Role

Since 1971, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) has served as the US government’s development finance institution. OPIC works to mobilize private capital to address development challenges while advancing US foreign policy priorities—furthering strategic, development, economic, and political objectives. OPIC aims to catalyze investment abroad through loans, guarantees, and insurance, which enable OPIC to complement rather than compete with the private sector. The independent agency also plays a key role in helping US investors gain a foothold in emerging markets and is barred from supporting projects that could have a negative impact on the US economy.

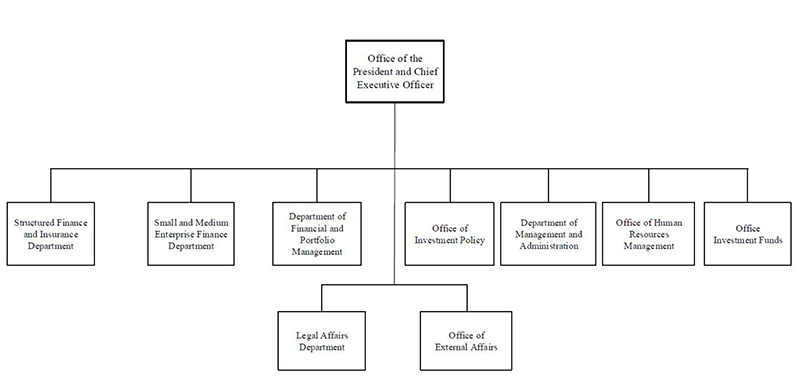

Structure and Leadership

A 1969 amendment to the US Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195) provides the basis for OPIC’s governance structure, vesting the agency’s powers in a board of directors.[1] The board provides policy guidance to OPIC, and projects considered major or risky must secure its approval.[2] All members of the agency’s board of directors, including the president and CEO of the OPIC, are appointed by the president of the United States and confirmed by the US Senate. The board is composed of seven members from the government and eight from the private sector.

- Government members. Three seats on OPIC’s board are designated for specific officials: OPIC’s president/CEO, the administrator of USAID, and the US trade representative or deputy US trade representative. The remaining four seats must be filled by senior government officials, including a representative from the Department of Labor.

- Private sector members. Private sector members are appointed to three-year terms. The eight private sector seats include four seats for members with experience reflecting OPIC’s core competencies—two with experience in small business, one with experience in cooperatives, and one with experience in organized labor.

The US president is also charged with nominating an executive vice president for the agency, a role subject to Senate confirmation.[3] OPIC has 10 offices organized under the Office of the President/CEO.

Budget

OPIC is entirely self-sustaining; in fact, it has returned a net profit to the US Treasury for 40 consecutive years. In other words, OPIC’s revenue from investments (consisting of interest on loans and fees from loan guarantees and insurance) consistently exceeds congressionally appropriated administrative expenses. In FY2015, OPIC collected $321 million in revenue while administrative expenses totaled only $87.8 million, including $400,000 for inspections and evaluations.[5] In sum, OPIC returned a net profit of $233.2 million to the US government. By law, OPIC is limited in the amount of risk it can take on—capping the agency’s total portfolio at $29 billion.[6]

|

Year |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 (Enact) |

FY17 (Request) |

|

Appropriations |

8 |

70 |

80 |

77 |

90 |

88 |

83 |

108 |

|

Net Collections |

288 |

263 |

346 |

408 |

300 |

321 |

366 |

449 |

OPIC’s Model

OPIC can catalyze transactions in developing countries that private investors are unable or unwilling to pursue without the agency’s involvement. As a publicly backed institution, OPIC is able to play a unique role to overcome market failures. The agency’s commitments are backed by investment agreements with developing country governments and by the political and economic force of the US government. In addition, OPIC is mission driven to advance development and US foreign policy priorities and coordinates activities with other US government agencies. These features help OPIC bring value to transactions that private investors cannot.[13] Examples of the ways in which OPIC uses its unique position include engaging in countries considered high risk by private investors, providing loan terms that commercial financiers and insurers are unwilling to offer (such as longer-term loans), and supporting projects that demonstrate innovations or new technologies.[14]

To qualify for OPIC support, projects must fulfill a number of eligibility requirements, including proving OPIC support is necessary for the project to go forward and meeting environmental, social, and corporate governance standards. Projects require a substantial US connection—the project must be sponsored by a US-organized entity, a majority-US owned foreign-organized entity, or a US citizen.[15] Projects also are restricted to one of 160 developing or post-conflict countries.

Instruments

OPIC provides financing, political risk insurance, and support for private equity funds.

- Financing. OPIC offers two types of financing—direct loans and loan guarantees—to projects that are commercially and financially sound.[16]

- Direct loans. OPIC helps finance eligible projects in developing countries by issuing direct loans. To issue these loans, OPIC borrows from the US Treasury. OPIC collects the loan repayment with interest from the borrower to repay Treasury. OPIC may also use authority from Congress to self-fund subsidies that allow the agency to offer long-term loans. Loan size typically ranges from $350,000 to $250 million, although OPIC has approved loans for up to $400 million.[17] OPIC’s involvement is typically limited to 75 percent of the total project cost, although it is often far less.[18]

- Loan guarantees. OPIC can also offer loan guarantees to support eligible projects. To provide loan guarantees, OPIC acts as the initial project lender and then issues shares of project debt to third-party investors. The agency agrees to repay the loan to investors in the event of a default by the borrower.[19] Consistent with commercial lending practices, OPIC collects guarantee fees for this service. OPIC does not guarantee more than 75 percent of a total project cost, with only limited exceptions.[20]

- Insurance. OPIC offers political risk insurance primarily to protect against three types of risk: political violence, currency inconvertibility, and expropriation. Currency inconvertibility insurance guards against the inability to convert funds from local currency to US dollars, while expropriation insurance protects projects against the nationalization, confiscation, or other forms of expropriation by a host government.[21] Insurance fees are calculated based on the project and the investor. OPIC cannot insure more than 90 percent of a project by law.[22]

- Support for private equity funds. OPIC sponsors the creation of privately owned and managed investment funds.[23] These private equity funds help increase private capital flows in developing countries and can make direct equity and equity-related investments in new or expanding companies in emerging markets. OPIC provides loan guarantees to the fund managers, who are typically US investment professionals selected by OPIC. In turn, the funds invest in local companies, often helping to finance small and medium enterprises through loans, equity investments, and technical advice.[24]

Activities

Financing Infrastructure Needs: OPIC’s portfolio is heavily oriented toward financing infrastructure projects, such as electricity generation and transportation needs. In 2016 alone, OPIC committed $1.4 billion to energy and other infrastructure projects, and 34 percent of OPIC’s current portfolio consists of energy, transportation, or warehousing projects.[25] Electricity is a major constraint to growth for one in three firms in the developing world, according to World Bank surveys.[26] Under the George W. Bush administration, OPIC’s infrastructure portfolio focused more heavily on extractive sector projects, like oil and gas exploration and industrial mining. Under the Barack Obama administration, OPIC provided considerable support for electricity infrastructure investments through Power Africa, President Obama’s signature electrification initiative.[27] OPIC had been constrained in supporting a full range of investments in the energy sector by a cap on the total greenhouse gas emissions of projects in its portfolio. Since FY2014, Congress has effectively lifted the cap in annual appropriations measures, granting OPIC greater opportunity to explore support for fossil fuel projects overseas.[28]

Extending Financial Credit: Financial services projects make up almost half of OPIC’s current portfolio—45 percent. For instance, OPIC may extend financial credit to microfinance institutions and small and medium enterprises in developing countries, addressing a critical need. Access to finance is a common obstacle to firm growth in developing countries.[29]

Working in Higher-risk Countries: As part of its mandate to address development challenges, OPIC works in lower-income and higher-risk countries that may face considerable development challenges and suffer less developed capital markets. In 2016, all of OPIC’s commitments went to low- and middle-income countries.[30] Despite what appears to be a greater appetite for risk than private creditors, OPIC writes off very few of its direct loans—only 1 percent of total outstanding direct loans on average each year between 2001 and 2013.[31]

Supporting American Small businesses: OPIC is statutorily required to give preferential consideration to projects that involve US small businesses, ensuring a significant portion of OPIC’s portfolio supports small businesses.[32] OPIC can help small businesses overcome obstacles, such as political risk and lack of capital, when expanding overseas.[33] The agency offers political risk insurance to small businesses at a reduced cost and with a streamlined approval process.[34] Much of OPIC’s portfolio includes projects sponsored by small businesses—only a modest percentage of OPIC’s commitments support projects sponsored by Fortune 500 corporations.[35]

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Congress, “Foreign Assistance Act of 1969, Title IV,” Pub. L. No. 91–275, § 231-251 (1969), https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/statute1.pdf.

[2] Office of Inspector General, USAID, “Assessment of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation’s Development Outcome and Compliance Risks.” (Office of Inspector General, USAID, May 15, 2015), https://oig.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/audit-reports/8-opc-15-002-s.pdf.

[3] Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, “United States Government Policy and Support Positions” (US Government Publish Office, December 1, 2016), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016/pdf/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016.pdf.

[4] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “Annual Management Report of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation for the Fiscal Years 2016 and 2015” (Overseas Private Investment Corporation, November 15, 2016), https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/files/2016_Annual_Management_Report.pdf.

[5] The USAID inspector general is empowered to perform inspections and investigations of OPIC as necessary. In recent years, a memorandum of understanding has ensured the inspector general is reimbursed by OPIC for the costs of any auditing and review. Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “Congressional Budget Justification, Fiscal Year 2017” (Overseas Private Investment Corporation, 2016), https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/files/OPIC%20FY2017%20%20Congressional%20Budget%20Justification%20-%20FINAL.pdf.

[6] There are additional maximum exposure limits for regions and instruments, as well as limits on the amount of the portfolio that is liable to a single investor. Specific numbers can be found in OPIC’s statute and annual reports: U.S. Congress, Foreign Assistance Act of 1969, Title IV.

[7] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “Congressional Budget Justifications, Fiscal Years 2012-2017.” (Overseas Private Investment Corporation, 2016), https://www.opic.gov/media-events/annual-reports.

[8] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “OPIC Portfolio Data as of 9/30/2016.” (Overseas Private Investment Corporation, September 30, 2016), https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/OPIC_Portfolio_Data_as_of_9_30_2016.xlsx. Unless noted, all numbers are for the OPIC portfolio as of 9/30/2016.

[9] Excluding regional projects.

[10] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “Congressional Budget Justification, Fiscal Year 2017.”

[11] Giulia Christianson, Shally Venugopal, and Shilpa Patel, “Unlocking Private Climate Investment: Focus on OPIC and Ex-Im Bank’s Use of Financial Instruments,” Working Paper, Public Financial Instruments (World Resources Institute, September 2013), http://pdf.wri.org/unlocking_private_climate_investment_focus_on_opic_and_exim.pdf.

[12] Shayerah Ilias Akhtar, “The Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Background and Legislative Issues,” CRS Report (Congressional Research Service, December 22, 2016), https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20161222_98-567_1d50a9d6a907d7cb9ea2f9f36533559e2a102721.pdf; Daniel F. Runde and Conor M. Savoy, “Sharing Risk in a World of Dangers and Opportunities: Strengthening U.S. Development Finance Capabilities.” (Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 7, 2011), https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/111205__Runde_SharingRisk_Web.pdf.

[13] Theodore H. Moran and C. Fred Bergsten, “Reforming OPIC for the 21st Century,” International Economics Policy Briefs (Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 2003), https://piie.com/sites/default/files/publications/pb/pb03-5.pdf; Benjamin Leo and Todd Moss, “Bringing US Development Finance into the 21st Century: Proposal for a Self-Sustaining, Full-Service USDFC,” Rethinking US Development Policy (Center for Global Development, March 17, 2015), /publication/bringing-us-development-finance-21st-century-proposal-self-sustaining-full-service-usdfc.

[14] Government Accountability Office, “Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Additional Actions Could Improve Monitoring Processes,” Report to Congressional Requestors (Government Accountability Office, December 2015), http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/674142.pdf.

[15] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “OPIC Fact Sheet: U.S. Connection Requirements for OPIC-Supported Projects.” (Overseas Private Investment Corporation, January 2016), https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/files/us-nexus-fact-sheet-2016.pdf.

[16] Akhtar, “The Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Background and Legislative Issues.”

[17] Ibid.; Benjamin Leo and Todd Moss, “Inside the Portfolio of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation,” Policy Paper (Center for Global Development, April 2016), /sites/default/files/CGD-Policy-Paper-81-Leo-Moss-Inside-the-OPIC-Portfolio.pdf.

[18] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “Eligibility,” Overseas Private Investment Corporation, 2017, https://www.opic.gov/what-we-offer/financial-products/eligibility.

[19] Christianson, Venugopal, and Patel, “Unlocking Private Climate Investment: Focus on OPIC and Ex-Im Bank’s Use of Financial Instruments.”; Office of Inspector General, USAID, “Assessment of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation’s Development Outcome and Compliance Risks.”

[20] U.S. Congress, Foreign Assistance Act of 1969, Title IV.

[21] Akhtar, “The Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Background and Legislative Issues.”

[22] U.S. Congress, Foreign Assistance Act of 1969, Title IV.

[23] Under current law, OPIC lacks the authority to make equity investments outside of private investment funds.

[24] Carol Lancaster et al., Foreign Aid and Private Sector Development (Watson Institute for International Studies, Brown University, 2006), http://www.watsoninstitute.org/pub/ForeignAid.pdf.

[25] Benjamin Leo, “The OPIC Scraped Portfolio Dataset.” (Center for Global Development, April 21, 2016), /media/opic-scraped-portfolio-dataset.

[26] Benjamin Leo, “Is OPIC Focused on the Private Sector’s Biggest Constraints?,” Center For Global Development, US Development Policy, (May 12, 2016), /blog/opic-focused-private-sectors-biggest-constraints.

[27] Leo and Moss, “Inside the Portfolio of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation.” Between 2013 and 2016, OPIC provided over 2 billion in commitments to power projects, including renewable projects, in sub-Saharan Africa.

[28] Todd Moss, Roger Jr. Pielke, and Morgan Bazilian, “Balancing Energy Access and Environmental Goals in Development Finance: The Case of the OPIC Carbon Cap,” Policy Paper (Center for Global Development, April 2014), /sites/default/files/balancing-energy-access-case-opic-carbon-cap_0.pdf.

[29] Leo, “Is OPIC Focused on the Private Sector’s Biggest Constraints?”

[30] Leo, “The OPIC Scraped Portfolio Dataset.”

[31] Leo and Moss, “Inside the Portfolio of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation.”

[32] Akhtar, “The Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Background and Legislative Issues.”

[33] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “Outreach Events for American Small Businesses,” Overseas Private Investment Corporation, 2016, https://www.opic.gov/outreach-events/overview.

[34] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “OPIC Handbook” (Overseas Private Investment Corporation, 2007), https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/docs/OPIC_Handbook.pdf.

[35] Benjamin Leo, “Is OPIC Corporate Welfare? The Data Says...,” Center For Global Development, US Development Policy, (April 19, 2016), /blog/opic-corporate-welfare-data-says.

[36] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “OPIC Portfolio Data as of 9/30/2016.”

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.