Recommended

Event

VIRTUAL

November 16, 2022 2:00—3:00 PM Eastern Time (US & Canada)/ 7:00—8:00pm Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)Latin American Committee on Macroeconomic and Financial Issues Statement No. 45

1. Causes of inflation in Latin America

Inflation has become a central feature of the global economy. In Latin America (aside from idiosyncratic cases such as Argentina and Venezuela, where high inflation rates have long been the norm), inflation began to rise the first half of 2021, at the same time it did in the US. The fact that rising inflation has been a synchronized global phenomenon reflects two main causes, both directly related to the Covid-19 pandemic and the associated policy response.

Lockdowns and mobility constraints around the world generated an adverse supply shock, involving serious disruptions in global supply chains and the virtual shutdown of important economic sectors. At the same time, and most importantly in the view of the Committee, the fiscal and monetary policy responses in the US and other economies generated an unprecedented increase in aggregate demand. The expansion of monetary aggregates triggered by the Federal Reserve in the early months of the pandemic dwarfed the monetary expansions that occurred during previous crisis episodes, including the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

Initially, and similarly to what happened in 2008-09, the monetary expansion was not associated with inflationary pressures. Back then, the Fed expanded its balance sheet to compensate for the destruction of private liquidity that occurred after the fall of Lehman. In 2020, by contrast, there was a sharp increase in the precautionary demand for money. So, despite the 20-percentage point increase in the ratio of M2 to GDP, there was no obvious disequilibrium between the demand for and the supply of liquidity. Thus, in the early months of the pandemic, inflationary pressures did not materialize.

But when the pandemic started to recede, the situation changed drastically. The precautionary motive that had induced the sharp increase in the demand for money gradually started to reverse, creating incipient excess liquidity in the US. In addition, the US embarked on large and reiterated fiscal expansions. The net effect was that inflationary pressures surfaced around May 2021, accelerated in early 2022, and in June peaked at nearly 9% over 12 months, the highest such figure in over four decades.

Initially, it was unclear to what extent inflation was driven by the adverse supply shocks or by the sharp increase in aggregate demand associated to the expansionary monetary and fiscal stance. Many observers tended to stress the global supply chains disruptions as the main driver of inflation, concluding that the phenomenon would likely be transitory and therefore did not require an immediate tightening of monetary policy. Moreover, after over a decade of very low inflation and even deflationary pressures, the Federal Reserve had become strongly concerned about the potential impact of policy normalization on the labor market and economic activity. The result was that monetary policy in the US and other advanced economies fell behind the curve, and the response to rapidly rising inflation was delayed, while supply constraints remained.

These developments had a negative impact on Latin America. Given the dominant role of the US dollar in the invoicing of global trade, rising US inflation translated in higher imported inflation. Moreover, international capital markets became increasingly worried about the eventual need for a sharp tightening in US monetary policy, which caused currency depreciations across the region. Weaker currencies, in turn, added to domestic inflationary pressures.

In addition to the effects of policies in the US and other advanced economies, local—and synchronized--policy actions also played a role on the path of inflation. As in most other regions, Latin American governments conducted expansionary fiscal policies to support firms and households during the pandemic, albeit with significant differentiation among countries. These expansions were not quickly reversed as consumption recovered, adding, therefore, to pressures on currency depreciations and inflation.

2. Policy response

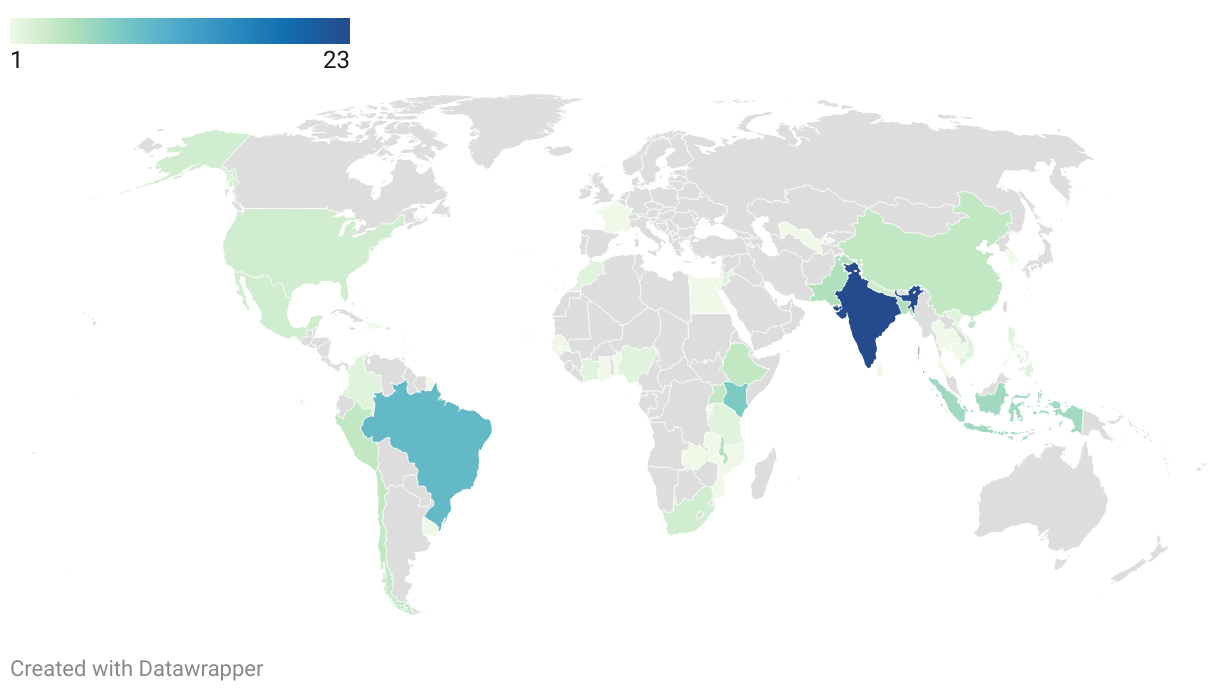

Unlike the Federal Reserve, which was late to react to inflation and initiated its tightening cycle in March 2022, the policy response of Latin American central banks was timely. Brazil’s Central Bank was the first to launch a preemptive tightening cycle in May 2021, followed by Mexico in June 2021, Chile in July 2021 and Peru in August 2021. The rapid reaction of central banks to increasing inflation had several sources. The combination of higher imported inflation and depreciating currencies prompted central banks in the region to act early and preemptively to avoid a repeat of costly past inflationary experiences. The policy tightening was also seen as an indispensable response to tightening global liquidity conditions and the resulting pressures in foreign exchange markets. Avoiding excessive depreciations can be desirable in countries with financial fragilities, in order to prevent harmful balance sheet effects and the potential shift to an inferior equilibrium.

3. Prospects of inflation in the region and risks

US inflation appears to have peaked, but significant uncertainty still exists about its persistence and the potential impact of monetary tightening on economic activity. The Federal Reserve projects to bring its monetary policy rate in the range of 4.5% to 5% in 2023. It is encouraging that inflation expectations remain well anchored, reflecting the significant credibility acquired by the Fed in recent decades, although backward-looking expectations cannot be discounted.

The Committee believes other factors may contribute to a faster-than-anticipated reduction of global inflation. First, monetary tightening is currently occurring simultaneously across regions. Second, increased risk indicators and lower prices for US Treasuries along the entire yield curve cut back on global liquidity and reduce available collateral in international capital markets. Third, quantitative tightening both in the US and Europe have complemented the increase in monetary policy rates.

In Latin America, the early tightening by central banks appears to be achieving the desired results. Inflation in Brazil has come down sharply in the last couple of months, and Brazil appears to be controlling inflation without inducing a recession so far. Moreover, in the context of elevated fiscal imbalances, the recent monetary response demonstrates the independence of many Latin American central banks from fiscal pressures.

In short, assuming a base-case scenario where no sudden stops take place, the Committee believes that inflation in the region may start to fall more rapidly over the coming months. With luck, a hard landing scenario can be avoided. Unfortunately, countries such as Argentina and Venezuela are likely to continue to experience high inflation, reflecting idiosyncratic factors and endemic macro-policy weaknesses.

4. Policy implications

The global scenario remains highly uncertain. While inflation is starting to decline, it is still too early to declare victory.

Moreover, higher global interest rates increase the risk that the record-high debt levels reached during the Covid pandemic may become unsustainable. This is reflected in emerging markets high yield spreads, which remain at extremely elevated levels, only comparable to the peaks reached under the Covid pandemic and the Lehman collapse. At the same time, spreads on investment-grade emerging market assets have increased but less sharply.

In this context, the Committee believes that central banks in Latin America need to be cautious and maintain their current tight stance until there is clear evidence that inflation is receding. A premature loosening of monetary policy may hamper hard-earned credibility.

In the current context of significant capital outflows from emerging markets, authorities also need to prepare for the possibility of disruptive sudden stops in international capital markets. In this context, the Committee believes that the burden of the policy preparedness cannot fall exclusively on central banks. Fiscal policy needs to play a major complementary role, since it is debt markets that may be subject to sudden volatility. Smaller structural budget deficits and larger liquidity buffers will be critical in reducing financial vulnerability.

Moreover, it is worth keeping in mind that excess optimism could carry serious risks. The pace of monetary tightening in the US and the flight towards the USD have accelerated since the onset of the pandemic and are likely to increase global macro and financial volatility. This is already partly reflected in the large, unexpected appreciation of the USD. It faces policymakers with challenges that have no clear historical precedent—e.g., the extremely large monetary aggregates’ volatility of reserve currencies since WWII—and policy proposals will unlikely meet with wide agreement across government’s branches. The Committee believes that coordination across government (e.g. the finance ministry, the central bank, state owned banks and when, applicable, the banking system regulator), well before it is needed, is highly desirable, but confidentiality is essential. Without it, the mere discussion of crisis scenarios may be self-fulling and, of course, counterproductive.

As is by now widely appreciated, the policy response to the Covid pandemic resulted in record levels of public debt both in developed economies and in emerging and developing countries. Although liquidity levels —in particular, international reserves— are higher than in previous episodes of capital market volatility, high indebtedness poses a significant risk specially to emerging markets, as suggested by strong and ongoing outflows from these markets during 2022.

High risk levels can be particularly harmful if a credit event in one emerging market generates contagion to other economies and becomes systemic. In such circumstances, otherwise fundamentally sound economies may end up in a bad equilibrium. So far, contagion has not happened —for instance, in the case of Sri Lanka— because fundamentals in countries forced to enter a restructuring were particularly out of line and not indicative of the same situation happening elsewhere. But, as mentioned above, current market conditions and risk indictors among high/yield emerging market and developing economies are only comparable to those prevailing at the start of the Covid pandemic or at the time of the collapse of Lehman in 2008. This is a clear indication of potential vulnerability.

Financial contagion can involve an externality that requires a systemic response. The Committee believes that the international official community should consider promoting specific actions directed at reducing debt levels in emerging and developing countries, for instance, through debt buybacks. In particular, the Committee believes that, as part of its programs and especially those requiring exceptional access, the IMF should set aside a portion of its assistance to finance exclusively debt buybacks.

There are two important reasons why debt buybacks are efficient, on top of reducing the above/mentioned externality. Firstly, IMF programs often rely on the expectation that its catalytic role will allow countries to re access the capital market and obtain the financing necessary to repay the Fund. As shown by the Argentine program, this expectation may turn out to be overly optimistic because governments do not necessarily take the necessary actions to restore debt sustainability and have an incentive to use Fund resources in the short-term disregarding the debt burden that is passed over to future administrations. In this context, debt buybacks circumvent political myopia and address debt sustainability directly. Secondly, in the absence of an efficient mechanism for orderly debt restructuring of sovereign debt, IMF-driven debt buybacks may be an efficient tool to de facto restructure debt and avoid costly defaults and debt restructuring processes.

Finally, the Committee believes that, now more than ever, it is essential that economic policy be supported by political authorities. Many countries in the region are experiencing more polarized political environments and new governments are facing unusual economic challenges. Policymakers should stay the course and strive to consolidate political support from the widest possible spectrum of sectors. The ability to muster political support and stability have become essential components of investors’ confidence and, hence, of financial sustainability.

The Latin American Committee on Macroeconomic and Financial Issues (CLAAF, for its acronym in Spanish) gratefully acknowledges financial support by the Center for Global Development, the Central Bank of Chile, and FLAR for funding its activities during 2022. The Committee thanks Nayke Montgomery Guzmán for his support in the production of this statement. The Committee is fully independent and autonomous in drafting its statements.

This statement was jointly produced by:

Laura Alfaro, Warren Albert Professor, Harvard Business School, Former Minister of National Planning and Economic Policy, Costa Rica

Guillermo Calvo, Professor, University of Columbia; former Chief Economist, Inter-American Development Bank

José De Gregorio, Professor of Economics, University of Chile. Former Governor of the Central Bank and former Minister of Economy, Mining, and Energy, Chile

Pablo Guidotti, Professor of the Government School, University of Torcuato di Tella; former Vice minister of Economy, Argentina

Ernesto Talvi, Senior Fellow, Real Instituto Elcano, Madrid, former Executive Director of CERES and former Minister of Foreign Relations, Uruguay

Liliana Rojas-Suarez, president, CLAAF; Senior Fellow and Director of the Latin American Initiative, Center for Global Development; former Chief Economist for Latin America, Deutsche Bank

Andrés Velasco, Dean of the School of Public Policy, London School of Economics, UK. Former Finance Minister of Chile

Nayke Montgomery was responsible for the Spanish translation of the statement, and supported the CLAAF meetings.

Comité Latino Americano de Asuntos Financieros, Declaración No. 45

1. Causas de la inflación en América Latina

La inflación se ha convertido en un factor central de la economía mundial. En América Latina (con la excepción de casos idiosincrásicos como Argentina y Venezuela, donde las altas tasas de inflación han sido la norma durante mucho tiempo), la inflación comenzó a aumentar a mitad del 2021, al mismo tiempo que se incrementaba en Estados Unidos. El hecho de que la creciente inflación haya del Covid y la respuesta política sido un fenómeno global sincronizado refleja dos causas principales, ambas directamente relacionadas con la pandemia asociada.

Los confinamientos y las restricciones de movilidad en todo el mundo tuvieron un impacto adverso en la oferta, lo que implicó graves interrupciones en las cadenas de suministro globales y el inevitable cierre de importantes sectores económicos. A la vez, en opinión del Comité el factor más importante han sido las respuestas de política fiscal y monetaria en Estados Unidos y otras economías que generaron un aumento sin precedentes en la demanda agregada. La expansión de los agregados monetarios llevada a cabo por la Reserva Federal en los primeros meses de la pandemia eclipsó las expansiones monetarias que ocurrieron en crisis anteriores, como la crisis financiera global de 2008-09.

Inicialmente y de manera similar a lo ocurrido en 2008-09, la expansión monetaria no estuvo asociada a presiones inflacionarias. En la crisis financiera global, la Reserva Federal amplió su balance para compensar la destrucción de liquidez privada que se produjo tras la caída de Lehman Brothers. En contraste, en el 2020, hubo un fuerte aumento en la demanda precautoria de dinero. Así, pese al aumento de 20 puntos porcentuales en el ratio de M2 sobre PIB, no hubo un desequilibrio evidente entre la demanda y la oferta de liquidez. En consecuencia, en los primeros meses de la pandemia, las presiones inflacionarias no se materializaron.

Sin embargo, cuando la pandemia comenzó a retroceder, la situación cambió drásticamente. La precaución que había inducido el fuerte aumento de la demanda de dinero comenzó a revertirse gradualmente, creando un incipiente exceso de liquidez en EE. UU. Además, Estados Unidos inició amplias y reiteradas expansiones fiscales. El efecto neto fue que en torno a mayo de 2021 comenzaron a surgir presiones inflacionarias, que se aceleraron a principios del 2022 y en junio alcanzaron un máximo de casi el 9% en términos anuales, la cifra más alta en más de cuatro décadas.

En un principio, no estaba claro en qué medida la inflación estaba siendo impulsada por los shocks de oferta o por el fuerte aumento de la demanda agregada asociado a las políticas monetarias y fiscales expansivas. Muchos analistas enfatizaron las interrupciones de las cadenas de suministro globales como la principal causa de la inflación y concluyeron que el fenómeno probablemente sería transitorio y que, por tanto, no era necesario adoptar una política monetaria restrictiva de inmediato. Además, después de más de una década de inflación muy baja, e incluso de presiones deflacionarias, la Reserva Federal estaba más preocupada por el potencial impacto de la normalización de políticas en el mercado laboral y la actividad económica. El resultado fue que la política monetaria en Estados Unidos y otras economías avanzadas se retrasó a la hora de responder al aumento acelerado de la inflación, mientras que los problemas por el lado de la oferta continuaban.

Estos acontecimientos tuvieron un impacto negativo en América Latina. El aumento de la inflación estadounidense se tradujo en una mayor inflación importada, debido al papel dominante del dólar en la facturación del comercio mundial. Además, los mercados internacionales de capital se comenzaron a preocupar cada vez más por la eventual necesidad de adoptar una política monetaria restrictiva en Estados Unidos, lo que provocó depreciaciones de las monedas en toda la región. A su vez, la debilidad de las monedas se sumó a las presiones inflacionarias internas.

Además de los efectos de las políticas en Estados Unidos y otras economías avanzadas, las políticas locales (que estuvieron sincronizadas) también afectaron la trayectoria de la inflación. Como en la mayoría de regiones, los gobiernos de América Latina llevaron a cabo políticas fiscales expansivas para apoyar a las empresas y los hogares durante la pandemia, aunque con grandes diferencias entre países. Estas expansiones no se revirtieron rápidamente cuando el consumo se recuperó, lo que aumentó las presiones sobre las monedas y la inflación.

2. Políticas de respuesta

A diferencia de la Reserva Federal, que reaccionó tarde a la inflación e inició su ciclo de ajuste en marzo de 2022, la respuesta de los bancos centrales de América Latina fue oportuna. El Banco Central de Brasil fue el primero en iniciar el ciclo de ajuste preventivo en mayo de 2021, seguido de México en junio, Chile en julio y Perú en agosto. La rápida reacción de los bancos centrales ante el aumento de la inflación se debió a varias razones. La combinación de una mayor inflación importada y la depreciación de las monedas llevó a los bancos centrales de la región a actuar de manera temprana y preventiva para evitar que se repitieran las costosas experiencias inflacionarias del pasado. Las políticas restrictivas también se consideraron una respuesta indispensable a la reducción de la liquidez mundial y a las presiones resultantes en los mercados de divisas. En países con fragilidades financieras, evitar depreciaciones excesivas para prevenir impactos negativos en los balances y posibles peores equilibrios puede ser deseable.

3. Perspectivas de inflación en la región y riesgos

La inflación de EE. UU. parece haber alcanzado su punto máximo, pero aún existe una gran incertidumbre sobre su persistencia y el impacto potencial de la política monetaria restrictiva en la actividad económica. La Reserva Federal proyecta llevar su tasa de política monetaria al rango de 4,5% a 5% para el 2023. Es alentador que las expectativas de inflación permanezcan bien ancladas, lo que refleja la considerable credibilidad que la Reserva Federal ha adquirido en las últimas décadas, aunque no se pueden descartar que la presencia de expectativas adaptativas (basada en información del pasado).

El Comité cree que otros factores pueden contribuir a que la inflación global se reduzca más rápido de lo previsto. En primer lugar, actualmente el ajuste monetario se está produciendo de forma simultánea en todas las regiones. En segundo lugar, el aumento de los indicadores de riesgo y los precios más bajos de los bonos del Tesoro de EE. UU. a lo largo de toda la curva de rendimiento reducen la liquidez global y el colateral disponible en los mercados internacionales de capital. En tercer lugar, el inicio de la reversión de la expansión cuantitativa (Quantitative Easing en inglés) tanto en EE. UU. como en la Eurozona ha complementado el aumento de las tasas de política monetaria.

En América Latina, el ajuste temprano de los bancos centrales parece estar logrando los resultados deseados. La inflación en Brasil se ha reducido drásticamente en los últimos meses y el país parece estar controlando la inflación sin causar una recesión por el momento. Además, en un contexto de elevados desequilibrios fiscales, la reciente respuesta monetaria demuestra la independencia de muchos bancos centrales latinoamericanos frente a presiones fiscales.

En resumen, asumiendo un escenario base en el que no se produzcan interrupciones repentinas de flujos de capital, el Comité considera que la inflación en la región puede comenzar a bajar más rápidamente en los próximos meses. Con suerte, se puede evitar un escenario que acabe con un aterrizaje forzoso. Desafortunadamente, es probable que países como Argentina y Venezuela continúen experimentando una alta inflación, lo que refleja factores idiosincrásicos y debilidades endémicas de sus políticas macroeconómicas.

4. Implicaciones para la política económica

El escenario global sigue siendo muy incierto. Si bien la inflación está comenzando a disminuir, aún es demasiado pronto para cantar victoria.

Por otra parte, las tasas de interés más altas aumentan el riesgo de que los niveles de deuda récord alcanzados en el mundo durante la pandemia puedan volverse insostenibles. Esto se refleja en los spreads de los mercados emergentes con altos rendimientos (“high yield”), que se mantienen en niveles extremadamente elevados, sólo comparables con los picos alcanzados durante la pandemia y el colapso de Lehman. Al mismo tiempo, los spreads de los activos de mercados emergentes con mejores calificaciones de riesgo (aquellos que han alcanzado grado de inversión) también han aumentado, pero bastante menos.

En este contexto, el Comité considera que los bancos centrales de América Latina deben ser cautelosos y mantener su actual postura restrictiva hasta que haya evidencia clara de que la inflación está disminuyendo. Una relajación prematura de la política monetaria puede debilitar la credibilidad que ha costado tanto lograr.

En el contexto actual de importantes salidas de capital de los mercados emergentes, las autoridades también deben prepararse para la posibilidad de interrupciones repentinas y disruptivas de los flujos de capital de los mercados internacionales. En este contexto, el Comité considera que la carga de la preparación de políticas no puede recaer exclusivamente en los bancos centrales. La política fiscal debe desempeñar un papel complementario importante, ya que son los mercados de deuda los que pueden estar sujetos a una volatilidad repentina. Tener déficits presupuestarios estructurales más pequeños y colchones de liquidez más grandes será fundamental para reducir la vulnerabilidad financiera.

Asimismo, se debe tener en cuenta que un exceso de optimismo también puede acarrear serios riesgos. El ritmo del ajuste monetario en Estados Unidos y la “huida” hacia el dólar se han acelerado desde el inicio de la pandemia y es probable que aumente la volatilidad financiera y macroeconómica global. Esto en parte ya se refleja en la alta e inesperada apreciación del dólar.

Los encargados de formular políticas se enfrentan a desafíos que no tienen un precedente histórico claro, (por ejemplo, la extrema volatilidad de los agregados monetarios de las monedas de reserva, algo no visto desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial), por lo que es poco probable que las propuestas de políticas encuentren un amplio acuerdo entre las ramas del gobierno. El Comité considera que una coordinación de políticas entre las diferentes ramas de gobierno (es decir, entre el ministerio de finanzas, el banco central, los bancos estatales y, cuando corresponda, el regulador del sistema bancario) que comience mucho antes de que sea urgente es muy deseable. Además, la confidencialidad de estas actuaciones es esencial. Sin ella, la mera discusión de escenarios de crisis puede convertirse en una profecía autocumplida y, por supuesto, contraproducente.

Como ya es ampliamente reconocido, las políticas como respuesta a la pandemia de Covid causó niveles récord de deuda pública tanto en las economías avanzadas como en los países emergentes y en desarrollo. Si bien los niveles de liquidez (en particular, las reservas internacionales) son más altos que en episodios anteriores de volatilidad en los mercados de capital, el alto endeudamiento plantea un riesgo significativo, especialmente para los mercados emergentes, como sugieren las fuertes y continuas salidas de capital de estos mercados durante 2022.

Los altos niveles de riesgo pueden ser particularmente dañinos si un evento crediticio en un mercado emergente contagia a otras economías y se vuelve sistémico. En este caso, economías que son estructuralmente sólidas pueden acabar en un equilibrio negativo. Hasta ahora, el contagio no ha ocurrido—como muestra el caso de Sri Lanka—porque los fundamentos de los países que tuvieron que reestructurar su deuda eran particularmente problemáticos, pero no eran indicativos de que hubiera problemas en otras economías. Sin embargo, como se mencionó anteriormente, las condiciones actuales del mercado y los indicadores de riesgo en países emergentes con altos rendimientos (“high yield”) y en las economías en desarrollo sólo son comparables con los que había al comienzo de la pandemia o en el colapso de Lehman en 2008. Este es un indicio claro de potenciales vulnerabilidades.

El contagio financiero puede implicar externalidades que requieran una respuesta sistémica. El Comité cree que la comunidad oficial internacional debe considerar promover acciones específicas dirigidas a reducir los niveles de deuda en los países emergentes y en desarrollo, por ejemplo, a través de recompras de deuda. En concreto, el Comité cree que, como parte de sus programas (especialmente de aquellos que requieren un acceso excepcional), el FMI debería reservar una parte de su asistencia para financiar exclusivamente recompras de deuda.

Existen dos razones importantes por las que las recompras de deuda, que además reducen la externalidad previamente mencionada, son eficientes. En primer lugar, los programas del FMI a menudo se basan en la expectativa de que su función catalizadora permitirá a los países volver a acceder al mercado de capitales y obtener el financiamiento necesario para pagar al Fondo en el futuro. Como se ha demostrado en el programa argentino, esta expectativa puede ser demasiado optimista porque los gobiernos no necesariamente toman las medidas requeridas para restaurar la sostenibilidad de la deuda y tienen un incentivo para utilizar los recursos del Fondo en el corto plazo sin tener en cuenta la carga de deuda que se traspasa a futuras administraciones. En este contexto, las recompras de deuda eluden la miopía política y abordan directamente el problema de la sostenibilidad de la deuda. En segundo lugar, en ausencia de un mecanismo eficiente para la reestructuración ordenada de la deuda soberana, las recompras de deuda impulsadas por el FMI pueden ser una herramienta eficiente para reestructurar la deuda de facto y evitar defaults y procesos de reestructuración de deuda costosos.

Finalmente, el Comité considera que, ahora más que nunca, es fundamental que la política económica sea apoyada por las autoridades políticas. Muchos países de la región están experimentando entornos políticos más polarizados y los nuevos gobiernos enfrentan desafíos económicos inusuales. Los responsables de las políticas públicas deben mantener el rumbo y esforzarse por consolidar un apoyo político de un espectro lo más amplio posible. La capacidad de aglutinar apoyo político y lograr estabilidad se ha convertido en un componente esencial para tener la confianza de los inversores y, por tanto, sostenibilidad financiera

El Comité Latino Americano de Asuntos Financieros (CLAAF) reconoce agradecidamente el apoyo financiero del Center for Global Development, el Banco Central de Chile, y FLAR por financiar sus actividades durante el 2022. El Comité agradece el apoyo de Nayke Montgomery en la producción de esta declaración. El Comité es totalmente independiente y autónomo al redactar sus declaraciones.

Esta declaración fue escrita en conjunto por:

Laura Alfaro, Profesora Warren Albert, Harvard Business School. Ex Ministra de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica, Costa Rica.

Guillermo Calvo, Profesor, Universidad de Columbia. Ex Economista Jefe, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo.

José De Gregorio, Profesor, Universidad de Chile. Ex Gobernador del Banco Central y ex Ministro de Economía, Minería y Energia, Chile.

Pablo Guidotti, Profesor, Universidad de Torcuato di Tella. Ex Viceministro de Finanzas, Argentina.

Ernesto Talvi, Investigador Senior Asociado, Real Instituto Elcano, Madrid. Ex Director Ejecutivo de CERES y ex Canciller, Uruguay.

Liliana Rojas-Suarez, Presidenta, CLAAF; Investigadora Principal y Directora de la Iniciativa Latinoamericana, Centro para el Desarrollo Global (Center for Global Development). Ex Economista Jefe para América Latina, Deutsche Bank

Andrés Velasco, Decano de la Escuela de Políticas Públicas, London School of Economics. Ex Ministro de Hacienda, Chile.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.