girls witness these impacts and may be discouraged to pursue further education, employment, and other opportunities.

However, diverging from past crises, sectors where women predominate as entrepreneurs and wage workers have been harder hit, and we have yet to observe an “added worker effect” among low-income women to help families cope with loss of household income. Women-owned firms face additional barriers to accessing government support, and are more likely to close, many citing difficulties with managing additional unpaid care work. Facing a lack of income-generating opportunities, women are instead depleting their savings and relying on borrowing to make ends meet.

Preliminary findings are based on limited data, especially for low-income countries and the informal workforce. Data collection efforts in the COVID-19 context are likely to replicate long-standing measurement challenges around women’s paid and unpaid work and add sampling biases linked to the use of phone surveys as the primary collection method, suggesting that the emerging evidence is not capturing adequately the impact of COVID-19 on the poorest women and girls.

What are donors and policymakers doing in response?

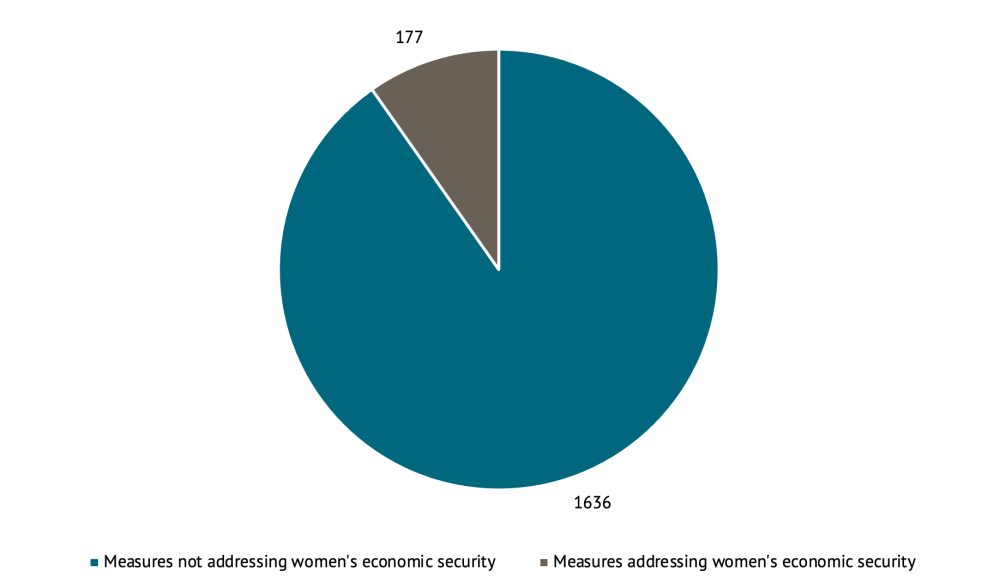

Just over 10 percent of governments’ social protection, labor market, and fiscal and economic policy response measures target women’s economic security. According to data reflected in the COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker, of those labor market measures identified as gender-sensitive, about 70 percent focus on support to enterprises and cooperatives, with fewer focused on job protection, creation, and skills training; digital and financial inclusion; and agriculture. A small subset of labor market measures focus on addressing unpaid care work, but no unpaid care-focused measures are from low-income governments, and just two are from lower-middle-income countries.

Figure 1. Social protection, labor market, and fiscal and economic policy response measures

Source: COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker

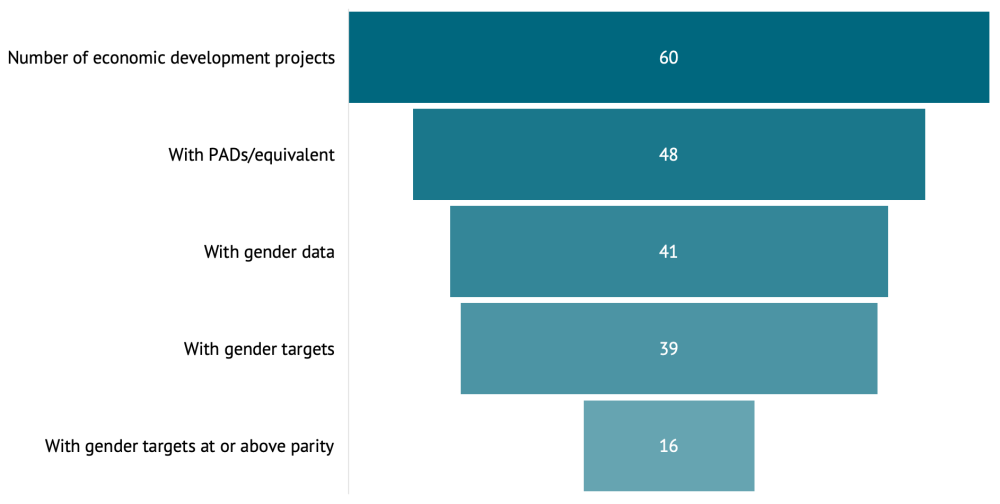

To complement national data, we review project documents from multilateral development banks (MDBs) to gauge the extent to which MDBs are integrating gender into their COVID-19 response efforts. Of 195 projects identified (approved between March and December 2020 by the World Bank, African Development Bank, and Asian Development Bank), 60 projects contain economic response/recovery components (most focus on addressing the pandemic’s direct health effects). Of those with publicly available project documents, 41 projects include gender-focused indicators and 39 include gender-focused targets (though just 16 are at parity). Most (about 60 percent) of projects include gender-focused indicators and targets regarding support to firms, and 44 percent have a focus on job protection, creation, and skills development. Fewer focus on financial and digital inclusion and agriculture, and just one focuses on unpaid care work support.

Figure 2. MDB projects with economic response components, March 1 - December 31, 2020

What else is needed?

Generate more data and evidence

- Fill population data gaps on the gendered impacts of the COVID-19 crisis in low- and middle-income countries, especially for those who cannot be reached by the mobile phone surveys deployed to understand the crisis’s effects. Women and girls lacking access to mobile phones are likely most vulnerable to the risks of extreme poverty and food and shelter insecurity as a result of income loss, but policies and programs designed based on data that excludes them will likely be limited in effectiveness.

- Address longstanding challenges in measuring women’s work, which include undercounting women’s paid activities, especially in informal rural employment and in agriculture, and failing to measure the unpaid care work of women and men. Identifying and agreeing upon a simplified measure (or measures) of women’s economic empowerment that can be used cross-culturally should be a priority. This will enable comparisons of economic empowerment outcomes from recovery measures within and across institutions.

- Monitor and evaluate the benefits of COVID-19 mitigation and recovery measures on women and girls. Good monitoring and evaluation requires good gender data and institutional commitment and openness to track progress, learn lessons, and modify policies and programs if needed. Donors and governments should document successes and challenges they are facing in ensuring that their recovery policies and programs benefit women and girls.

Act using existing data and evidence

- Provide cash assistance and access to saving instruments in the immediate term to individual women and girls (including through savings groups). The extent to which donors and governments have integrated a focus on gender into COVID-19 cash transfer programs and other forms of social assistance is explored through an accompanying working paper on the gendered dimensions of social protection in the COVID-19 context.

- Expand women’s and young women’s access to financial services and ICT—emphasizing reaching the excluded. Expanding individual access to mobile phones, IDs and bank accounts (and reliable lending and saving instruments) is particularly important for empowering women economically. This expansion of access includes both increasing women’s demand for these services and fighting often entrenched biases against women in their supply.

- Strengthen active labor market policies directed at adult and young women, including hard- and soft-skills vocational and business training programs and financial literacy. There is rich evidence on what works (and what does not) to inform the design of these policies and programs, including the use of a “bundled” approach combining asset provision, skills training, and other forms of support when targeting very poor women.

- Provide tailored support to women-owned businesses. Women’s businesses are hard hit because they are heavily concentrated in personal service industries that rely, at least traditionally, on face-to-face interaction. Helping them adapt, including by improving digital access, literacy, and skills, should be a priority both for short-term business survival and long-term business growth. Government grants to help businesses survive long enough to adapt and recover are especially important for women entrepreneurs.

- Similarly, provide tailored interventions to women farmers. The majority of women small and subsistence level farmers working on their own plots or the family farm need a package of bundled interventions, including access to land titles, credit, agricultural markets, technologies and training, to improve their farm productivity and income. Importantly, the supply of agricultural services and products has to target women farmers rather than overlooking them (a commonplace occurrence in the past—and a risk based on our review of donor and policy responses to date).

- Strengthen the care economy. Though evidence is scant on the extent to which care burdens have increased for women and girls in lower-income contexts, care responsibilities are a very real constraint for women entrepreneurs as well as women workers. Public investment in the care economy and fostering of innovative private business models that extend access to care services to more women business owners and households is a critical investment in productivity, and should be a key element of development agendas aimed at “building back better” through inclusive recovery efforts.

- Support women’s groups and networks. Women’s groups can play an important role in promoting resilience and providing support during times of crisis and more broadly, but more evidence is needed to document the impacts that women’s groups are having in the COVID-19 context and how donors and governments can best support them.

This brief is based on the CGD working paper Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment in the COVID-19 Context. To read the full paper, including citations, please visit cgdev.org/covidandgender.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.