September 23, 2008

This is a joint posting with Luke EasleyIn August, CDC released updated estimates of HIV Infection in the U.S. showing that incidence for 2006 and over the previous decade was 40% higher than previously estimated. This was big news on the eve of the Mexico City AIDS Conference, but made more news on September 17th, when CDC officials "at a House Government Reform and Oversight Committee hearing said they would need an additional $4.8 billion dollars over the next five years to reduce the annual number of new HIV infections in the U.S." The LA Times reports that:

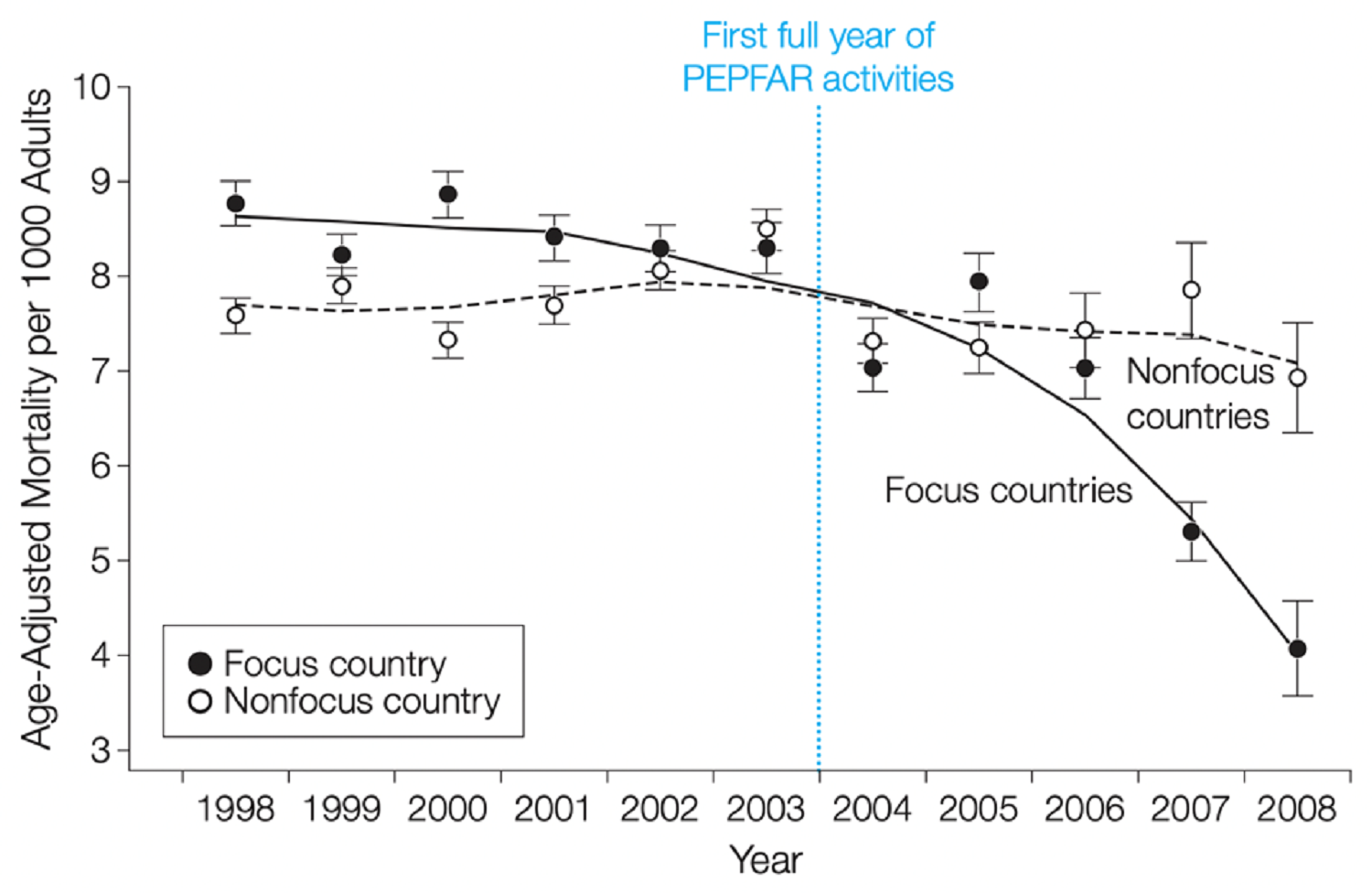

The new numbers, published last month in the Journal of the American Medical Assn., were found through improved testing and were not an increase in new infections, which have remained relatively constant since the late 1990s. The higher estimates, however, served as a reminder that preventing transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus is still an issue in the United States, where the prevalence of HIV is greater than in Canada, Australia, Japan or any Western European country except Switzerland.Sound familiar? Prevention of HIV transmission was NOT the strongest component of the United States' fantastically generous PEPFAR program overseas (see my colleague David Wendt's blog) AND it doesn't seem to be doing the trick at home either. As the LA Times reports: "Young black gay men have been especially hard hit, representing 48% of new infections among gay and bisexual males ages 13 to 29. Yet only four of the CDC's 49 recommended intervention programs specifically target gay men, and only one of them is designed to address gay men of color."Our nation's capital has been particularly hard-hit by HIV, with a prevalence rate of 5%. That's the same as the prevalence rate for sub-Saharan Africa as a whole and comparable to Uganda's most recent estimate of 5.4%. To understand this better, see what my colleague Luke Easley has to say about the trends in behaviors and prevention interventions as a voluntary HIV testing counselor reaching out to one of the most affected communities in the District of Columbia:

Being an HIV testing counselor in a U.S. city with a staggering rate of infection I've noticed some parallels with the epidemic in the developing world. Several times a month I drive a mobile testing unit, targeting areas where high risk groups congregate. My 'beat' usually takes me to places populated by young African-American males, especially men having sex with men (MSM). The well-known risk factors are still present, and I still get a knot in my stomach when a young man comes into the van with a history of substance abuse and multiple sex partners. I've become all too aware of the people who are most likely to leave the van forever changed.Recently, the clinic I serve reported a phenomenal increase in year-over-year new HIV diagnoses. Without any significant increase in the number of tests administered, the numbers are a sobering look at how we are failing to reach many people who are at high risk for contracting the virus. I realize I know only a little; the nature of this disease is so complex that even experts seem to offer many different views. I am seeing one alarming trend, however. For years now, part of my outreach to MSM has included a frank dialogue on risk-reduction. Use condoms. Limit your partners. Don't have sex while intoxicated. Know your partners. Avoid anonymous encounters. Despite this, one specific scenario is being related to me by those testing positive with an increasing frequency. The person testing positive is in a long-term relationship, but also has long-term, concurrent sexual partners on the side. These 'buddies' in many cases have been having sex with one another for months or years, know each other well and may even share activities together outside the bedroom. A level of trust between concurrent sexual partners builds with each encounter. Many rationalize that they've been tested several times since the concurrent relationship began, and the result was always negative. Condom use stops. Risky behaviors increase. Then they are sitting next to me in shock having learned their antibody test was reactive. They wonder how this happened. They aren't having sex in bathhouses, and they know every partner they have had since their last test. This route of transmission is especially troublesome because it seems to be born of a sincere desire to lessen risk of exposure to the virus.Sound familiar again? Concurrent sexual partnerships are fueling HIV infection in Africa - much has been written about this by Helen Epstein and others so I won't dwell on this issue except to make the comparison that like the U.S. global response, the U.S. domestic response to HIV has failed to recognize and respond to some key drivers of infection among the most vulnerable groups i.e. sexual behavior. The response has to move beyond "preventing" sexual behavior (abstinence) to preventing HIV transmission, and this is when domestic meets global. There is a lot to discuss here with many complexities about why the U.S. is different from Africa, and of course it is, but the parallels between the domestic and global response are perhaps a reminder that the U.S. domestic public health scene is part of the global health world AND that unsafe sexual activity is sexual activity wherever it takes place. The key issue is to address it, not avoid it.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.