News broke last week that indicated the US Supreme Court is likely to strike down Roe v. Wade, a 50-year-old precedent protecting the right to abortion. If the court’s final opinion reflects what the current draft does, it will mean that women in the United States have less legally protected bodily autonomy at the national level, despite that fact that most US citizens support protecting the right to safe abortion.

Earlier this year, as states around the country proposed and passed legislation restricting abortion access, Shelby Bourgault and I took a look at where the US sits relative to countries globally on this issue. Two key findings emerged from our review.

First, while the United States is regressing, other countries are advancing: the global trend has overwhelmingly been that of liberalization of abortion laws, with 18 countries overturning complete bans on abortions and 15 countries reforming laws to allow abortion upon request over the past 25 years. This year alone, we have seen progress on abortion rights in Argentina, India, Mexico, South Korea, and Thailand. The global trend suggests that far from being on any kind of inevitable trajectory, legal protection of women’s bodily autonomy is a result of the choices made by those in power—whether appointed judges, elected politicians, or a combination of the two.

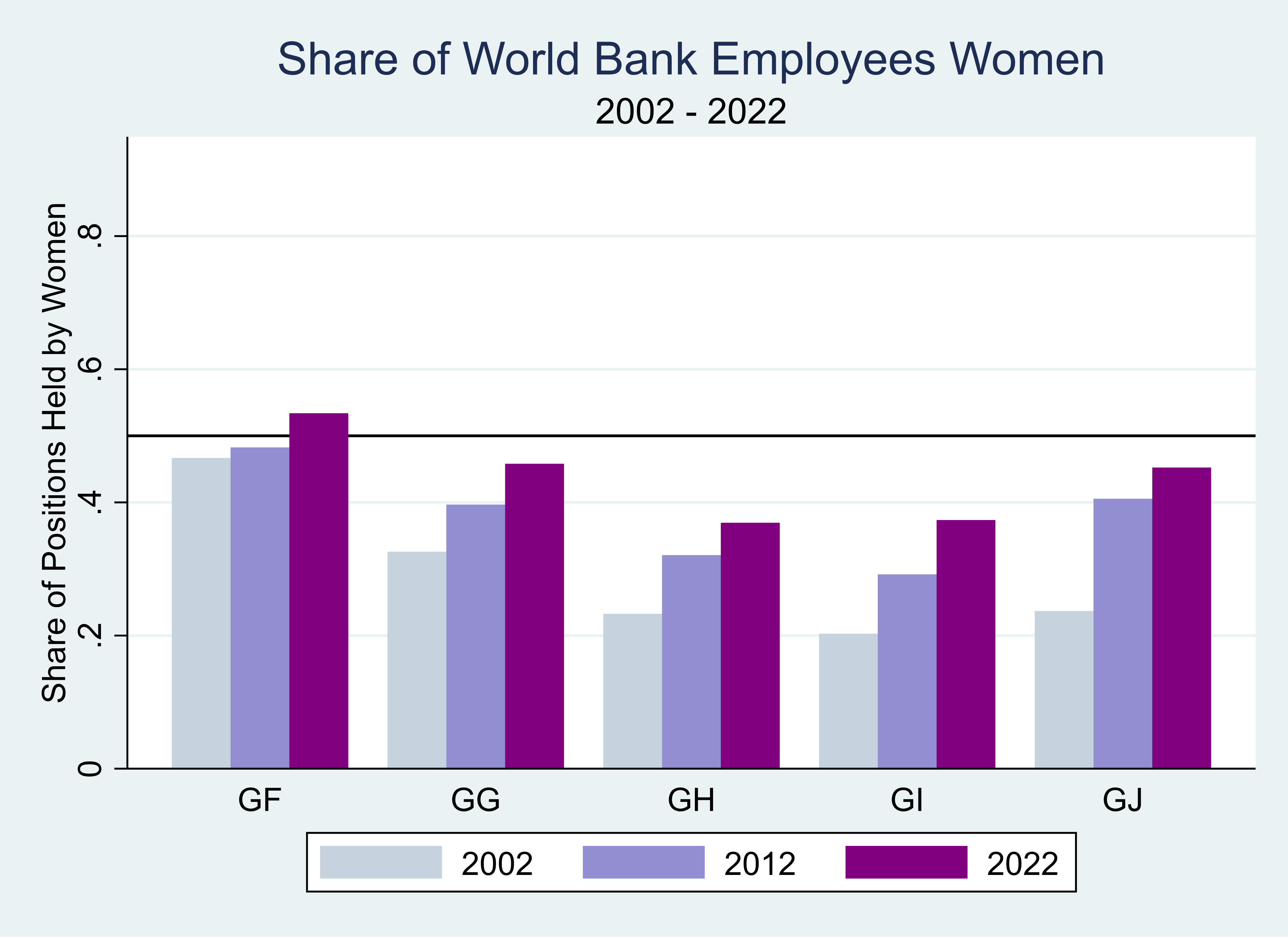

Second, changing the profile of those in power makes a difference to the rights and protections they choose to uphold or strike down: globally, there is a correlation between parliamentary seats held by women and liberalization of abortion laws. This adds to a wider evidence base establishing that when more women are elected to positions of power, the issues women tend to care about are given more attention.

Women currently constitute just 27 percent of the US Congress—which is already record-breaking for the US context, representing a 50 increase from women’s representation in Congress 10 years ago. But this minority still stands in contrast to countries including Rwanda, Cuba, Nicaragua, the UAE, Mexico, New Zealand, Bolivia, Iceland, and Costa Rica, where women make up over 45 percent of national legislatures. The United States has also never had a woman elected to the presidency, in contrast to 38 percent of governments that have had a woman serve as head of government or state.

Based on our review of what has happened around the world, until the United States government gets more women—including and especially women from lower-income communities; racial, ethnic, and religious minorities; and other traditionally marginalized populations—into positions of political leadership, we should not expect drastic improvements in either our domestic or foreign policy approach to promoting gender equality.

The team of us focused on gender equality at CGD has spent the last two years generating and synthesizing evidence on what is needed to promote a more inclusive recovery from the COVID-19 crisis and longer-term gender equality. Our work led us to propose a policy package, framed around increased and improved investments in “cash, care, and data.” But it’s clear that any good policy package will need to be coupled with the presence of political actors receptive to its adoption and implementation. Without a United States government and governments around the world that reflect the perspectives and priorities of their constituents, there’s a huge risk of evidence-based, well-crafted policy recommendations falling on deaf ears.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.