Recommended

Four takeaways

Introduction

About 20 to 40 percent of the US$7.1 trillion spent annually on healthcare worldwide is wasted, according to the World Health Organization. Today, politicians are under growing pressure to squeeze more out of every dollar and guarantee greater access to better, more affordable healthcare for their citizens. In such a resource-constrained environment, wasting trillions of dollars on health every year is not viable. However, the idea of withdrawing coverage is often politically unpopular. Even in the United States, where the Affordable Care Act is unpopular among the newly elected Republicans, pressures to sustain affordable health insurance remain.

The idea of better health for the money—whether it relates to buying expensive cancer drugs in the UK or to making the case for increasing donor funds to support less wealthy countries—is gaining wide consensus the world over. Good quality care for those who need it means (and requires) going beyond more money for healthcare. It also means demonstrating the ability of payers—public and private, global and national, federal and regional—to spend effectively to maximise the health return-on-investment (ROI) from the available resource envelope. And it also means attracting more public resources from other sectors, and, where possible, greater investments from the private sector. Indeed, making the case to national treasuries—or aid agencies in the case of the poorest countries—to increase spending on health is untenable without a strong justification for maximising the ROI of such investments.

This note provides an overview of some of the approaches and policy options that the National Health Service (NHS) in England has been using to maximise value for money—many of which provide useful examples to inform CGD’s recently launched Working Group on the Future of Global Health Procurement.

Four key lessons from NHS-England

Buying efficiently and demonstrating value for money with scarce healthcare monies is challenging for ministries of health around the world. While there has been progress, buying practices are still not as effective as they could be. The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which provides evidence-based guidance on improving the quality and availability of health care, is one example. NICE exemplifies a technocratic and procedurally fair attempt at resource allocation based on evidence of costs and benefits, by making tradeoffs between alternative investment choices explicit. By investing most of its own analytical capacity towards assessing new pharmaceutical products, NICE has proven to be a more effective tool for allocating additional funding when it becomes available than for identifying efficiencies and reducing waste within the NHS.

Indeed, current financial pressures in the UK have made it clear that NICE needs an intelligent and strong payer downstream to maximise value for money in the NHS. Recent policy actions include introducing budgetary ceilings for listings of orphan drugs; involving NHS England, the English healthcare payer established during the latest round of reforms, as a decision maker in the revamped Cancer Drugs Fund; and a decision to have NHS England negotiate prices for drugs already deemed cost-effective, but not necessarily affordable, by NICE. These examples all illustrate the need to more fully integrate smart buying into health decision-making, going beyond NICE-style cost-effectiveness analyses to include more realistic decision rules for maximising ROI in healthcare.

Below we list examples of how NHS England has been using tools such as price transparency, consolidated buying power, and value-based assessments to contain expenditure while still maintaining quality and access.

1. Leveraging collective buying power:

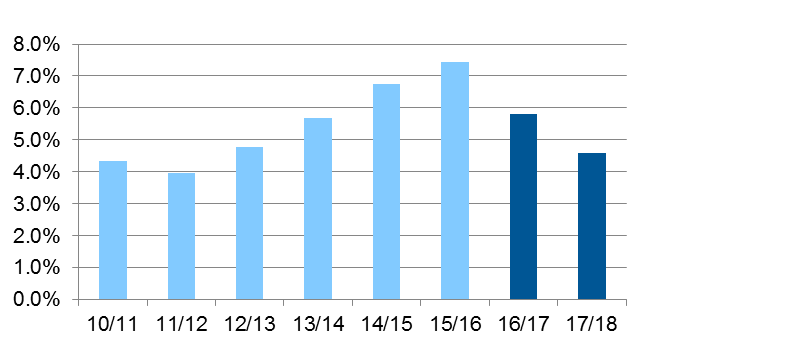

- In a seller’s market, this can be used to reduce competition, which drives up prices. The NHS has workforce shortages across several key professional groups, and by 2015-16 agency spending had risen to over 7 percent of the total pay bill. Part of the problem was individual hospital trusts, which operate quasi-independently, outbidding one another for a small pool of temporary staff. The regulator stepped in, setting hourly rate caps for key staff groups and requiring trusts to inform them of any occasions on which these were broken. This led to a marked reduction in “outbidding,” resulting in £1 billion in annual savings (figure 1).

- In a buyer’s market, this can be used to aggregate orders into larger contracts—encouraging maximum competition between suppliers, leading to lower prices. In the UK, the NHS Supply Chain makes collective purchases on behalf of the whole NHS. The Department of Health aims to save almost £600 million by 2021-22, partly by increasing the proportion of centrally procured items from 40 percent of spending on NHS equipment to 80 percent.

Figure 1: Agency spend as % of total pay bill

2. Improving the quality and transparency of information:

- The NHS has centrally funded a new tool called the Product Price Index Benchmark (PPIB), which hospital trusts in England submit data to on the prices they have paid for over 2 million different products.

- This has shown, for example, that some hospitals are paying over £16 for packs of rubber gloves being bought for as little as £0.35 by other trusts.

- More recently, the hospital regulator has also published a league table showing which trusts are paying the highest prices for common supplies.

- While the system remains relatively new, there are already examples of individual trusts reporting large savings. Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, for example, has reported 13 percent savings on everyday purchases.

- The process of submitting data, and then having it benchmarked against other purchasers, has also driven up the quality of management information—an essential step in any attempt to reduce purchasing costs.

3. Proactively shaping the drugs market:

- Drugs account for a large share of non-pay expenditure in all healthcare systems. The NHS spends some £15 billion on medicines each year.

- A key focus for all health systems is ensuring a healthy market exists for the manufacture of generic drugs, and that doctors and pharmacists are incentivised to prescribe and dispense these over branded drugs. The UK has the highest rates of generic drug use in Europe (figure 2), achieved through a highly competitive market and a centralized reimbursement system based on market prices submitted to the Department of Health (rather than, e.g., list prices). Legislation passed in 2017 also allows the government to step in and cap prices where there are large, unexplained price increases, an issue seen in many countries during recent years.

- For branded drugs, the UK runs the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS). This is a non-contractual agreement between the Department of Health and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), which sets an “allowed growth rate” for NHS expenditure on branded, licensed medicines—essentially capping the total costs to the NHS for this portion of total expenditures on drugs.

Figure 2: Share of generics in the total pharmaceutical market, 2014 (or nearest year)

4. Making evidence-based decisions about what to purchase, before getting into the how or from where:

- In the UK, NICE exists to make independent, evidence-based decisions about whether new technologies are sufficiently cost-effective to be funded by the NHS.

- In addition to its long-standing cost-effectiveness assessments, NICE has recently introduced a Budget Impact Test, assessing affordability to the NHS in addition to cost-effectiveness.

- The process involves a period of negotiation between the newly formed NHS England Commercial Development Unit and the company to try to reduce the budget impact of a new drug—and, if unsuccessful, a means of phasing the cost of its introduction.

Beyond NHS England

Indeed, there are rich experiences from around the world that reflect important lessons learned for maximising value for money in health:

- Performance-based pricing of goods and services through value-based insurance schemes (also known as “design for value”), as well as roll-out through integrated delivery platforms with the ability and willingness to share the investment risk, as in the case of accountable care organisations rather than individual physicians, are shaping the market for medicines innovation in an increasingly cost-conscious US environment.[1]

- Similarly, the UK government has become the first development assistance donor to introduce proof of value for money with an eye toward reducing inefficiency and waste as a conditionality of its own aid to the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

- The EU is pooling its purchasing power to get better prices for commodities through its first-ever joint procurement agreement, covering public health emergencies such as a continent-wide influenza outbreak. But, at the request of the French government, this will also cover the highly effective albeit expensive hepatitis C drugs. At the same time, southern European countries (plus Ireland) as well as the Low Countries are forming purchasing clubs to secure better prices.

- In New Zealand, the NICE-equivalent, PHARMAC, has for years combined Health Technology Assessment with well-known strategic purchasing tools for devices and pharmaceuticals, including price negotiations, competitive tendering with supply guarantees, budget caps and rebates, therapeutic reference pricing and prior authorisation requirements, none of which NICE is currently able to apply in the NHS.

- Thailand’s HITAP, NICE’s counterpart (but with broader powers to include direct price negotiation), has in a year secured over THB 1 billion in savings by negotiating down the list price of just three on-patent pharmaceutical products, including cancer and HIV drugs, approximately 0.2 percent of the country’s healthcare budget.

- And in Colombia, the government regulated the prices of patented medication between 2011 and 2014, benchmarking itself against high-income economies such as Canada and France which seemed to be getting a better deal. Having saved almost US$200 million, the scheme was abandoned. The country is now thinking of introducing value-based pricing after passing a law in 2015—but the pressures against such a move from multinational industry and OECD country governments remain high. In the meantime, latest market data suggest a shift towards higher volumes of unregulated drugs slowly making up for the savings secured so far.

- The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is committing resources to strengthen purchasing and resource allocation choices, including the multi-million dollar International Decision Support Initiative (iDSI) for improving investment decisions, which was scoped out CGD’s Priority-Setting Institutions Working Group.

Whether through strategic purchasing, evidence-informed commissioning, or value-based insurance, the quest for squeezing better value out of existing resources is truly a global priority. But lack of clarity regarding healthcare investment goals coupled with low technical capacity in ministries of health or national health insurance funds, together with multiple competing interests for attracting healthcare dollars make proactive evidence-informed purchasing hard to achieve. The reluctance of India’s central government to increase the healthcare budget despite the dire need, as well as the delays in committing the required resources for rolling out South Africa’s ambitious National Health Insurance Scheme perhaps reflect concerns amongst national treasuries of their respective healthcare sectors’ ability to spend wisely.

Conclusion

What do we need to fill the payer skills gap? Better, more publicly (and more widely) available information on costs and prices of goods and services; vigorous homegrown technical expertise for applying this information to making better investment decisions; and, perhaps most crucially, stronger independent and accountable global and national institutions for monitoring the implementation of the decisions, measuring their impact, and then course-correcting as required. And perhaps, more collaborative thinking and doing, globally: can we pool our resources to buy better together?

Ed Rose is Senior Adviser to the Chief Executive of NHS England, and a member of CGD’s Working Group on the Future of Global Health Procurement.

[1] JC Robinson Biomedical Innovation in The Era Of Health Care Spending Constraints

DOI 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0975 HEALTH AFFAIRS 34, No 2 (2015): 203–209

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.

More Reading