Recommended

This blog is one in a series by experts across the Center for Global Development ahead of the 2022 US-Africa Leaders Summit. These posts aim to re-examine US-Africa policy and put forward recommendations to deliver on a more resilient, deeper, and mutually beneficial partnership between the United States and the nations of Africa.

The US-Africa Leaders Summit in Washington, DC presents an important opportunity to discuss the public good provided by African countries in hosting 7 million refugees. The US is the largest bilateral and multilateral donor to refugee responses around the world. However, with a record number of people displaced, more must be done to advance development-led approaches that recognize the reality of protracted displacement, harness the productive potential of refugees to support themselves and local economies, and respond to the shared challenges of hosts and refugees.

One critical tool that African and US officials should focus on and jointly advocate for is the World Bank’s Window for Host Communities and Refugees (WHR). Designed as an innovative financing mechanism, the WHR provides funding incentives for low-income countries to include refugees in poverty reduction efforts and other development programs and has a review framework to monitor and promote improvements in refugee policy. To date, 77 percent of the WHR has been committed to African countries, which host 72 percent of refugees who live in low-income, eligible countries.

As the largest shareholder of the World Bank (and with its recent replenishment pledge, the largest contributor to the bank’s concessional window), the US has a strong interest in ensuring the WHR provides the support host countries need to deliver positive development outcomes for host communities and refugee populations alike. And, in an era of squeezed aid budgets, multilateral development banks (MDBs) like the World Bank offer donors leverage: for every US$1 from the United States, the World Bank can provide an additional $4 to low-income countries.

Building on its strong partnerships with country governments, focus on poverty reduction, and multi-year funding, the World Bank can more effectively support medium-term approaches such as including refugees in health and education systems (versus parallel systems) and job creation programs. For a number of African leaders, the $2.4 billion WHR is a major source of funding that is linked to their country’s development plans, in contrast to the vast majority of humanitarian aid that directly targets refugee subsistence.

Background on the World Bank’s Window for Host Communities and Refugees

The International Development Association (IDA) is the World Bank’s main tool for supporting low-income countries with concessional financing, offering low- to no-interest rate loans and grants across a variety of sectors. In 2016, the World Bank launched the $2 billion Regional Sub-Window for Refugees and Host Communities (RSW) as part of the IDA’s 18th Replenishment. The RSW lasted for three years, until June 2020, when it was redesigned as the $2.2 billion Window for Host Communities and Refugees (WHR) as part of IDA19. (IDA19 covered two, rather than three, years due to the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore only allocated $1.3 billion of the total.) The WHR continues under IDA20 with $2.4 billion in funding.

The WHR and its predecessor the RSW were created in recognition of the fact that low-income countries that host refugees often struggle to meet their development goals for their own citizens. Humanitarian and development assistance must reach both host communities and refugee populations to move beyond care and maintenance aid approaches and improve social cohesion. The WHR provides additional financing beyond the country’s typical IDA allocation, and for most countries, does so on even more favorable terms. WHR funding supports refugee-hosting countries to mitigate shocks and create social and economic development opportunities for refugees and hosts; facilitate the social and economic inclusion of refugees in host countries and/or as returnees; and strengthen country preparedness for additional refugee flows.

The country eligibility criteria include hosting at least 25,000 refugees (or refugees make up at least 0.1 percent of the population), having a minimally adequate framework for refugee protection, and an action plan for longer-term development solutions that benefit refugees and host communities. Once a country becomes eligible, individual projects are reviewed and cleared for WHR funding by World Bank management before submission to the board for approval. Projects are expected to include efforts to improve the policy and institutional environment for refugees.

In the most recent IDA replenishment—IDA20—the World Bank committed to achieving significant policy improvement and implementation in at least 60 percent of beneficiary countries eligible for the WHR and also added new language on the importance of policy dialogue. For example, among priority activities, it highlights “support legal solutions and/or policy reforms with regard to refugees, e.g., freedom of movement, formal labor force participation, identification documents, and residency permits.”

In order to track progress, the World Bank developed the Refugee Policy Review Framework (RPRF). The framework outlines four dimensions—host communities, regulatory environment and governance, economic opportunities, and access to services—and a methodology. The first review was released in 2021 and provided detailed narratives on all dimensions for the 14 eligible countries at the time of writing. The review finds a “significant impetus for reforms,” especially at the early stages of IDA18, but noted that progress slowed amid the COVID-19 pandemic and varies significantly across contexts. For IDA20, the RPRF will be used to determine if the WHR meets its 60 percent target for significant policy improvement.

WHR funding for Africa

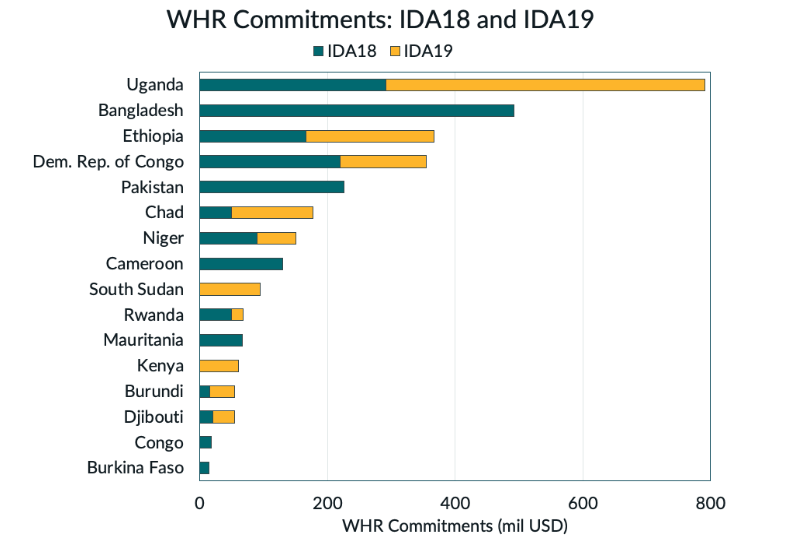

To date, 15 of the 17 countries that have benefitted from the WHR are in Africa: Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Mauritania, Niger, Republic of Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Uganda. In addition, Bangladesh and Pakistan have received support.

Funding is notionally allocated to countries based on the number of refugees hosted, and the amounts that are eventually committed also depend on country demand, specific project due diligence approval, and other factors. Uganda, which hosts the most refugees in Africa, has received the most, including the maximum of $500 million in IDA19.

WHR funds have been used on a variety of projects on the continent. RSW funding in Chad incentivized and supported the country’s first-ever national refugee policy that reflects the rights of refugees as laid out in the 1951 Refugee Convention. The World Bank recently approved budget support to Liberia, including resources from the WHR, based on policy reforms which include an increase in refugees' access to public services. South Sudan has used WHR funds to improve the socioeconomic conditions of refugees and host communities by providing critical services like basic health care, COVID-19 vaccines, clean water, and education for youth.

Recommendations to increase the WHR’s impact

US and African leaders should discuss successes of the WHR to date and commit to support ideas to increase its impact. Areas for discussion should include:

- Expanding the size of the WHR and assessing the levels of concessionality. An additional four countries joined the pool of eligible countries between IDA19 and IDA20, but funding for the window increased only modestly. The World Bank and its partners should assess opportunities to increase the size of the WHR both during the mid-term IDA assessment (when funds can be reallocated based on obligations and need) and in the next round of fundraising for IDA. As part of discussions on reforming and expanding MDBs to provide global public goods, IDA contributors including the US should consider the levels of concessionality offered through the WHR. It will be important to balance levels that incentivize country demand, appropriate recognition of the public good component (with many benefits accruing to others in the region and the world), and the need to preserve the leverage of donor dollars.

- Aligning US and other bilateral funding with WHR investments: At the summit, the US could commit to co-financing WHR projects through USAID and/or State. Aligning and crowding in bilateral funding would increase the program reach and policy impact of WHR projects. As the leading donor in refugee response, the US should also work with other bilateral donors to encourage co-financing.

- Executing on the increased focus on policy reforms, especially those that facilitate refugee economic contributions. The core promise of the WHR is that it provides an infusion of resources toward realizing the development potential of hosts and refugees. For example, the upfront costs of including refugees in education and health systems is both more efficient than creating parallel systems and yields longer-term and sustainable benefits as refugees contribute to local economies. However, these benefits only accrue if refugees are offered meaningful de jure and de facto opportunities to make these contributions. Recognizing the political sensitivity of refugee work in many contexts, the WHR has made significant progress, but more attention is required. For African countries, it is critical to make de facto reforms and track implementation progress at the local level, because funders need to see results that development carrots can actually work. US policymakers must make their support for these reforms clear at the summit and beyond, through continued diplomatic engagement on the rights of refugees across bilateral and multilateral fora.

- Considering independent de jure and de facto policy assessments in addition to the RPRF, and linking policy assessment to financing allocations. The WHR should increase transparency and coordination around discussions of each country’s Refugee Policy Review Framework, and how the RPRF is connected to negotiations around specific programs funded by the WHR. In addition the World Bank should consider linking policy and implementation to concessional finance allocations, so that countries with the most inclusive practices receive more per refugee hosted..

- Promoting WHR-like tools and approaches at other MDBs and donors. The World Bank has led on the agenda of recognizing refugee hosting as a global public good, supporting development outcomes to complement humanitarian relief, and creating financial instruments to respond. The World Bank also hosts a trust fund, the Global Concessional Financing Facility, that includes other MDBs and supports middle-income countries hosting refugees. However, the contributions are ad hoc and insufficient to meet current needs. The Inter-American Development Bank has a dedicated migration program with strong leadership, but also requires additional and predictable funding. Other MDBs—including big players in Africa like the African Development Bank and the Islamic Development Bank—should learn lessons from the WHR and develop robust, development-focused instruments to provide greater support to refugee-hosting countries in their regions. The United States is a leading shareholder in almost all MDBs, and concerted US leadership to elevate such instruments could yield dividends for both displaced persons and the communities that host them. For these tools to meet their potential, they require predictable funding at levels that can meaningfully shape a country’s approach.

- Elevating in-country coordination and consultations, including refugee and host community leaders, on the RPRF and WHR programs. Currently, the World Bank and UNHCR are systematically engaged in WHR discussions with country governments, but inclusion of other key stakeholders occurs on an ad hoc basis. The US should ensure engagement of relevant embassy staff in country dialogues to support joint prioritization and co-financing, and as mentioned above, encourage the participation of other bilateral donors. African leaders can support greater coordination across affected ministries, recognizing that support for host communities and refugees crosses sectors. Finally, all parties should work to deepen the engagement of refugees and host community members in policy and program discussions. For example, country-level coordination platforms could host regular consultations with refugee and host organizations, ensuring that convenings are substantive and tailored to facilitate participation.

Conclusion

In October, Secretary Yellen called for reforming and expanding the MDBs to address global public goods in addition to country development priorities. For African leaders of refugee-hosting countries and US officials, the WHR, as a unique tool to provide significant development financing for a global challenge, should be a high priority for discussion.

The authors thank Cassie Zimmer, Jocilyn Estes, Erin Collinson, Clemence Landers, and Sarah Miller for their input.

Stay tuned for more analysis on the summit in the coming days, and sign up for our US development policy newsletter to get updates in your inbox.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Miros / Adobe Stock