Brazil’s newly elected President Jair Bolsonaro has been characterised as an unsavoury anti-globalist—so, will he unwind Brazil’s progress as a development actor over the last two decades? Below, I will highlight Brazil’s important contributions to international development, and argue that Bolsonaro’s best bid to eliminate corruption, restore trust in government institutions, and reinstate the country’s path of prosperity is to finalise Brazil’s OECD membership—becoming its second biggest member by population—while also strengthening partnerships and commitments to fast growing markets in the Global South.

Bolsonaro takes charge with a nationalist and anti-corruption agenda

On October 28, citizens in Brazil went to the polls to elect their new president in a run-off election. Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) won 55.1 percent of the vote and on January 1, 2019, he will replace Michel Temer, who is leaving office with current approval ratings of just 2 percent. Far-right Bolsonaro (Video portrait NYT) has won a lot of support among people fed up with escalating criminality and staggering corruption among high-level politicians, including former president Lula da Silva.

After years of domestic political turmoil and economic deadlock, Brazil has the opportunity to relaunch its foreign policy and role in the global economy (CFR, 2017). Yet, Bolsonaro appears to be an anti-globalist at heart (ISPI, 2018). While still little is known about Bolsonaro’s true intentions regarding Brazil’s foreign relations, he campaigned on slogans suggesting a downright retreat from international commitments and a strong focus on domestic policies.

The evolution of Brazil’s role in international development

Brazil has stepped up its role in international development over the last 20 years, especially during the presidency of Lula da Silva of the Workers Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT), from 2003–2011. While most people probably associate Brazil with its influential United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992 (Earth Summit) and the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), it has also been growing its presence in other areas regarding international commitments to development like research cooperation and peacekeeping operations.

It was mainly former president Lula da Silva who set up a new and ambitious strategy in supporting other developing countries in its economic and social progress. Its aim was to establish and pursue a distinct “South-South Co-operation” (SSC), as it is also promoted by other BRICS countries which include China, India, and South Africa. Brazil’s Cooperation Agency (ABC – Cooperaçao Técnica Brasileira) states that its cooperation is demand-driven and “offers solutions tailored to beneficiaries’ needs” (Cabral et al. 2014).

Aid, in the sense of traditional DAC donors, has not been a primary aim of Brazilian development cooperation. Brazil is characterized as a partner rather than a donor and has been a recipient of Official Development Assistance (ODA) over many years. By 2013, Brazil’s development cooperation was present in 159 countries, totalling an overall disbursement of about 1.5 billion USD from 2011–2013. Fifty-three percent of funds is spent on contributions to international organizations. Regional, historical, and cultural ties to former Portuguese colonies and to Latin American countries drive Brazil’s technical cooperation (Semrau and Thiele, 2017).

In 2013, Brazil spent about $23 million USD on educational cooperation, which primarily supports foreign students to study in Brazil. It invested 1.66 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on science and technology cooperation, and had a similar level of spending on R&D as Russia (1.12 percent) and Italy (1.26 percent), but far from countries such as such as China (2.08 percent) or Germany (2.85 percent) (IPEA, 2017). The focus is on supporting a wide range of research collaborations and joint laboratories, especially in agriculture (e.g., the Embrapa-Labex programme).

Brazil’s humanitarian cooperation commitment is shown by agreements and partnerships with international organisations to deal with food and nutritional security hazards, risk management, disaster risk reduction, and also the support for refugees (IPEA, 2017). Brazil’s refugee protection legislation demonstrates its strong belief in the multilateral rules framework and the protection of human rights. Recently, Brazil took a leading role in accepting thousands of Venezuelan refugees (56,000 since 2014) that have been fleeing from an ongoing economic crisis and political turmoil. President-elect Bolsonaro, however, assured to make border policies towards Venezuela more restrictive (AS/COA, October 18, 2018).

Brazil actively supports peacekeeping operations and its institutional foundations. According to IPEA (2017), the design of the UN Peacebuilding Commission (CCP) was strongly influenced by Brazil. In 2016 Brazil contributed financial resources of $55.9 million USD to UN Peacekeeping operations, comparable to countries like Denmark and Austria. Brazil deployed 1,729 armed forces personnel in UN peacekeeping missions in 2013 , making it 19th among the 122 countries that were contributing troops (IPEA 2017), a number that is down to currently 274 (48th).

Will Brazil’s trade relationships shape its international commitments?

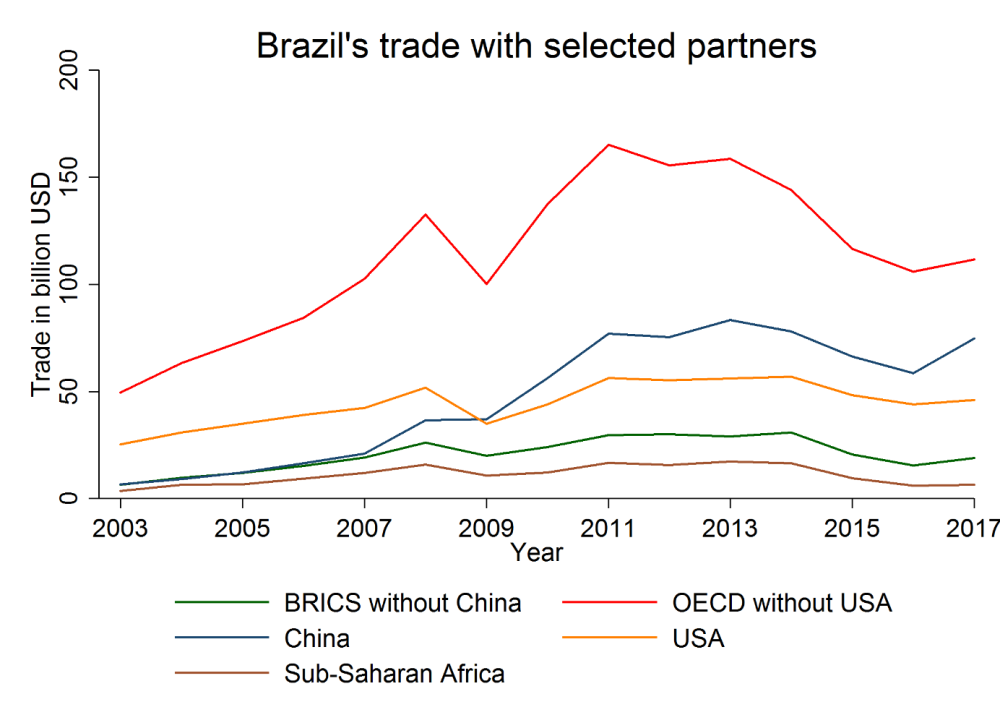

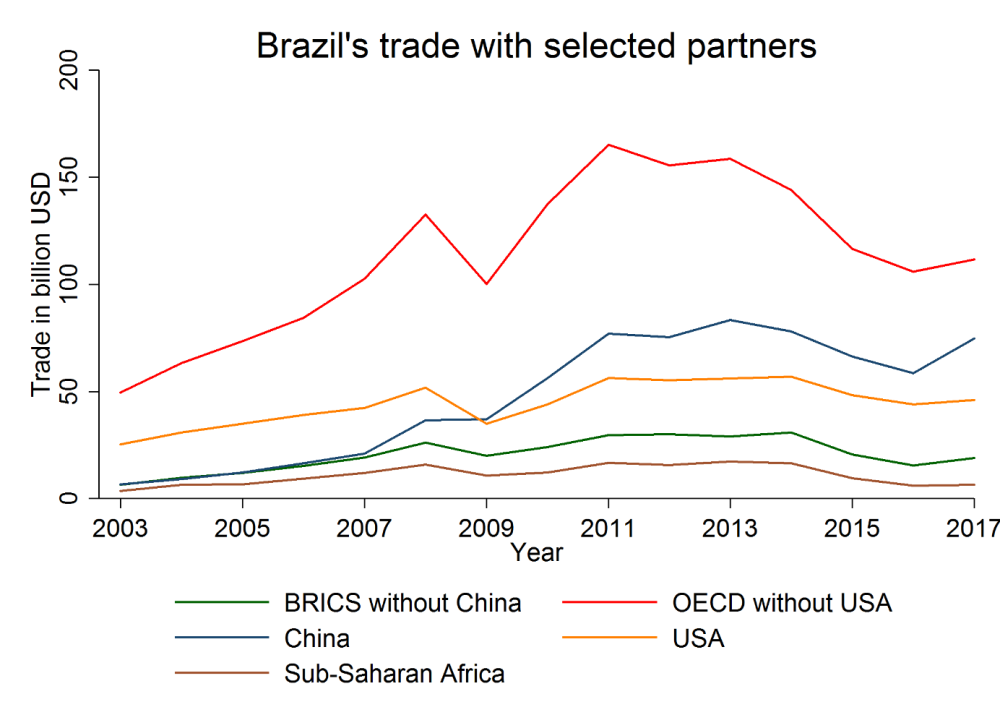

Brazil’s trade relationships will be important to re-establish the country on a path of growth and prosperity. Figure 1 below plots total trade of Brazil with selected trading blocs. OECD countries are by far the largest trading partners (even if the US is subtracted). Brazil became a key partner of the OECD in 2007 and has intensified cooperation ever since. It requested to become a full OECD member in June 2017.

OECD membership is not only likely to foster trade and bolster investment, but would also have beneficial effects on other aspects of Brazil’s economy and governance. In particular, the OECD uses specific instruments to fight transnational corruption, implemented in the OECD Anti-Bribery convention of which Brazil is already a party. It would further improve the business environment, tax compliance, and help to establish an effective and sustainable pension system. Such steps would all be in line with Bolsonaro’s pledge to fight corruption and support for a more efficient government administration.

Brazil’s single most important trading partner is China. Even trade with all Mercosur countries (Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay) is lower than trade with either China or the United States. How Bolsonaro will treat Brazil’s relations with China is both important and hard to predict. Given the importance of China as a trading partner—and particularly for Brazil’s agricultural sector that supported his campaign—Bolsonaro will thus likely be cautious in making bold decisions regarding the BRICS association despite him insinuating to withdraw Brazil from the association (AS/COA, October 18, 2018).

Dismantling Brazil’s commitment towards the BRICS might jeopardize trade relations with China and gave China even more weight and influence within the association. Brazil, together with its democratic partners, India and South Africa, institutionalized in the IBSA Dialogue Forum, would do good to balance the power of the authoritarian regimes within the BRICS, China, and Russia.

Figure 1. Brazil’s Trade with Select Partners, 2003-2017 (USD billions)

Note: figure depicts total trade (exports + imports) in USD with selected trading partners. Source: WITS

Former president Lula da Silva’s legacy of strengthening ties with lower income countries especially in sub-Saharan Africa is likely most at risk. Neither Bolsonaro’s nationalistic rhetoric nor commercial interests seem to suggest that he has any interest in strengthening these partnerships, which have been an important part of Brazil’s development cooperation. Trade with sub-Saharan countries is still low and decreased further during Brazil’s economic crisis.

Despite his offensive statements, Bolsonaro pledges to be both democratic and constitutional in his leadership (Watch his victory speech). It remains to be seen whether he will protect values enshrined in the constitution that highlight cooperation among peoples for the progress of humanity. The international community and people of Brazil should make every effort to keep him accountable on these terms.

El recién elegido presidente de Brasil, Jair Bolsonaro, se ha caracterizado por ser un antiglobalista desagradable, por lo tanto, ¿desentrañará el progreso de Brasil como actor del desarrollo en las últimas dos décadas? A continuación, resaltaré las importantes contribuciones de Brasil al desarrollo internacional y sostendré que la mejor oferta de Bolsonaro para eliminar la corrupción, restablecer la confianza en las instituciones gubernamentales y recuperar el camino de prosperidad del país es finalizar la adhesión de Brasil a la OCDE, convirtiéndose en el segundo mayor Estado Miembro en términos de población, y al mismo tiempo fortalecer asociaciones y compromisos con mercados de rápido crecimiento en el Sur Global.

Bolsonaro toma el control con una agenda nacionalista y anticorrupción

El 28 de octubre, los ciudadanos de Brasil acudieron a las urnas para elegir a su nuevo presidente en una segunda vuelta electoral. Jair Bolsonaro del Partido Social Liberal (PSL) obtuvo 55,1 por ciento de los votos y, el 1 de enero de 2019, reemplazará a Michel Temer, quien dejará el cargo con índices de aprobación actuales de solo 2 por ciento. Bolsonaro, de la extrema derecha (Retrato de video de NYT) ha ganado mucho apoyo entre personas que están hartas de una criminalidad creciente y una tremenda corrupción entre políticos de alto nivel, incluido el expresidente Lula da Silva.

Después de años de agitación política interna y de un estancamiento económico, Brasil tiene la oportunidad de reactivar su política exterior y su papel en la economía global (CFR, 2017). Sin embargo, el nuevo presidente electo de Brasil, Jair Bolsonaro, parece ser un antiglobalista de corazón (ISPI, 2018). Si bien aún se sabe poco acerca de las verdaderas intenciones de Bolsonaro con respecto a las relaciones exteriores de Brasil, hizo campaña con lemas que sugieren una retirada total de los compromisos internacionales y un fuerte enfoque en las políticas nacionales.

La evolución del rol de Brasil en el desarrollo internacional

Brasil ha intensificado su rol en el desarrollo internacional en los últimos 20 años, especialmente durante la presidencia de Lula da Silva del Partido de los Trabajadores (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT), de 2003 a 2011. Si bien la mayoría de las personas probablemente asocian a Brasil con su influyente Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Medio Ambiente y el Desarrollo en 1992 (Cumbre de la Tierra) y la Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Desarrollo Sostenible (Río+ 20), también ha aumentado su presencia en otras áreas con respecto a los compromisos internacionales en materia de desarrollo como cooperación en investigación y operaciones de mantenimiento de la paz.

Fue principalmente el expresidente Lula da Silva quien estableció una nueva y ambiciosa estrategia para apoyar a otros países en desarrollo en el progreso económico y social. Su objetivo era establecer y perseguir una “Cooperación Sur-Sur” (SSC) distinta, ya que también es promovida por otros países BRICS que incluyen China, India y Sudáfrica. La Agencia de Cooperación de Brasil (ABC - Cooperaçao Técnica Brasileira) afirma que su cooperación está impulsada por la demanda y "ofrece soluciones adaptadas a las necesidades de los beneficiarios" (Cabral et al. 2014).

La ayuda, en el sentido de los donantes tradicionales del CAD, no ha sido un objetivo primordial de la cooperación brasileña para el desarrollo. Brasil se caracteriza como un socio en lugar de un donante y ha sido receptor de Ayuda Oficial al Desarrollo (AOD) durante muchos años. Para 2013, la cooperación para el desarrollo de Brasil estaba presente en 159 países, con un desembolso total de alrededor de 1.500 millones de dólares estadounidenses entre 2011 y 2013. El 53% de los fondos se gasta en contribuciones a organizaciones internacionales. Los lazos regionales, históricos y culturales con las antiguas colonias portuguesas y los países latinoamericanos impulsan la cooperación técnica de Brasil (Semrau y Thiele, 2017).

En 2013, Brasil gastó alrededor de $23 millones de dólares en cooperación educativa, que principalmente ayuda a los estudiantes extranjeros a estudiar en Brasil. Invirtió 1.66 por ciento del producto interno bruto (PIB) en cooperación en ciencia y tecnología, y tuvo un nivel de gasto en I&D similar al de Rusia (1,12%) e Italia (1,26%), pero lejos de países como China (2,08%) o Alemania (2,85%) (IPEA, 2017). El objetivo es apoyar una amplia gama de colaboraciones de investigación y laboratorios conjuntos, especialmente en agricultura (por ejemplo, el programa Embrapa-Labex).

El compromiso de cooperación humanitaria de Brasil se demuestra mediante acuerdos y asociaciones con organizaciones internacionales para abordar los peligros de la seguridad alimentaria y nutricional, la gestión de riesgos, la reducción del riesgo de desastres y también el apoyo a los refugiados (IPEA, 2017). La legislación sobre protección de los refugiados de Brasil demuestra su firme creencia en el marco de las normas multilaterales y la protección de los derechos humanos. Recientemente, Brasil asumió un papel de liderazgo en la aceptación de miles de refugiados venezolanos (56.000 desde 2014) que han estado huyendo de una crisis económica en curso y de la agitación política. Sin embargo, el presidente electo de Bolsonaro aseguró hacer las políticas fronterizas hacia Venezuela más restrictivas (AS / COA, 18 de octubre de 2018).

Brasil apoya activamente las operaciones de mantenimiento de la paz y sus fundaciones institucionales. Según IPEA (2017), el diseño de la Comisión de Consolidación de la Paz (PCC) de las Naciones Unidas se vio fuertemente influenciado por Brasil. En 2016, Brasil aportó recursos financieros de $55.9 millones de dólares a las operaciones de mantenimiento de la paz de la ONU, comparables a países como Dinamarca y Austria. Brasil desplegó 1,729 miembros del personal de las fuerzas armadas en las misiones de mantenimiento de la paz de la ONU en 2013, convirtiéndose en el 19º país entre los 122 miembros que aportaron tropas (IPEA 2017), un número que actualmente se reduce a 274 (48º).

¿Las relaciones comerciales de Brasil darán forma a sus compromisos internacionales?

Las relaciones comerciales de Brasil serán importantes para restablecer el país en un camino de crecimiento y prosperidad. La Figura 1 representa el comercio total de Brasil con bloques comerciales seleccionados. Los países de la OCDE son, con ventaja, los socios comerciales más grandes (incluso si se restan los EE. UU.). Brasil se convirtió en un socio clave de la OCDE en 2007 y desde entonces viene intensificando la cooperación. Solicitó convertirse en miembro pleno de la OCDE en junio de 2017.

La membresía de la OCDE no solo fomentará el comercio y reforzará la inversión, sino que también tendrá efectos beneficiosos en otros aspectos de la economía y la gobernanza de Brasil. En particular, la OCDE utiliza instrumentos específicos para combatir la corrupción transnacional, implementada en la Convención Anti-Cohecho de la OCDE de la que Brasil ya es parte. Mejoraría aún más el entorno empresarial, el cumplimiento fiscal y ayudaría a establecer un sistema de pensiones eficaz y sostenible. Todos estos pasos estarían en línea con el compromiso de Bolsonaro de combatir la corrupción y apoyar una administración gubernamental más eficiente.

El socio comercial más importante de Brasil es China. Incluso el comercio con todos los países del Mercosur (Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay) es más bajo que el comercio con China o con los Estados Unidos. La forma en que Bolsonaro tratará las relaciones de Brasil con China es importante y difícil de predecir. Dada la importancia de China como socio comercial, y en particular para el sector agrícola de Brasil que apoyó su campaña, Bolsonaro probablemente será cauteloso al tomar decisiones audaces con respecto a la asociación BRICS, a pesar de que insinúe el retiro de Brasil de la asociación (AS / COA, 18 de octubre de 2018).

La retirada de Brasil de los BRICS podría poner en peligro las relaciones comerciales con China y le dio a China aún más peso e influencia dentro de la asociación. Brasil, junto con sus socios democráticos, India y Sudáfrica, institucionalizados en el Foro de Diálogo de IBSA, haría bien en equilibrar el poder de los regímenes autoritarios dentro de los BRICS, China y Rusia.

Figura 1. Comercio de Brasil con Socios Seleccionados, 2003-2017 (miles de millones de dólares)

Nota: la figura muestra el comercio total (exportaciones + importaciones) en USD con socios comerciales seleccionados. Fuente: WITS

El legado del expresidente Lula da Silva de fortalecer los lazos con los países de bajos ingresos, especialmente en el África subsahariana, es el que corre más riesgo. Ni la retórica nacionalista de Bolsonaro ni los intereses comerciales parecen sugerir que tenga interés en fortalecer estas asociaciones, que han sido una parte importante de la cooperación para el desarrollo de Brasil. El comercio con los países subsaharianos sigue siendo bajo y disminuyó aún más durante la crisis económica de Brasil.

A pesar de sus declaraciones ofensivas, Bolsonaro se compromete a ser democrático y constitucional en su liderazgo (Vea su discurso de victoria). Queda por ver si protegerá los valores consagrados en la Constitución que destacan la cooperación entre los pueblos para el progreso de la humanidad. La comunidad internacional y el pueblo de Brasil deben hacer todos los esfuerzos posibles para mantenerlo responsable en estos términos.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.