Recommended

Within donor ecosystems, development finance institutions (DFIs)[1] and bilateral development agencies play different yet complementary roles that ultimately aim at the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[2]Using different financial tools and approaches, these institutions tackle pervasive development challenges through multiple means, where synergies between their actions and activities—particularly as they relate to private sector development—offer the potential for greater development impact. Specifically, such actions can be “mutually reinforcing,” where development agency activities aim to create the conditions that enable long-term market success, while DFIs can help “seed and scale” innovations to support job creation, growth, and transformational change.[3]

Despite these theoretically complementary roles, there remain questions about how well this relationship works in practice. Indeed, while cooperation mechanisms are in place between agencies and DFIs themselves, particularly at the European level, [4] recent analysis has suggested that DFI and development agency alignment is lacking, highlighting a range of challenges—including mismatched incentives, differing capacities, tools, absence of joint programming and divergent ways of working—that typically inhibit cross-actor coordination for development.[5]

In this note, we complement existing research on the cooperation between DFIs and development agencies by analysing the results of a survey which look, for the first time, at this relationship across Development Assistance Committee (DAC) member countries and their national DFIs. The survey gathers first-hand perspectives of how DFIs and development agencies coordinate activities, the challenges they face—and how these challenges differ actors both types of actors—as well as how these barriers could be overcome.

While there is overall satisfaction with regards to the level of cooperation between DFIs and bilateral agencies, we find that DFIs and agencies hold divergent views on the success of their current cooperation efforts. DFI respondents expressed high satisfaction levels while development agencies perceived cooperation to be less effective. This divergence is likely a result of differences in their goals and motivations. The results also clearly demonstrate that current cooperation efforts are primarily limited to knowledge sharing rather than action-oriented strategies tailored to their respective areas of expertise. There are, however, both opportunities and the willingness to strengthen coordination and cooperation systems, with a much stronger focus on strategic planning, and country level operations where DFIs and agencies could work hand-in-glove to generate investment opportunities and structure blended finance operations by bringing together DFI financial expertise and development agency know-how.

Methodology

The analysis presented in this note draws from a survey conducted with senior officials from DAC member DFIs and development agencies, which aimed to gather first-hand perspectives on the challenges facing coordination, and ultimately, cooperation between these actors. Key features of our survey approach include:

- Survey population and sampling: the population for our survey was all 18 DAC member countries with DFIs and the primary agencies responsible for managing development policy and implementation in these country systems.[6] Specifically, we contacted senior officials - who have knowledge of their agency’s activities and were able to speak on their organisations’ behalf—from the DFIs and development agencies of these countries.[7] Potential respondents were identified using a combination of convenience and purposive sampling, which both drew from our available networks as well as utilised desk research to identify relevant counterparts. The survey was administered electronically between May and August 2023.[8]

- Response rate: Out of 18 DAC providers, we received answers from 11 DFIs (61 percent response rate) and 14 from development agencies (74 percent response rate).[9]

- Limitations: Our survey approach is limited in three main ways. First, by targeting senior officials who were able to speak on their agency’s behalf, the total number of responses to our survey is necessarily small. However, the relatively broad coverage of our survey responses and the seniority of our respondents means that the responses provide insights into the challenges facing coordination and cooperation across actors. Second, the limited number of responses and sampling methods mean that our findings reflect perceptions of trends identified by respondents but may not capture the perspectives of others within their organisations, particularly those with differentiated experience (i.e. more or less field experience, etc.). While this is necessarily a limitation, by targeting those with a high-level overview of their organisation’s functioning, we assume that responses capture major barriers to cooperation. Third, we recognize that DAC members’ development agencies and DFIs are not homogenous and differ in terms of their size, instruments, and activities, so may not be directly comparable. Despite such differences, we contend that there is value in mapping and understanding a broad array of challenges faced across DAC members, which will differ based on their individual constraints.

Unpacking cooperation practices, challenges, and improvements between DFIs and development agencies

This section presents the main findings from our survey, following the general flow of the questionnaire. The first part details the current scope of cooperation between DFIs and development agencies, while the second part explores key cooperation challenges across DFIs and development agencies and how these can be overcome.

Underlying this study is the starting assumption that stronger cooperation across DFIs and development agencies is both needed and desirable. Based on the understanding that public funding for development is becoming scarcer at a time when global development challenges are multiplying and magnifying, and the financing gap to achieve the SDGs is growing, leveraging the resources across both actors could deepen results. Indeed, evidence shows that combining capital investment from DFIs and programmes aimed at market shaping by development agencies can have transformational change on targeted sectors.[10]

To test the validity of this assumption, we asked survey participants whether there was value in coordinating development activities between DFIs and development agencies within the same country system. Our results showed that an overwhelming majority—91 percent and 93 percent of DFI and development agency respondents, respectively—answered “yes.” When asked to explain the benefits of coordinating action between DFIs and development agencies, most respondents noted that such coordination can contribute to increasing development impact through strengthening alignment, coherence, and ultimately, the effectiveness of development finance offers.[11] With respondents agreeing that coordination is valuable, the rest of our survey aims to understand both the extent to which such coordination currently occurs, and how it can be improved.

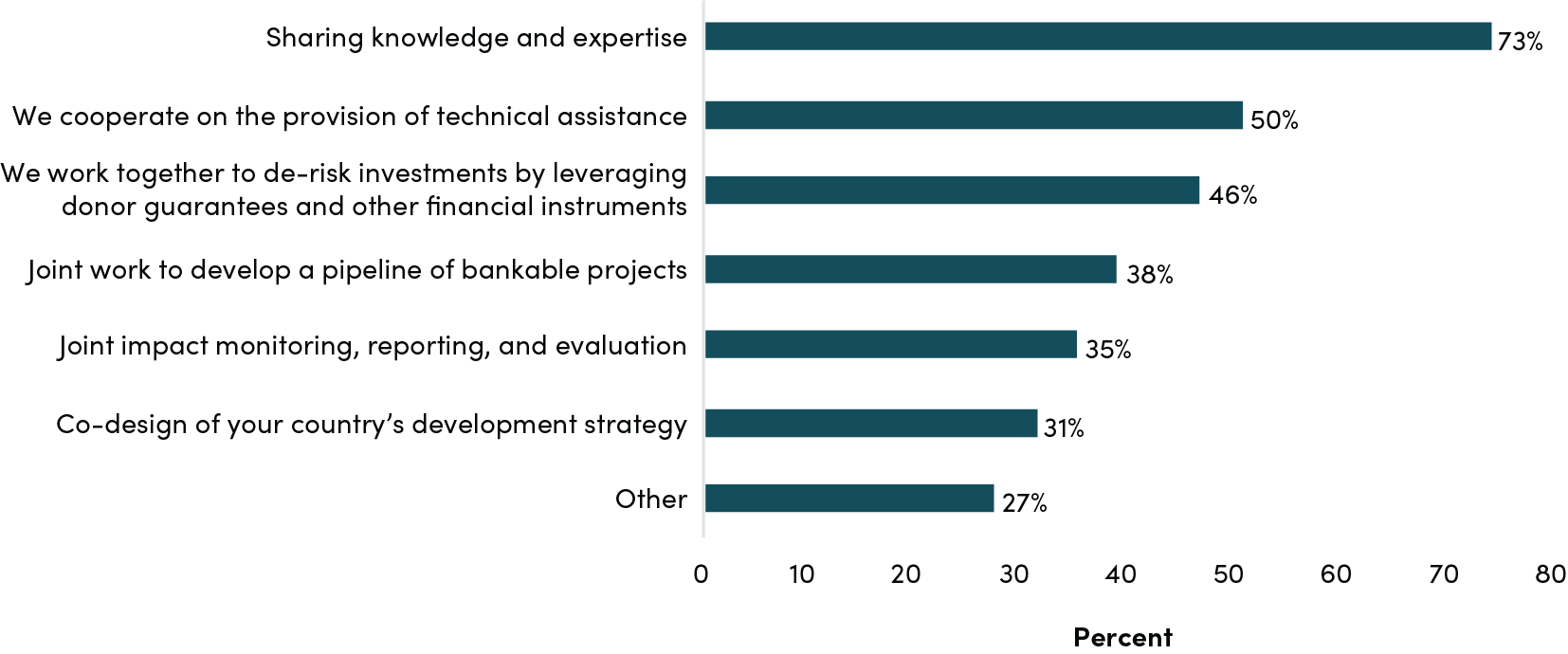

To do so, the early sections of our survey began by asking a series of questions designed to establish a baseline for how, on what, and to what degree, DFIs and development agencies within the same government system, cooperate on development-related action. When asked how their DFIs and development agencies typically cooperate with counterparts from the same government system, 73 percent of respondents identified “sharing knowledge and expertise” (for example, DFI financial engineering expertise and agency knowledge of operating in fragile contexts) as a key form of cooperation, suggesting an ongoing effort to understand and leverage the “different yet complementary” knowledge that exists across agencies.[12] However, other key forms of cooperation—which are more action-oriented—saw lower overall results, with 50 percent of respondents cooperating through the “provision of technical assistance”, and fewer noting engagement to “de-risk investments” (46 percent), as well as to develop a “pipeline of bankable projects” (38 percent). This could be due to the complexities of “doing” development together, which requires deeper engagement with often divergent processes, incentives, and priorities, and overcoming discrepancies in organisational knowledge, where the lack of in-house investment expertise in development agencies, for instance, constitutes an obstacle to cooperation.[13]

Figure 1. How do DFIs and development agencies typically cooperate?

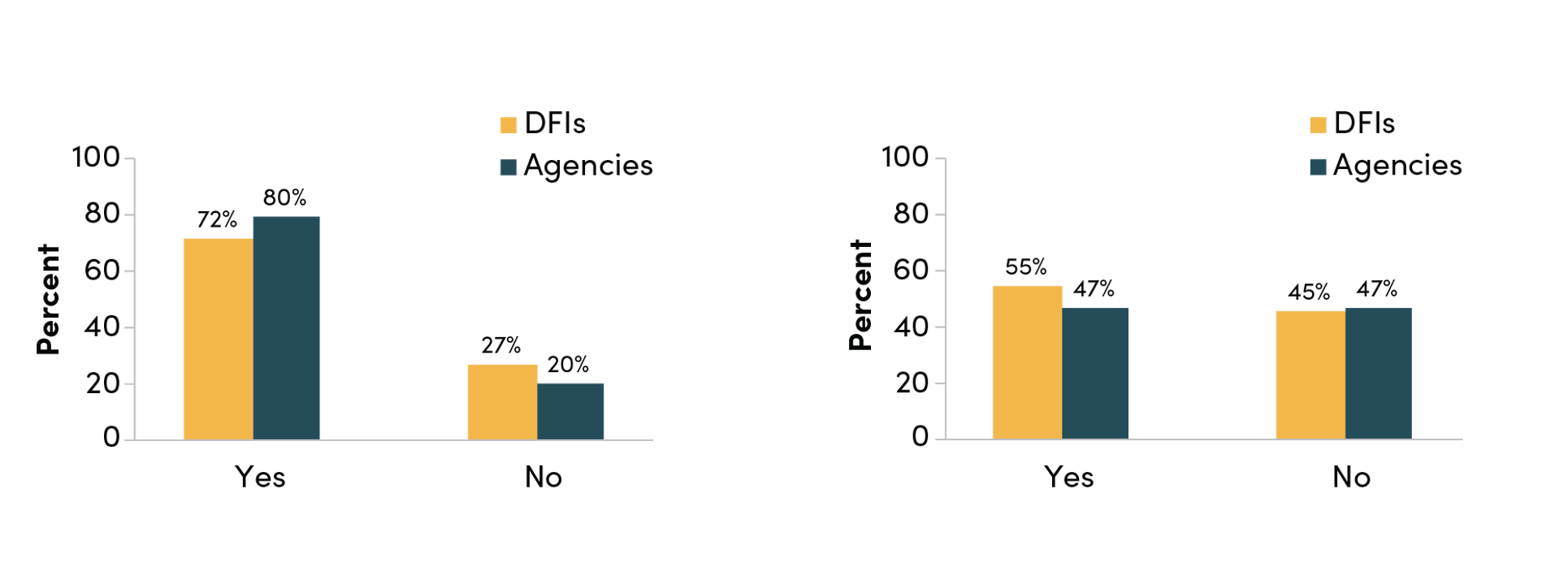

To understand the mechanisms used to support these types of cross-agency working, we asked respondents both whether there were systems in place—such as regular meetings, exchanges of information and planning activities at headquarters and in partner countries—to coordinate their DFI or development agency’s cooperation efforts, as well as how frequently staff engaged to discuss and coordinate action (Figures 2a and 2b). Notably, while the majority of respondents from both types of organisation recognised the presence of such systems at headquarters (72 percent and 80 percent, respectively), roughly half (55 percent for DFIs and 47 percent for agencies) reported having similar systems for collaboration in partner countries. In part, this is likely due to the relatively lower field presence of DFIs, many of which tend to manage operations from headquarters, using staff missions to partner countries when needed.[14]

Figures 2a and 2b. Are there systems in place to coordinate development activities with your country’s DFI or bilateral development agency at headquarters/in partner countries where you both work?

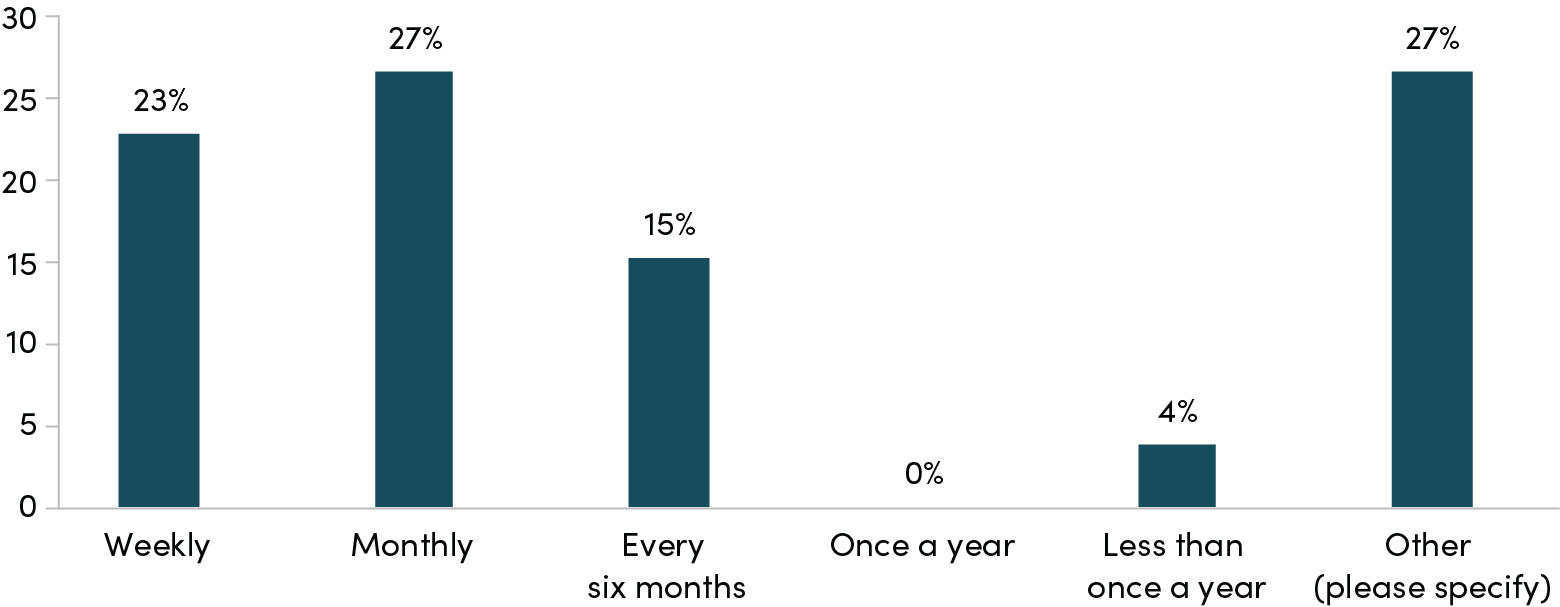

When asked about the frequency of cross-agency discussion, while half of the respondents reported meeting with development agency or DFI counterparts at least once a month (with 23 percent noting weekly meetings and 27 percent reporting monthly engagement), roughly 20 percent noted less regular engagement including meeting only on a bi-annual (15 percent) or annual basis (4 percent) (see Figure 3). The remaining 27 percent selected “other” and specified responses including “quarterly” meetings and “informal and ad hoc” meetings, while one respondent noted differences in the frequency of engagement depending on the level of participants, with working level exchanges occurring regularly at headquarters and in-country, and bi-annually at the senior management level.

Figure 3. How frequently does your agency engage with its development agency/DFI counterpart to discuss development strategy, implementation, or other issues related to development activities?

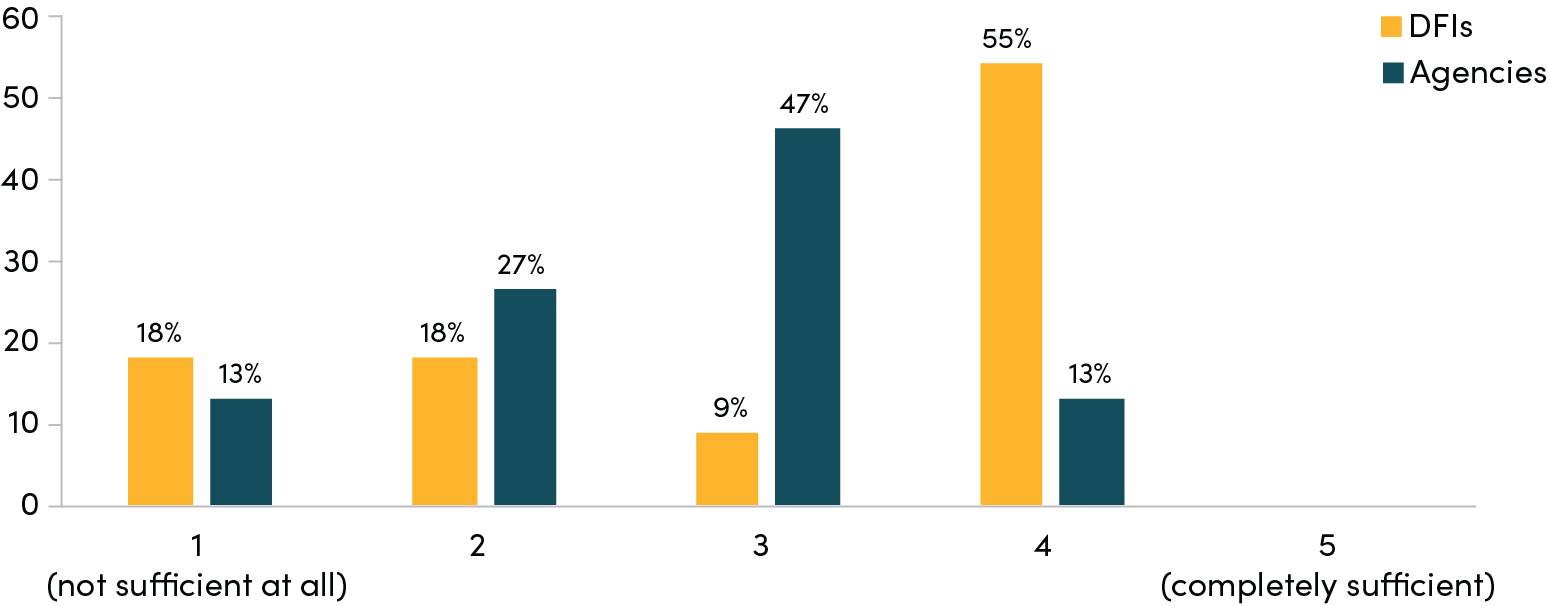

If most cooperation providers have systems in place to coordinate DFI and development agency action – and meet regularly to discuss key issues - then a pertinent question concerns how well these systems function. To answer this question, we asked respondents to rank the sufficiency of their country’s current coordination systems for managing the relationship between DFIs and development agencies on a scale of 1 (not sufficient) to 5 (completely sufficient). The results showed DFIs generally rating coordination systems as more sufficient than development agency counterparts (Figure 4). Most respondents from DFIs (55 percent) gave current coordination systems a score of 4 out of 5 in terms of sufficiency, compared to only 13 percent of development agencies. When asked to explain their responses, those awarding a score of “4” tended to argue that despite differing organisational priorities, joint processes currently allow for synergies and cooperation in country[15] and at the policy level.[16] By contrast, the bulk of development agencies (47 percent) gave current systems a score of 3 out of 5, compared to 9 percent of DFIs. These respondents highlighted a range of ongoing challenges to coordination, including related to mis-matched strategic priorities,[17] lack of staff—or staff capacity—in the field,[18] and difficulties reconciling differing incentives and models of engagement.[19] Moreover, with none of the respondents selecting the highest score (5 out of 5), coordination systems have room for improvement.

Figure 4. In your opinion, are the current systems for coordination development activities between DFIs and development agencies sufficient for achieving synergies to improve development impact? (1 = not sufficient at all; 5 = completely sufficient)

Differing perceptions of how well current coordination systems currently function—with DFIs generally feeling more positive about current processes—were similarly highlighted by respondents when asked whether they faced any challenges in coordinating activities with DFI or agency counterparts. While most respondents answered “yes,” the share of respondents noting challenges was much higher for development agencies (87 percent) than DFIs (55 percent).

To a degree, generally lower perceptions of challenges by DFIs—and higher opinions of the sufficiency of current coordination systems—could be linked to different institutional incentives and missions, which likely inform understandings of the purposes and necessity of coordination in the first instance. For example, the market-based orientation and motivation driving a majority of DFIs[20] could reduce the necessity of coordination, which primarily serves a developmental purpose (i.e., the value of coordination is—in theory—the ability to improve development impact rather than financial returns). Linked to the understanding that DFIs measure “success” through “firm-level performance,”[21] either the absence of coordination, or coordination in a lesser form, is unlikely to prevent or limit DFIs from achieving their primary (profit-driven) aim. By contrast, for development agencies, achieving the transformational and developmental outcomes desired through private sector development activities could benefit more greatly from coordinated actions to utilise private financing instruments to support sector transformation.

With the majority of DFIs and development agencies noting the presence of challenges to coordination—albeit to differing degrees—a key question then becomes one of identifying the specific challenges that both types of agencies face. To better understand the main challenges to coordination between DFIs and development agencies, we presented respondents with a range of potential coordination barriers and asked them to select all that apply (Figure 5). Our results show that both DFIs and development agencies overwhelmingly view having a “limited understanding of each other’s tools and resources” as the most significant limitation (identified by 64 percent of DFIs and 67 percent of agencies), followed closely by “asymmetry in organisational objectives and incentives” (identified by 55 percent of DFIs and 67 percent of agencies), which restricts the overall overlap in where and how both actors work. A fundamental tension between DFIs and development agencies pertains to questions about whether and to what degree DFIs should align development spending with partner country development plans, which (in theory) often serve as the guidepost of development agency action.[22] DFI respondents also noted a lack of local presence as a significant challenge (selected by 55 percent of respondents), while development agencies cited procedural differences across agency as a key barrier to coordination (identified by 53 percent of respondents). More than 25 percent of DFI respondents also noted that they face “no challenges” to coordination; however, it is unclear whether this finding is driven by the absence of barriers to coordination or reduced impetus for coordination in the first instance.

Figure 5. What are the main challenges that DFI and agencies face when coordinating development activities?

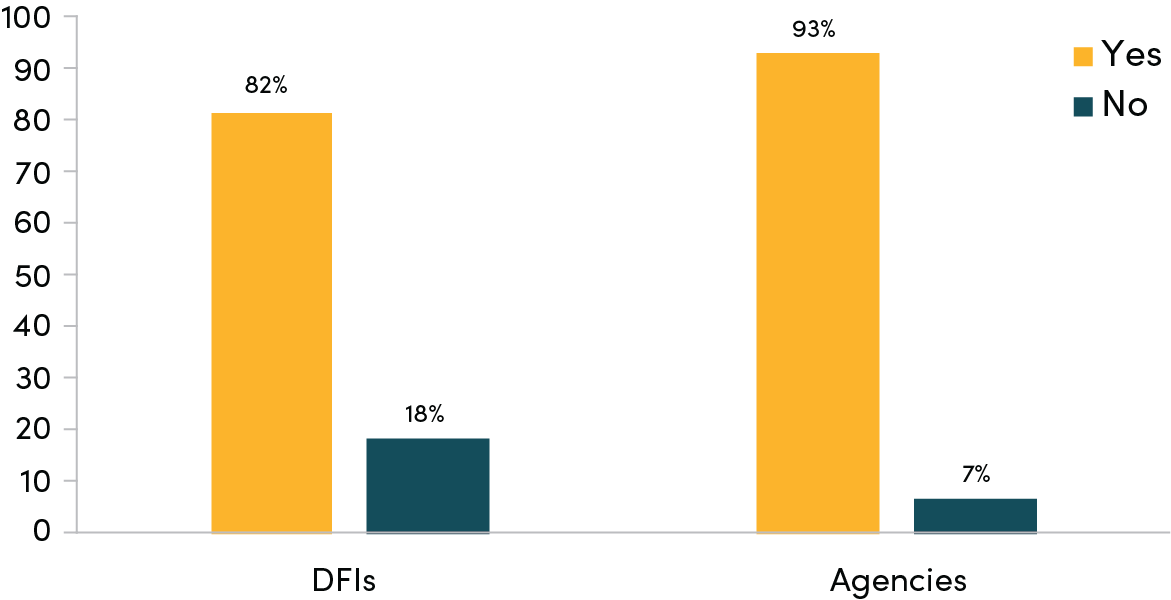

Given clear challenges facing coordination across actors, we asked survey participants whether they believe there is value in investing resources to strengthen coordination between the two entities. Surprisingly, an overwhelming majority of respondents from both DFIs and development agencies (82 percent and 95 percent, respectively) answered “yes” (see Figure 6). However, due to the diverse nature of the challenges faced, many of which are related to fundamental differences in organisational incentives, priorities, and procedures, there are questions about where investment might be best placed to support joint action and improved impact. Hence, several respondents supported the idea of new initiatives designed to understand each other’s approaches and tools with the view of identifying concrete ways DFIs and development agencies can better complement each other. Respondents also pointed out the opportunity for their institutions to invest in policy dialogue, including in partner countries, which will facilitate the identification of complementarities in specific projects and in activities designed to create stronger enabling environments for market transformation.[23]

Figure 6. In your opinion, is there value in investing resources to strengthen coordination between your DFI and your country’s bilateral development agency?

When asked how coordination between DFIs and development agencies could be improved, respondents from both types of organisations frequently highlighted the need for more structured information sharing and learning to improve mutual understanding of each other’s work and create opportunities to identify spaces for collaborative action.[24]Respondents suggested that this could be achieved through more regular communications, including to discuss lessons learned from past engagement, and to explore both the opportunities and limitations of coordination more fully.[25] Others highlighted the importance of strategic-level planning to guide shared action, suggesting that there is a need to improve “line-of-sight” into project pipelines, partly to identify opportunities for coordinated action earlier in the project process.[26] This could allow for greater opportunities to leverage both DFI and development agency skills and experience to support better project outcomes. Similarly, some highlighted the importance of ensuring strategic alignment across DFIs and development agencies, using a clear “action agenda”—if not common strategies—to ground coordination and avoid the potential pitfall of “coordinating for coordination’s sake”,[27] while others stressed the importance of deeper engagement in-country.[28] While there are some examples of coordination platforms towards this end—consider for instance, Nepal Invests, a platform made of DFIs and development agencies to address regulatory challenges and increase financial skills in Nepal in order to attract investments[29]—there remains scope to expand opportunities for such strategic engagement. Lastly, only one respondent noted the need for political leadership to provide an impetus for coordination, potentially suggesting that well-founded institutional incentives for coordination no longer need to be driven from political leadership, or—and perhaps more likely—that in most cases, coordination remains too technical to warrant political interest.

How well do DFIs and bilateral development agencies cooperate and what is the way forward?

This paper set out to investigate how DFIs and development agencies across DAC providers perceive their cooperation, the challenges they face, and how these could be overcome. The results from our survey highlight three take away messages that inform how cooperation is taking place and identifies actions for improvement.

- While cooperation between DFIs and development agencies exists, its scope is primarily limited to knowledge sharing. Experience and knowledge sharing between institutions can help drive change and contribute to strengthening institutions’ financial capacities and expertise. While this type of cooperation is important, particularly as development agencies note that shortage of in-house expertise appears to be one of the main obstacles to scaling-up blended finance operations,[30] action-oriented forms of collaboration - such as de-risking, pipeline development, and co-designing strategies are crucial to mobilising additional investments. Nevertheless, these are all mentioned as current forms of cooperation by less than 50 percent of respondents. To address this gap, DFIs and development agencies need to focus on strengthening cooperation beyond knowledge exchange by implementing action-oriented strategies tailored to their expertise. This may require innovative financial tools and instruments (one example is the FISEA+ facility managed by Proparco, supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which aims to promote growth and jobs in Africa).[31]

- DFIs and development agencies hold divergent perspectives on the success of their current cooperation efforts, which likely reflects differences in their cooperation goals and motivations. Our survey showed that DFI respondents express higher satisfaction with current levels of cooperation than development agencies, which reported more challenges and perceive less effective cooperation with DFI counterparts. This discrepancy could be attributed to the institutions’ asymmetry in organisational objectives and incentives, which were highlighted by survey respondents as a key challenge to cooperation (Figure 5). Linked to the understanding that DFIs tend to follow a market-led approach, responding to private sector needs through case-by-case transactions, while development agencies are more policy driven and concerned with longer-term and systemic development impact, divergent objectives likely impact the degree to which cooperation can support such goals. For instance, while DFIs may view cooperation through a lens of achieving financial returns, development agencies may prioritise development impact. While differences in the objectives, mandates and approaches of both institutions is at the crux of the complementarity between development agencies and DFIs, there is a need to articulate a shared theory of change for how cooperation can improve results and help both agencies to deliver on their core objectives.

- Staff from DFIs and development agencies are willing to enhance cooperation. Our findings reveal that despite holding different perceptions of the success of current cooperation efforts, respondents from both institutions see value in investing time and resources to enhance cooperation. This presents a valuable opportunity for stakeholders to reform existing systems and foster institutional collaboration. Rather than aiming for ambitious goals in the beginning, donors should focus on identifying simple and achievable cooperation opportunities.[32] Our survey responses emphasise two areas where stakeholders appear particularly interested in fostering collaboration. First, to strengthen strategic planning, it was suggested that agencies should work to improve “line-of-sight” into project pipelines, to identify opportunities for coordinated action earlier in the project process. Second, at the country and project level, DFIs and development agencies could work together to generate investment opportunities, structuring blended finance operations that benefit from DFI financial expertise and development agency know-how, and taking part in joint impact reports and evaluations.

Conclusions

In the years ahead, the reality of increasingly stretched public budgets will continue to put pressure on development resources and will require governments to re-think how parts of their development system can work together more effectively to enhance development action. For DFIs and development agencies which utilise complementary approaches that can buttress each other’s actions, there is room and willingness to explore ways to improve cooperation and make better use of the resources, knowledge, and tools available across government to enhance each providers’ impact and contribution to development.

References

BII. “Nepal Invests is launched by CDC, FMO and SDC to accelerate investment in Nepal.” 19 March 2021. Accessed September 2023. https://www.bii.co.uk/en/news-insight/news/nepal-invests-is-launched-by-cdc-fmo-and-sdc-to-accelerate-investment-in-nepal/

Bilal, San, and Karim Kiraki. Enhancing coordination between European donors, development agencies and DFIs/PDBs: Insights and recommendations. Brussels : ETTG, 2022. https://ettg.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Enhancing-coordination-between-European-donors-ETTG-brief-september-2022.pdf

Bilal, San, Manuel Bueno, Faty Dembele, Manuela S. Fulga, Nancy Lee, Lasse Moller, Valeria Ramundo Orlando, Esme Stout, and Alvino Wildschutt-Prins. “The Role of DFIs and Their Shareholders in Building Back Better in the Wake of Covid-19.” Tri Hita Karana Working Paper for Development Finance Institutions. October 2020. https://assets.ctfassets.net/4cgqlwde6qy0/2UIDzHLqOh58RKeuHqejft/6a934d233516039a7c239014ce466b6d/THK_Report_on_Covid-19_and_Blended_Finance_21-10-2020.pdf

Lee, Nancy, and Dan Preston. The Stretch Fund: Bridging the Gap in the Development Finance Architecture. CGD Brief, 2019. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/Lee-Preston-Stretch-Fund-Full.pdf

Lee, Nancy, Mauricio Cardenas Gonzalez and Samuel Pleeck. “More Blended Finance? Not So Much: The Results of CGD’s Survey on Aid Agencies and Blended Finance.” Center for Global Development (Blog), March 18, 2022. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/more-blended-finance-not-so-much-results-cgds-survey-aid-agencies-and-blended-finance

Lemma, Alberto, Dirk Willem te Velde, Judith Tyson and Samantha Attridge. “Four Views on How Development Finance Institutions Must Invest Better.” ODI, April 8, 2021. https://odi.org/en/insights/four-views-on-how-development-finance-institutions-must-invest-better/

OECD. “Development Finance Institutions and Private Sector Development.” Accessed November 27, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/development/development-finance-institutions-private-sector-development.htm

Van Rhyn, Justin, Irene Hu, and Matt Ripley. Bridging The Gap: Unlocking Synergies between Private Sector Development and Development Finance. London: British International Investment, 2022.https://assets.bii.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/21173508/Unlocking-synergies-between-private-sector-development-and-development-finance-institutions.pdf

Notes

[1] We understand DFIs as specialised development bank or subsidiaries set up to support private sector development in developing countries, based on the OECD’s definition. “Development finance institutions and private sector development,” OECD, accessed November 27, 2023, https://www.oecd.org/development/development-finance-institutions-private-sector-development.htm

[2] San Bilal and Karim Kiraki, Enhancing coordination between European donors, development agencies and DFIs/PDBs: Insights and recommendations (Brussels: ETTG, 2022), https://ettg.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Enhancing-coordination-between-European-donors-ETTG-brief-september-2022.pdf; Justin van Rhyn, Irene Hu and Matt Ripley, Bridging The Gap: Unlocking Synergies between Private Sector Development and Development Finance (London: British International Investment, 2022). https://assets.bii.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/21173508/Unlocking-synergies-between-private-sector-development-and-development-finance-institutions.pdf

[3] Van Rhyn et al., Bridging The Gap.

[4] For example, through the Association of European Development Finance Institutions (EDFI) and the Practioners’ network for development.

[5] Bilal and Kiraki, Enhancing coordination between European donors, development agencies and DFIs/PDBs.

[6] Our sample included Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States.

[7] We understand “development agencies” as the primary actor responsible for managing bilateral development cooperation within a government system. This includes ministries of foreign affairs or separate implementing agencies. Where two actors share primarily responsibility for development policy and implementation, we contacted both (for example, for Germany, our survey was shared with both BMZ and GIZ).

[8] While the authors understand that that EDCF (part of EXIM Bank) is not strictly considered a DFI, the fund is included in this research as it provides similar financial tools such as development project loans.

[9] This includes 10 occurrences for which we collected answers from both the DFI and development agency of a same provider.

[10] Van Rhyn et al., Bridging The Gap.

[11] Bilateral development agency responses 1,2,6,8,9,10,11,12 and 14; DFI responses 4,5,7 and 10.

[12] Bilal and Kiraki, Enhancing coordination between European donors, development agencies and DFIs/PDBs.

[13] Nancy Lee, Mauricio Cardenas Gonzalez and Samuel Pleeck, “More Blended Finance? Not So Much: The Results of CGD’s Survey on Aid Agencies and Blended Finance,” Center for Global Development (Blog), March 18, 2022, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/more-blended-finance-not-so-much-results-cgds-survey-aid-agencies-and-blended-finance

[14] Bilal and Kiraki, Enhancing coordination between European donors, development agencies and DFIs/PDBs.

[15] DFI responses 4, 6, 8, 9

[16] DFI response 4

[17] Bilateral development agency responses 1, 3, 5.

[18] Bilateral development agency responses 1, 9,

[19] Bilateral development agency responses 1, 3, 10, 11.

[20] Nancy Lee and Dan Preston, The Stretch Fund: Bridging the Gap in the Development Finance Architecture, CGD Brief (2019), https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/Lee-Preston-Stretch-Fund-Full.pdf

[21] Van Rhyn et al., Bridging The Gap, 8.

[22] Alberto Lemma, Dirk Willem te Velde, Judith Tyson and Samantha Attridge, “Four views on how development finance institutions must invest better,” ODI, April 8, 2021, https://odi.org/en/insights/four-views-on-how-development-finance-institutions-must-invest-better/

[23] San Bilal, Manuela Bueno, Faty Dembele, Manuela S. Fulga, Nancy Lee, Lasse Moller, Valeria Ramundo Orlando, Esme Stout, and Alvino Wildschutt-Prins, “The Role of DFIs and their shareholders in building back better in the wake of Covid-19,” Tri Hita Karana Working Paper for Development Finance Institutions (October, 2020). https://assets.ctfassets.net/4cgqlwde6qy0/2UIDzHLqOh58RKeuHqejft/6a934d233516039a7c239014ce466b6d/THK_Report_on_Covid-19_and_Blended_Finance_21-10-2020.pdf

[24] DFI responses 4,7,8 and 10. Towards this end, respondent 8 suggested “staff exchange and secondment between DFI and agencies” as a solution to increase cross-institutional knowledge and expertise Bilateral development agency responses 1,7,10,12,13 and 14.

[25] Bilateral development agency responses 7 and 12.

[26] DFI responses 3,5 and 10. Bilateral development agency responses 3,5,6,10 and 13.

[27] DFI response 5

[28] DFI response 1; Bilateral development agency responses 1,2 and 9.

[29] BII, “Nepal Invests is Launched by CDC, FMO, and SDC to Accelerate Investment in Nepal,” March 19, 2021, accessed September 2023, https://www.bii.co.uk/en/news-insight/news/nepal-invests-is-launched-by-cdc-fmo-and-sdc-to-accelerate-investment-in-nepal/

[30] Nancy Lee et al., “More Blended Finance? Not So Much: The Results of CGD’s Survey on Aid Agencies and Blended Finance,” Center for Global Development (Blog), March 18, 2022, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/more-blended-finance-not-so-much-results-cgds-survey-aid-agencies-and-blended-finance

[31]San Bilal and Karim Kiraki, Enhancing coordination between European donors, development agencies and DFIs/PDBs.

[32]Ibid.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.