Recommended

As Europe’s working-age population continues to decline, sub-Saharan Africa’s is rapidly increasing. Many of these new labour market entrants will seek opportunities in Europe, plugging skill gaps and contributing to economies in their countries of destination. To make the most of these movements, the new European Commission should

- create and promote new kinds of legal labour migration pathways with more tangible benefits to countries of origin and destination;

- pilot and scale Global Skill Partnership projects between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa and within Africa; and

- be a positive voice for migration within Europe, promoting the benefits from migration and ensuring they are understood.

The Challenge

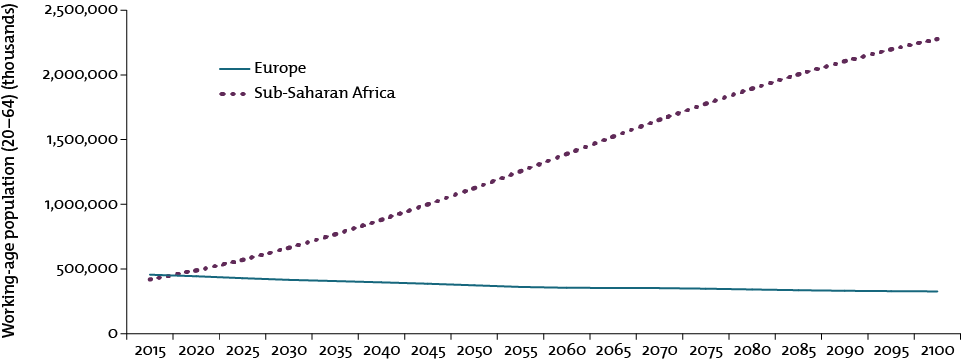

Europe is experiencing significant demographic shifts. By 2100, its working-age population is projected to decline by almost 30 percent from 2015 levels (see figure 1) owing to a combination of low birth rates and increased longevity. The impact of this shift is already being felt as the private sector in many countries demands an increase in the number of workers available and the types of skills they possess. If Europe is to continue to grow and sustain its current social programmes, it will need a substantial increase in the number and type of potential workers.[1]

At the same time, the working-age population in sub-Saharan Africa is booming. This results from a significant development achievement: the reduction in the under-five mortality rate.[2] Many of these new labour market entrants will join increasingly developed local economies, while others will migrate regionally in search of opportunities. Still others will seek work elsewhere, in places such as Europe, to pursue fulfilling livelihoods and send remittances back home.

Figure 1. Europe’s working-age population will continue to decline

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) Population Division World Population Prospects (2017).

Note: This projection uses the “medium-variant,” which assumes a continuation of recent levels of net migration (the difference between the number of immigrants and the number of emigrants for a given country or group of countries). For more information, see UNDESA (2017) “World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables,” “Population Facts.”

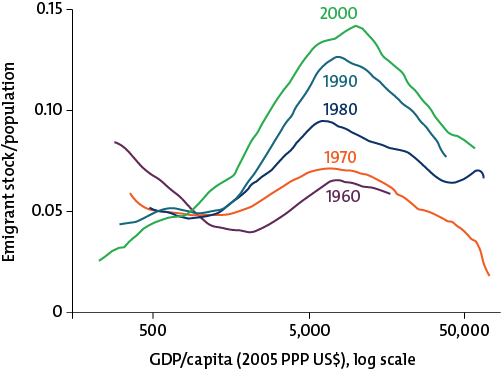

The relationship between migration and development is supported by a wealth of evidence, namely, that development can increase migration (see figure 2).[3] As people’s incomes rise, they gain both the financial means and the aspiration to move for better work, wages, and educational opportunities. In moving, migrants increase their income and knowledge, allowing them to spend more on meeting their basic needs and making future investments. In countries of origin, migration can lead to increased wages and greater economic growth through higher incomes, increased remittances, spending, knowledge and technology transfer, and investment by migrant households. In countries of destination, migrants can fill labour gaps and contribute to services, taxes, and social security systems.[4] In this way, migration and development are inherently linked—increased emigration can reflect, and be a vehicle for, increased development. And in a stable context over time, development will create enough economic growth to push the community past the curve to the point where migration pressures decrease.[5]

Figure 2. To a point, development and emigration go hand in hand

Source: World Bank data quoted in Clemens, M. (2014) “Does Development Reduce Migration?” Center for Global Development Working Paper 359.

Of course, most African migrants stay within the African region, and the number of those moving regionally is increasing faster than the number moving internationally.[6] But if Europe wants to harness the potential of those moving to its shores, and ensure this movement contributes to the growth of all involved, it needs to facilitate new legal labour migration pathways.

The European Union’s Added Value and its Progress to Date

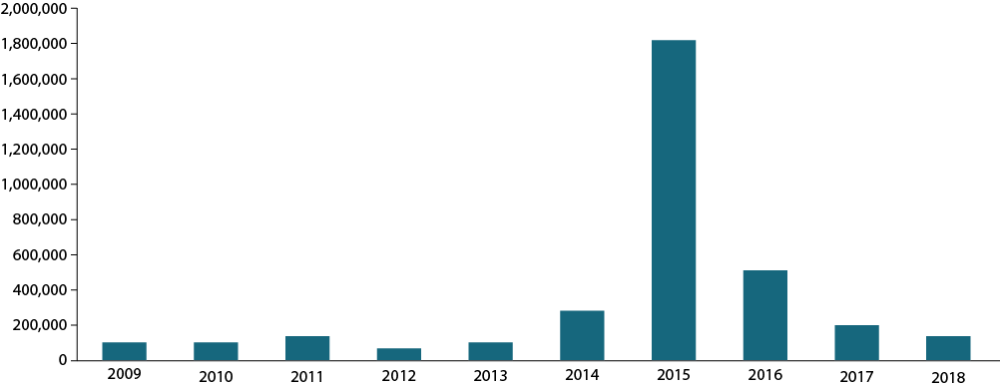

In May 2015, the European Commission presented the comprehensive European Agenda on Migration.[7] It was designed to immediately respond to the 2015 refugee “crisis” through four pillars, aimed at better managing migration over the medium- and long-term. Under these pillars, the Commission has achieved much—increasing refugee resettlement numbers, supporting Member States with border management, financing integration projects, combatting smuggling networks, fighting trafficking, and working broadly on development and security efforts in countries of origin through the European Union Trust Funds.[8] In so doing, the Commission has achieved numerous successes, including reducing the level of irregular arrivals (see figure 3).

However, given the demographic projections detailed above and other forces beyond the Commission’s control—foreign wars, displacement, and climate change, among others—future success is not guaranteed. Furthermore, the Commission’s successes to date largely depend on the cooperation of third states, which may not be assured moving forward. And with no broad European consensus on how to best manage migration, European states too often depend on ad hoc solutions.

The Commission has acknowledged that while both development and border controls are necessary, they are insufficient to curb irregular migration. To reduce the incentives for irregular migration, attract the right set of talent and skills to Europe, and enable admissions to be tailored to the needs of the labour market, Europe needs new kinds of legal pathways for migrants.[9] Without these pathways, the EU’s economic growth will suffer. Accordingly, promoting new legal pathways is the fourth pillar of the European Agenda on Migration. These pathways take three forms: attracting new talent, the Blue Card Directive,[10] and European-coordinated pilot projects. These measures reflect the Commission’s limited room to manoeuvre as Member States retain the right to determine volumes of admission for people coming from third countries to seek work.

The Commission launched the idea of legal migration pilot projects in 2017 in order to “replace irregular migratory flows with safe, orderly and well-managed legal migration pathways; and to incentivise cooperation on issues such as prevention of irregular migration, readmission and return of irregular migrants.”[11] The following year, the Commission published the “Concept Note on the Pilot Projects on Legal Migration.”[12] It listed the target countries, described the application process, and identified the funding streams.[13] One such stream was the Mobility Partnerships Facility (MPF), a flexible and quick-reaction mechanism funded by the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs.[14]

Figure 3. The number of irregular border crossings into Europe has fallen since 2015

Source: FRONTEX (European Border and Coast Guard Agency), updated November 6, 2018.

Four Member States applied to the MPF for funding, including the Belgian Development Agency, Enabel. Its “Pilot Project Addressing Labour Shortages Through Innovative Labour Migration Models” is directly applying the Global Skill Partnership model, training information and communications technology (ICT) workers for employment in Morocco and Flanders.[15] While it is too early to evaluate the pilot’s impact, all actors involved have reiterated the need for such a project to meet demand on both sides. All pilot projects funded by the MPF are investing in skills and human capacity (the latter, for example, through training or internship programmes delivered in European Member States).

What Should the New Commission Do?

The Case for a Global Skill Partnership

Decisions about the number and type of labour migrants admitted across national borders is the exclusive competence of Member States. The Commission cannot propose a “common migration policy” along the lines of its Common European Asylum System. However, it does have an important role to play in promoting, facilitating, and supporting the creation of new kinds of legal labour migration pathways across Europe.

A Global Skill Partnership is such a pathway.[16] It is a bilateral agreement between equal partners. The country of destination agrees to provide technology and finance to train potential migrants with targeted skills in the country of origin, prior to migration, and receives migrants with precisely the skills they need to integrate and contribute best upon arrival. The country of origin agrees to provide that training and gets support for the training of non-migrants too—increasing rather than draining human capital.

For example, both Morocco and the Flanders region of Belgium have identified a shortage of trained ICT workers. Belgium has agreed to finance and support the training of ICT workers in Morocco, some of whom will stay and contribute to the Moroccan labour market. Others will move to Flanders to take up contracts with Belgian companies. This latter group will also receive language and integration training and be connected to local diaspora networks once they arrive.

Six traits distinguish Global Skill Partnerships from existing related policies. Global Skill Partnerships:

- Manage future migration pressure, addressing many legitimate concerns about migration in countries of destination (such as integration and fiscal impact) and in countries of origin (such as skills drain).

- Directly involve employers in the country of destination to identify and train for specific skills they need that can be learned relatively quickly.

- Form a public-private partnership for semi-skilled work—jobs that take between several months and three years to learn and do not require a university degree.

- Create skills before migration, with cost savings to the country of destination and spillover benefits from training centres in the country of origin.

- Promote development by bundling training for migrants with training for non-migrants in the country of origin, according to the differing needs of each. Such training occurs in two tracks: a “home” track for non-migrants, and an “away” track for migrants. Trainees can pick which track to go down—those who choose to migrate could also receive additional training in soft skills, for example in different languages or other facets of integration.

- Are highly flexible. Any agreement can, and must, be adapted to the specific country needs in both destination and origin.

Who benefits from such a model? Effectively, everyone involved.

Europe, in containing countries of destination, receives migrants with the skills to contribute to the maximum extent and integrate quickly, without being a net drain on fiscal or human resources. They can regulate how migration happens, and on what terms, choosing those migrants who fit a specific skills profile and who can contribute and integrate quickly. Countries of destination therefore benefit in four ways: (1) addressing their own demographic change, (2) accomplishing development objectives, (3) increasing migrant integration, and (4) contributing to deterring irregular flows.

The country of origin gets new technology and training facilities, an increase in human capital from those who stay, the prospect of remittances from those who leave, and a reduction in pressure to absorb new labour market entrants.

Those who are trained can migrate regularly and safely or stay and enter the local labour market with better skills. All have their earning potential increased, with flow on benefits.

And everyone else benefits from having skills gaps filled, including those with secondary jobs who rely on those roles being occupied, and those who will occupy new jobs created by those who move and stay.

Creating new kinds of legal labour migration pathways is, of course, a difficult task in today’s political climate. A growing number of politicians advocate for closing national borders and reducing immigrant populations. However, we believe that the Global Skill Partnership model is likely to gain traction among even the more conservative Member States for the following reasons:

- The number of migrants admitted is small and therefore unlikely to attract much political attention;

- Migrants have been selected and brought to the country of destination to meet specific skills needs that locals are unable to meet, and have already been provided with language and integration training;

- The potential migrants will be screened and vetted before they enter the country of destination and easily tracked after they arrive, thereby satisfying security concerns;

- The model meets the desire among countries of destination to participate in the “development” of countries of origin; and

- It provides countries of destination with a practical and pragmatic way to control some migration flows and shift irregular flows into regular pathways, thereby satisfying voter demand for a “managed” immigration policy.

Policy Recommendations

The scale of the demographic shifts highlighted above means Europe cannot wait until migration flows visibly increase to implement a Global Skill Partnership. This tool should be tested now, in a period of relative manageability, before the scale and pace of migration makes innovation difficult. We therefore believe this is a perfect time for the new Commission to expand the scale and scope of such legal labour migration pilots, testing new ways to ensure that migration benefits all involved. Specifically, the new Commission should:

-

Create and promote new kinds of legal labour migration pathways with more tangible benefits to countries of origin and destination. Such efforts can complement existing development and security efforts within sub-Saharan and North Africa, reducing demand for irregular pathways and putting more control in the hands of Member States. The Commission has already established the building blocks for such efforts. The fourth pillar of the European Agenda on Migration provides a framework under which to create and promote new kinds of legal pathways, and existing trade relationships with sub-Saharan Africa provide mechanisms upon which to base discussions. The Commission can support Member States by providing them with the tools, coordination mechanisms, and guidance to implement new kinds of legal pathways. We echo the findings of the recent “Legal Migration Fitness Check,” which calls on the Commission to harmonise conditions, procedures, and rights to overcome fragmentation within the system.[17]

-

Pilot and scale Global Skill Partnership projects between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. A Global Skill Partnership is a tool to manage migration, displace irregular migration flows, shape the terms on which migration happens, and ensure migrants arrive with precisely the skills European destinations need. It is also a development tool in the country of origin, building sustainable institutions that create human capital and build capacity. As discussed above, the Commission is already supporting similar projects and should continue to do so by expanding and diversifying the financing and support available to the MPF and by promoting the opportunity to Member States based on their current and emerging needs and priorities. The Commission should also learn from the experiences of similar projects, such as that being implemented between Germany and Kosovo in the construction industry.[18]

-

Pilot Global Skill Partnership projects within Africa. Many sub-Saharan Africans will not want to travel to Europe, preferring instead to seek work within their region. The Commission can finance partnerships between a country of origin (say, a developing sub-Saharan African country such as Niger) and a country of destination (say, a more developed North African country such as Tunisia). Such a partnership could build necessary institutions and complementary skill sets among native and foreign workers in the country of destination, such as basic construction skills among Nigeriens and middle-management skills among Tunisians. This creates a complementary workforce that helps alleviate pressures on both countries.

-

Be a positive voice for migration within Europe. Such efforts will require an increase in financing, in coordination, in partnerships, and—most importantly—in leadership. We highlight here the many benefits that migration can bring if properly managed, and propose a model to realise these benefits. However, such efforts will require political will and commitment on the part of Member States and a supportive public narrative across Europe. It is imperative that the Commission remains an outspoken advocate for labour migration (and its necessity given the demographic shifts already underway) and showcase positive outcomes from the pilot projects. We have a real opportunity to facilitate new types of migration, but only if the Commission spearheads these efforts.

[1] Pritchett, L. (2015) “Europe’s Refugee Crisis Hides a Bigger Problem,” Center for Global Development blog, www.cgdev.org/blog/europe-refugee-crisis-hides-bigger-problem.

[2] UNICEF (2018) “Under-Five Mortality Rate Data,” https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/under-five-mortality.

[3] Clemens, M. (2014) “Does Development Reduce Migration?” CGD Working Paper 359, www.cgdev.org/publication/does-development-reduce-migration-working-paper-359.

[4] Foresti, M., Hagen-Zanker, J., and Dempster, H. (2018) “Migration and Development: How Human Mobility Can Help Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals,” Overseas Development Institute, www.odi.org/publications/10913-migration-and-2030-agenda-sustainable-development.

[5] Clemens, M. and Gough, K. (2019) “Unpacking the Relationship between Migration and Development to Help Policymakers Address Africa-Europe Migration,” Center for Global Development blog, www.cgdev.org/blog/unpacking-relationship-between-migration-and-development-help-policymakers-address-africa.

[6] McAuliffe, M. and Kitimbo, A. (June 7, 2018) “African Migration: What the Numbers Really Tell Us,” World Economic Forum blog, www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/06/heres-the-truth-about-african-migration.

[7] European Commission (2015) “European Agenda on Migration,” https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration_en.

[8] European Commission (2019) “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council: Progress Report on the Implementation of the European Agenda on Migration,” https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20190306_com-2019-126-report_en.pdf.

[9] Luyten, K. and González Diaz, S. (2019) “Legal Migration to the EU,” European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing, www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/635559/EPRS_BRI(2019)635559_EN.pdf

[10] The Blue Card Directive governs the conditions for entry and residence of highly qualified third-country workers in the European Union. Due to low take-up, reforms to the Directive were proposed in 2016 but have not yet been enacted.

[11] European Commission (2018) “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council: Managing migration in all its aspects: progress under the European Agenda on Migration,” https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20181204_com-2018-798-communication_en.pdf.

[12] International Center for Migration Policy Development (2018) “Concept Note: Pilot Projects Legal Migration,” www.icmpd.org/fileadmin/user_upload/DOC6_Concept_Note.pdf.

[13] The EU Trust Fund for Africa, North Africa Window, provides funding for a regional project in North Africa, carried out by GIZ, the International Organization for Migration, and the International Labour Organization.

[14] The MPF is coordinated by the International Center for Migration Policy Development under the leadership of the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs (DG HOME). The Steering Committee also includes representatives from the Directorates-General Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR) and International Cooperation and Development (DG DEVCO) and the European External Action Service (EEAS). It was originally provided €5.5 million for 35 months (from January 2016). New funding was then granted to rapidly support the pilot projects. The MPF now has another €12.5 million for 36 months (from January 2018). A new phase will start in autumn 2019. Funding comes from the Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund; the Internal Security Fund for Police Cooperation; and the Internal Security Fund for Borders and Visa.

[15] For more information, see the Pilot Project Addressing Labour Shortages Through Innovative Labour Migration Models page on the Enabel website: www.enabel.be/content/europees-proefproject-palim-linkt-it-ontwikkeling-marokko-aan-knelpuntberoepen-vlaanderen-0.

[16] The Global Skill Partnership idea is backed by peer-reviewed academic research including Clemens, M. (2015) “Global Skill Partnerships: A Proposal for Technical Training in a Mobile World,” IZA Journal of Labor Policy; and Clemens, M. and Gough, K. (2018) “A Tool to Implement the Global Compact for Migration: Ten Key Steps for Building Global Skill Partnerships,” Center for Global Development. For more information, see www.cgdev.org/gsp.

[17] European Commission (2019) “Commission Staff Working Document: Executive Summary of the Fitness Check on EU Legislation on Legal Migration,” https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/legal-migration/fitness-check_en.

[18] Clemens, M., Dempster, H., and Gough, K. (2019) “Maximizing the Shared Benefits of Legal Migration Pathways: Lessons from Germany’s Skills Partnerships,” Center for Global Development Policy Paper 150, www.cgdev.org/publication/maximizing-shared-benefits-legal-migration-pathways.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.