Recommended

This blog first appeared on VoxDev and is reposted with permission.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that over 105 million people are displaced by conflict worldwide. The effect of forced migrants on host populations is a crucial question for both policymakers and academics, and a substantial literature has focused on the effect of the displaced on labour markets. Effects on public services, however---where the government controls supply---have received less attention. Since 29% of the displaced are of schooling age, the impacts on education are first-order.

Conceptually, refugees’ impact on hosts’ education is not clear. First, refugees may spread the same educational inputs like schools, teachers, and classrooms across more students, but they also could bring in additional resources, especially through the foreign aid response to refugees. Second, refugee students may affect their peers within classrooms either positively or negatively. Third, refugees in the labour market may change the returns to education, as Tumen (2018) finds in Turkey. Less educated groups in Turkey faced more competition for work from Syrians, and so hosts responded by acquiring more education.

The case of Jordan

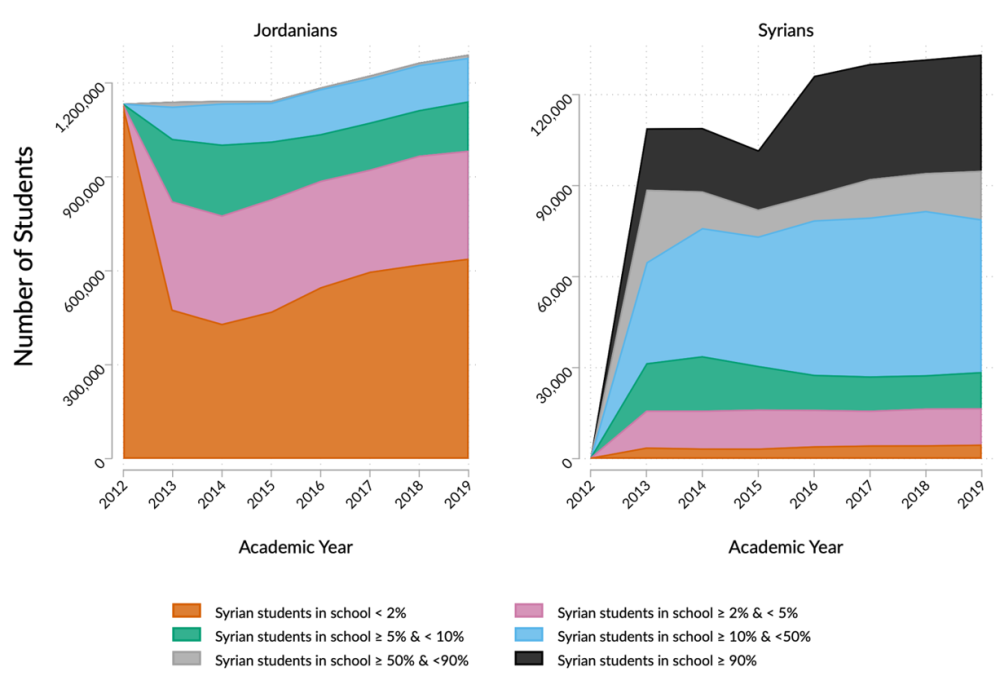

In our paper that was recently published by the Journal of Development Economics, we study this question in the context of Syrian refugees in Jordan. Almost immediately, Jordan allowed Syrians to attend school, and between the school years beginning in 2012 and 2013, the number of Syrians in Jordanian public schools increased from 558 to 108,913 (Figure 1). Since then, Syrians have represented around 7% of public school students, equal to the proportion of Syrians in the population overall. Syrians mostly concentrated in a few areas; about 92% of Syrians resided in four of twelve governorates.

Figure 1: Distribution of Jordanian and Syrian Students by the Proportion of Syrian Students

The effect of immigrants in any context depends critically on the policy environment. In this context, the Jordanian government responded to the inflow by opening second shifts in many affected areas. This policy largely insulated Jordanian students from much exposure to Syrians. Figure 1, for instance, shows that only 12% of Jordanians were in schools with more than 10% Syrians. Nevertheless, the opening of a second shift or other factors discussed above could still have affected Jordanians’ educational attainment.

Estimating the impact of refugees

Isolating the causal impact of Syrian refugees on Jordanians presents multiple challenges. If Syrians choose to live in poorer neighborhoods, for instance, comparing schools with and without Syrians would be misleading. Similarly, many other factors also affected trends over this period in Jordan, so before and after comparisons would also not isolate the effect of refugees. We therefore use a difference-in-differences design, where we compare students in affected schools to older cohorts who attended the same schools just before Syrians arrived. We then use the difference between the old and young cohorts in schools that were less affected by Syrians to account for any national time trends that were not plausibly driven by Syrian refugees.

We leverage two detailed data sources. For educational outcomes, we use the 2016 wave of the Jordan Labor Market Panel Survey, a nationally representative household survey that contains a wide range of educational outcomes for all individuals in the sample. For school-level exposure to Syrians, we use school censuses from 2011 to 2019 from the Education Management Information System (EMIS) administrative data. These report the number of students by nationality, teachers, and classrooms in each shift, school, and grade level. We merge these datasets to obtain the prevalence of Syrians in any individual’s basic and secondary school.

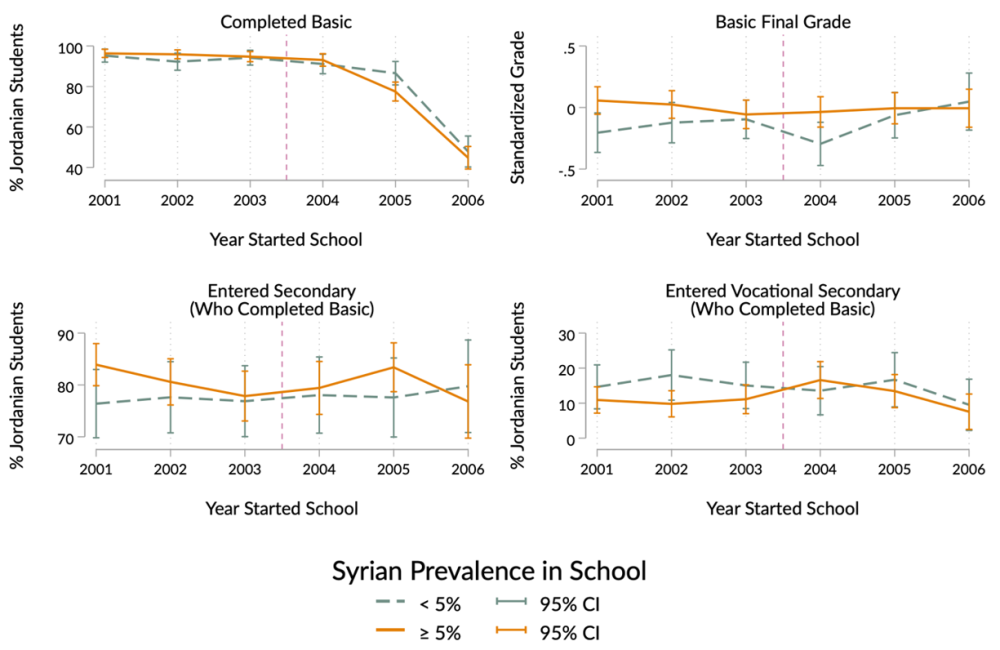

Across a range of outcomes on both the quantity and quality of education, we fail to find convincing evidence that Syrian refugees affected Jordanians’ educational outcomes. In fact, many important coefficients are positive but insignificant, so we are often able to reject the hypothesis of large negative effects. This null finding is robust across different outcomes, econometric specifications, and measures of exposure to Syrians, including at the grade or shift level. Figure 2 illustrates the minimal changes before and after Syrians and across high- and low-prevalence schools.

Figure 2: Outcomes over time by Syrian prevalence

These null results represent the overall effect that combines changes in the demand from the larger population of students with changes in the supply from the government opening second shifts, hiring teachers, etc. We are unable to separate the effects of demand and supply, but we can document the supply response. We find that in areas with more Syrians, the government opened significant numbers of new shifts and new schools. They hired new teachers and opened new classrooms, such that the student-teacher ratio and classroom density for Jordanians was largely unchanged. We run simulations that show if this supply response had not occurred, these inputs for Jordanians in the most exposed areas would have changed significantly.

Policy implications

Overall, these results suggest that one reason for the null effect is the response of the Jordanian government and the foreign donors that funded these efforts. The effects of refugees in any context depend on policy, and this context shows that more inclusive policies do not mechanically lead to more negative effects on hosts. In this case, local policymakers allowed refugees to attend local public schools with minimal barriers, and foreign donors allocated resources to cover the resulting shortfalls. More broadly, the concept also potentially applies to other controversial policies like labour market access and freedom of movement. Inclusive policies are critical for refugees’ well-being and have been affirmed repeatedly in international law. Research is needed across different policy environments and outcomes to identify any losers and allocate resources to potential solutions.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: DFID Flickr