Recommended

Blog Post

It’s time we recognized the truth about the future of work in Africa: it isn’t in the growth of full-time formal sector jobs. The future of work will be people working multiple gigs with “somewhat formal” entities. This is already true, and it will be for the foreseeable future. When we consider the future of work in Africa the question shouldn’t be whether jobs will be formal or informal, but how digital platforms and new technologies might make this type of work more productive and of a better quality for workers themselves.

When we plan for the future of e-commerce, technology, and employment, we need to improve the working conditions of independent workers, rather than continuing to pretend that regular, formal, contracted employment is the way that people want (or even should want) to earn a living. The informal sector has been the main driver of employment growth in Africa for decades, absorbing rising urban populations. While this sector is unproductive and lacks employee protections, we need to recognize that realistically, it’s where Africa’s youth bulge is going to find their livelihoods.

African governments face a challenge: finding creative ways for gig workers to gain from the improvements in efficiency and productivity that digital platforms create, and accommodating the progressive inclusion of informal enterprise in the formal economy to generate value for all parties.

The informal sector is resilient but unproductive

When we talk about job losses and gains in the developed world, we are generally thinking of formal sector jobs with regular hours, regular pay, various legal protections, and registered for income taxes. But in most of Africa the situation is completely different: almost all workers are in the informal sector, whether in agriculture or informal manufacturing and services. Those who can work, must, as the state social safety net barely exists.

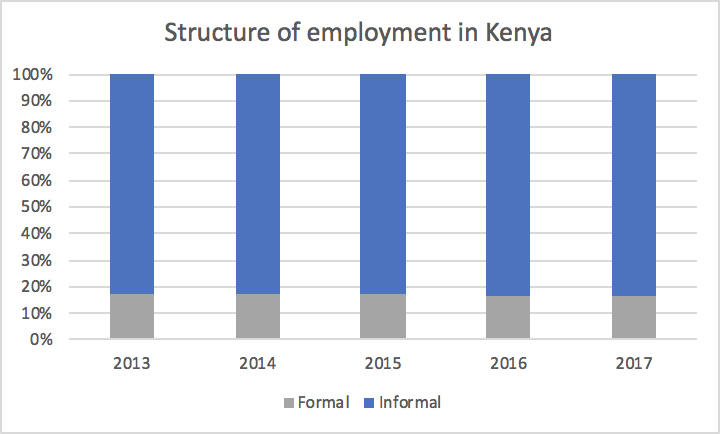

Formal employment has remained a stable share of the economy for years—around 17 percent of employment in Kenya every year since 2012, for example—and perhaps for decades before that (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Formal employment has barely budged over the past five years

Source: Kenya Economic Survey 2018

Kenya is not exceptional. The International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that more than 80 percent of youth in their eight African school-to-work transition surveys were engaged in the informal sector. The ILO surveys also indicate that whereas the formal workforce is mostly male, informal sector entrepreneurs and employees are more likely to be female (and in fact, women are a majority in some countries, like Kenya). Just over half of informal sector workers are self-employed; a small share are employers and a large minority are employees. The main African exception is South Africa, where the informal sector engages merely 17 percent of workers.

Why does the informal sector have such a bad reputation, despite employing so many people and representing such a substantial share of the economy? There are two main reasons.

First, productivity in the informal sector is low. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the formal sector in African countries is much more productive, producing four to five times the per-worker output of informal firms. This translates to low incomes for informal sector workers, a lack of capital for investment, and little contribution to economic activity.

Second, there are no legal protections for informal sector workers—there is no minimum wage, and no requirements around working hours, safety, benefits, or registration for government programs like health insurance or pensions. Neither the informal enterprise nor the informal worker pays income taxes, although they often pay for other fees, licenses, and permits.

Yet the informal sector has a great strength: livelihoods are readily available in this sector. Employment in the informal sector has grown over the past decades along with rising populations and accelerating urbanization, and it seems likely to continue. BFA’s Financial Dairies research has shown that the capital required to enter an informal business is negligible (it was only US$7 in the Kenya Diaries), and the losses on exit are also small. Skills requirements are minimal; the informal sector is the main employer of people with less-than-high-school education. Illiteracy has been falling rapidly, but still, the World Bank reports that 25 percent of African youth aged 15-20 could not read in 2016, so the informal sector is a major source of livelihoods for the illiterate and those with educational attainment.

Digital platforms offer a progressive onramp to formalization

Disruption is looming. The rapid automation of both manufacturing and service jobs is replacing formal sector workers in many industries. The World Bank worries that Africa will miss the development opportunity that drove Asia’s export-led industrialization and growth out of poverty; as wages rise, firms are replacing workers not with cheaper labor—as in other countries—but with robots and artificial intelligence (AI), producing cheaper and cheaper goods for distribution in the worldwide e-commerce ecosystem. Service industries could also be at risk as new technologies create scale and consolidation, or bypass the need for the service altogether (e.g., travel agents).

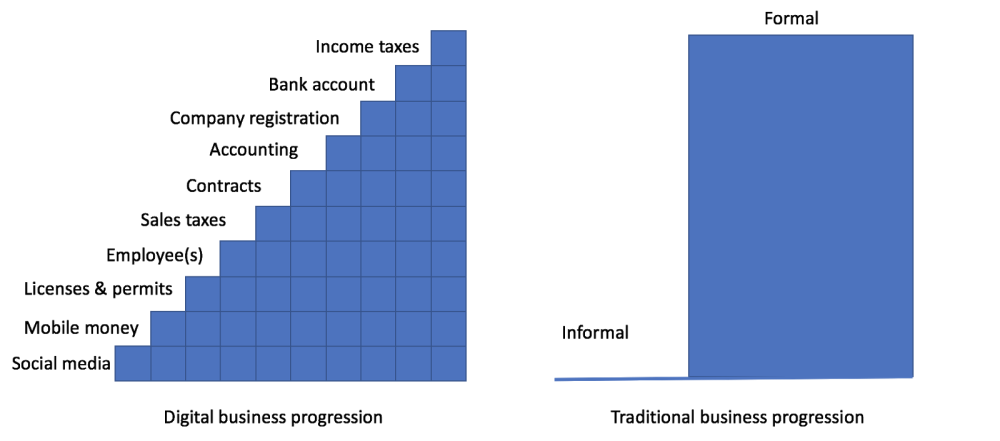

Is this a disaster for Africa? Will the informal sector lose its ability to generate livelihoods as both goods and services become automated? It’s not clear which way the market will swing, but we already see digital platforms starting to change the very nature of what it means to be informal or formal. Until now, enterprises were (more or less) either in the informal sector or in the formal sector. Yet the digital world allows a business to take on formality in small, accessible, low-cost steps that match company needs—more of a ladder to climb than a cliff to scale, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Digital vs. traditional formalization process

We’d expect this digital progression to enable a lot more businesses to successfully make the transition from startup to formal enterprise because each step is at less cost and less risk. Even if a business doesn’t make it to the apex, there is value created at each step.

In addition to their core proposition of matching buyers and sellers, we also see platforms helping enterprises with business services, leaving the enterprise to concentrate on its core competence. Platforms offer advice on how to set prices, training in how to handle customers, ratings to improve incentives for good behavior. Platforms provide accounting and analytics, they offer credit, they collect sales taxes. They handle customer service, payments and returns. This is not unique to Africa, but what is unique is the degree to which these services are needed in Africa; most entrepreneurs have never worked in the formal sector, nor do they have mentors who have created larger businesses. Again, these services probably increase the survival rate and growth path of enterprises and may possibly contribute to growing productivity as these businesses are able to concentrate on their market proposition rather than attending to operational and management issues.

African workers are in gig employment already

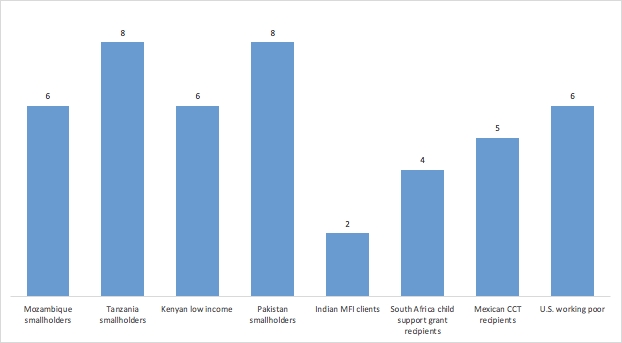

Following dozens of households every two weeks for a year, BFA has conducted financial diaries studies in Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, India, and Mexico. These financial diaries illuminate the lives of people on low incomes, one transaction at a time. What we’ve learned is that they have a lot of income sources in the course of a year, ranging from two in India to eight in rural Tanzania and Pakistan (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Median number of sources of income per household in a year

Source: BFA Financial Diaries

To illustrate how this works: people will do a few weeks of casual labor on a neighbor’s farm, or spend a few days selling sweets during a festival. They’ll try to run a tiny business and often end up closing. They will take in laundry in the evening after their main job is over. They live in the gig economy.

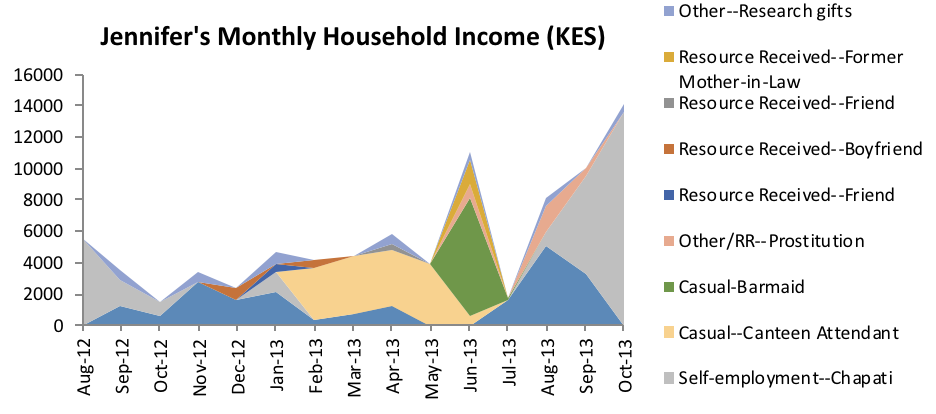

These activities are low income and low productivity and take place mostly in the informal sector (or as casual workers in formal enterprises). Most don’t require any particular skills or knowledge and need minimal investment in stock or tools or assets. Pay is low, hours are long. Income is extremely volatile, fluctuating typically by about 50 percent from month to month (e.g., workers might earn US$750 this month, US$250 the next, and US$500 the following month; see example in Figure 4). There’s no health insurance, no pension, no labor protections.

Figure 4. The many sources and high variability of one household’s income

Actually, people prefer gig work anyway

In our studies, people hated casual labor—the type of work where people line up on the sidewalk and an employer swings by and hires workers for the day or week. Maybe the worker doesn’t get hired at all on any given day.

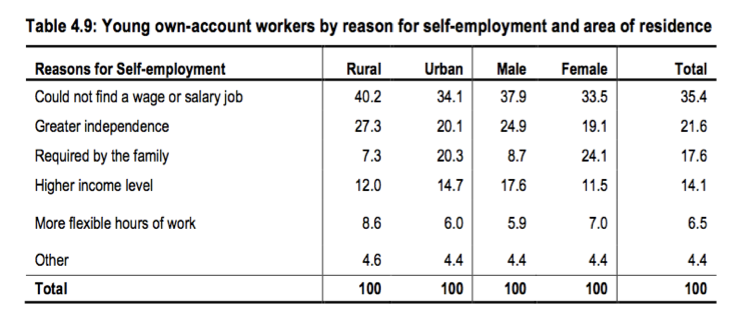

But other work that we consider part of the “gig economy”—project work, skilled work, motorcycle delivery driving, and micro-business—were aspirational livelihoods, even for some people with formal jobs. Workers enjoyed that they got to choose their own hours and didn’t answer to anyone while having the ability to grab an opportunity if they saw it. Other surveys have shown the same results; for example, the ILO school-to-work transition survey shows that only a minority of Ugandan youth felt they were in self-employment out of desperation—the rest had chosen it for independence, flexibility, income, or family reasons (Table 1).

Table 1. Reproduction of ILO table showing multiple factors behind self-employment

Source: International Labour Organization (ILO). Uganda youth transition survey 2016.

Digital platforms will create new gig opportunities

In the short-term, it looks like technology is going to create a set of new opportunities in the gig economy: shared-ride drivers, homestay hosts, e-commerce logistics, e-commerce sellers, and small-scale e-commerce producers. These will be supplemented by an army of “digital translators.” For instance, the Kenyan cellphone company Safaricom employs 5,400 people in its formal business in Kenya, but it has catalyzed the creation of over 130,000 mobile money outlets (which each employ one or two people) to handle the transition from cash to mobile money. The e-commerce platform Jumia employs 3,000 people across Africa, but has signed up 100,000 commission-based affiliates who help customers make orders through the platform. As an economy digitizes, more people are needed to help the customer and the citizen transition into the digital economy. Most of these translators work on commission and set their own hours.

Even where it doesn’t create new industries, technology offers expanded opportunities for traditional gig industries, opening up new markets to artisans (e.g., Lynk in Kenya) and domestic workers (such as Domestly in South Africa). This shift offers sufficient scale for artisanal producers of food, cosmetics, and clothing, and for accelerating regional and international informal trade.

Policy should aid the growth of quality e-commerce livelihoods

So, will the digital world provide enough support to small-scale entrepreneurs that they can survive and grow to the extent of becoming the motors of a new formal(ish) economy in Africa? Early indications suggest modest effects; in July 2018, Jumia Nigeria indicated that 50,000 African merchants across 14 countries were selling on their platform. This is an impressive number, but it compared to a total of 37 million micro-enterprises in Nigeria alone in 2013. Meanwhile what’s the likelihood that these micro-enterprises, even if they went online, will expand and grow? Amazon has about 5 million sellers, and added over 1 million new sellers in 2017, but only about 2 percent make more than US$100,000 in annual sales.

Something more is needed; it may be that new technology allows African businesses to open new expert markets, as Asia has done before. In BFA’s research for the FIBR project, we have seen a surprising degree of cross-border trade using social media and mobile money. Can digital be the accelerator of new regional trade? And will this trade be big enough to create work that is good enough to drive economic growth? Or will African governments have to negotiate new trade agreements that promote African products abroad in exchange for access to local markets for platform providers?

Regardless of the answer, African government should recognize the progressive path of business formalization that e-commerce represents and not penalize but encourage it, to help more businesses survive and grow.

How do we ensure that gig work is good work?

Yet are these digital jobs the jobs we want? Each opportunity is highly competitive, not only within the country but across borders. The Kenyan government online portal claims 40,000 Kenyans are registered on Upwork, where they are competing with English-speaking providers in the Philippines and Jamaica. Small-scale sellers of mass-produced electronic goods must compete with sellers from China to Tanzania. It seems possible the sellers, workers, and providers in the new digital world will compete away any profit, while the rewards go to the platform providers. This next-generation gig economy hardly seems any better than the old one, especially as major international platforms resist providing any of their workers with the protections and benefits of formal enterprises, as well as actively seeking to avoid taxation.

One way to make gig work better would be to recognize it for what it is; neither formal employment nor self-employment, and not one job but a portfolio of different gigs. Seth Harris and Alan Krueger have been advocating for the independent worker in the US, where the formal sector and its protections are far more developed. In African countries, it’s probably realistic to ask governments to recognize that gig work is the main source of livelihoods for most and then mandate that platform providers open their systems to allow workers to register for government benefits and private services rather than creating a whole range of poorly enforced regulations.

Allowing workers to maintain a single identity through the different platforms would be an important way for individuals to carry their reputation, their financial history, and their benefits packages with them as they move from gig to gig. Governments could offer benefits such as health insurance and pensions directly through interfaces in the platforms and could require these platforms to open themselves to private providers as well. This may not be practical at the level of a single small African country, but it is potentially something that regional blocs could negotiate with major platforms.

Another important area where gig work could be improved is the frequency and reliability of payment, including for e-commerce sellers. Most African e-commerce is still on a cash-on-delivery basis due to a trust deficit in these new industries. Meanwhile, gig services vary from regular weekly payments in some cases, to un-supervised payments from buyers that may come late or not at all; many freelance platforms function this way. Escrow and insurance services, which allowed the rapid expansion of marketplaces like eBay and Alibaba, are nascent and not extensively used or understood. Since mobile money (which is instantaneous and transparent) is widely available in many African countries, improving payments in the gig economy seems like low-hanging fruit that governments and the private sector could take on.

Solving the problem of how to push more of the profit to the gig workers seems more challenging. Technology creates efficiencies, and these generate the opportunities for profit, but most of the profit seems to go to the platforms, with only a few aggregators (e.g., entrepreneurs who operate a small fleet of Uber cars) taking the next share. The provider at the end (the Uber driver in this example) is offering an undifferentiated product in a highly competitive market, and it doesn’t seem likely they will end up earning above the locally acceptable minimum wage (not the legal minimum, but the minimum people are willing to be paid).

Barriers to entry (such as restrictions on the numbers of Uber drivers) or minimum wage or price regulations could be one approach, but they reduce the consumer surplus that makes the whole market grow. In addition, they are difficult for governments to understand in such a rapidly changing marketplace.

Taxing the gig economy and then returning the profits in government services is another option, but most African governments can’t be trusted to tax fairly nor to return the profits in the form of useful government services. Nonetheless, if African countries could capture a fair share of taxes from international platforms, that could be an important way for them to fund the measures they will need to take to handle this challenge in the future.

At present we don’t have a good answer to how government should best ensure that platforms give a fair share of the profits to workers; rather the trends seem to be that platforms concentrate the returns to capital and intellectual property. But perhaps African governments will be able to lead the way in policy, starting with a realistic recognition of where the workers are: in the gig economy.

This note is part of a special series authored by members of CGD’s Study Group on Technology, Comparative Advantage, and Development Prospects. Learn more at cgdev.org/future-of-work.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.

More Reading