A joint analysis with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows the Trump Administration’s proposed budgets cuts could leave US development spending further behind than ever on its fair share.

The Trump administration’s March budget proposal contained dramatic cuts to foreign aid programs, defending these reductions by implying that the United States is paying more than its “fair share” of such aid. The underlying facts contradict this assertion. The United States currently contributes just 0.18 percent of its economy to developmental aid, compared to an overall average of 0.32 percent among the 29 countries examined by the OECD. This means the US already pays $26 billion a year less than its fair share of development aid, as the term is commonly understood, than other developed nations. Rather than closing at least some of this fair share gap, which is nearly unprecedented in magnitude, the initial Trump budget proposal, as well as the likely full budget the administration is expected to release May 23, would widen it considerably, to the largest gap on record. The United States would become the most deficient ever when it comes to providing its fair share of foreign aid.

The administration’s position on foreign aid

On March 16, the Trump administration laid out some of its budget priorities for the upcoming fiscal year. This initial so-called “skinny budget” cut foreign aid by about 28 percent next year—which would reduce ODA by approximately $9 billion, assuming the 28 percent reduction would apply to all development aid funding. President Trump’s personal introduction to this budget justified this dramatic cut in the following manner:

This [budget] includes deep cuts to foreign aid. It is time to prioritize the security and well-being of Americans, and to ask the rest of the world to step up and pay its fair share.

This language implies that other countries are paying less than their fair share of foreign aid while the United States is paying more than its fair share. The budget did not present any facts to justify this characterization.

What constitutes a “fair share”?

The best and most commonly used source on the amount of foreign or development aid provided by high-income countries is the OECD. It collects information on Official Development Assistance (ODA)—“government aid designed to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries”—provided by 29 countries that are members of its Development Assistance Committee (DAC), which includes most of the world’s major donor countries.

Following international norms advanced by the United Nations and others, the OECD’s main metric of ODA commitment is how much aid a country provides as a percent of its available resources (as measured by its gross national income, which is one way to assess the size of a nation’s economy). The OECD thus assesses a nation’s aid commitment relative to its wealth or ability to make such a commitment.

From this standpoint, the average of all donor countries’ ODA as a share of their economies could be viewed as a reasonable “fair share” measure. This measure does not reflect any negotiated agreement on the “right” level of assistance, nor do we put it forward as the correct level, but it does measure countries’ actual assistance spending in relation to each other, something that President Trump himself seems to be calling for. And by this measure, the United States comes up short.

Specifically, the latest OECD data, for 2016, show that:

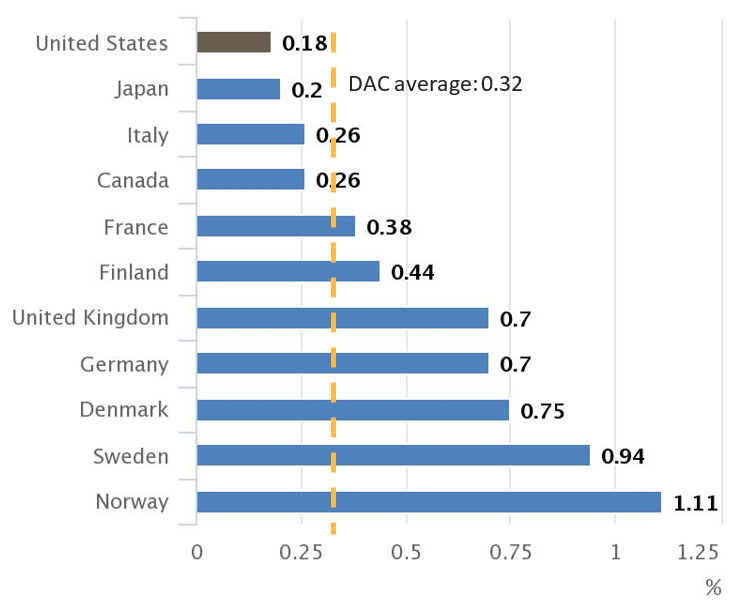

- The US devotes $33.6 billion or 0.18 percent of its economy (using OECD’s gross national income measure) to ODA. In contrast, DAC countries on average devote 0.32 percent (Figure 1). The United States would need to have spent $26 billion more on ODA in 2016 to bring its spending up to 0.32 percent of the US economy. In other words, the United States now contributes $26 billion less than its fair share relative to comparable countries.

- By the OECD measure, US assistance lags that of all the other most highly industrialized countries on the list—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The United States ranks 22nd out of the 29 countries examined in terms of ODA as a percent of gross national income.

- The US is the largest donor in absolute terms, contributing one-third more than Germany (the second-largest). But the US economy is more than five times the size of Germany’s. Thus, Germany contributes 0.7 percent of its economy to ODA, well above the US’s 0.18 percent.

Source: OECD

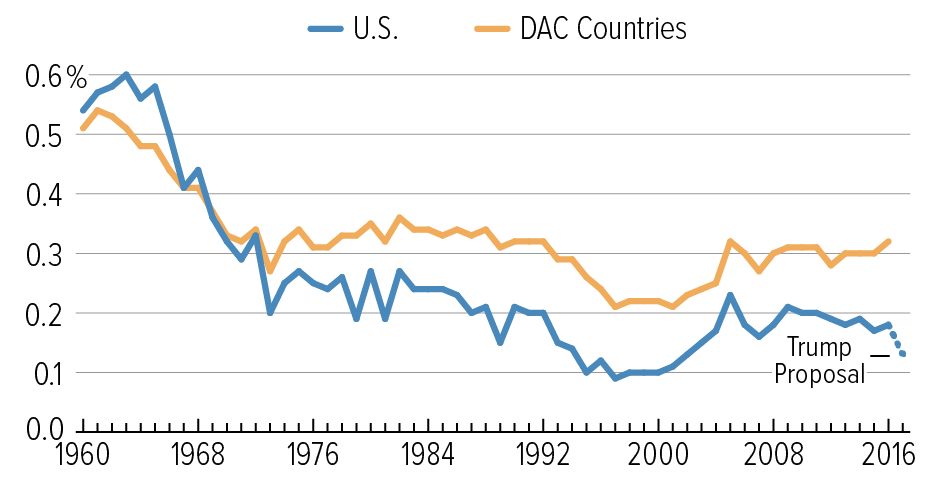

- As Figure 2 indicates, until 1972 the United States contributed its fair share or more of foreign aid. The current gap (0.14 percent of the economy) between US ODA and the DAC average is wider than in all but three years (1989, 1994, and 1995) on record since data collection began 57 years ago.

Spending on ODA as a Percentage of GNI

Note: The Development Assistance Committee (DAC) is an OECD forum for major bilateral providers of development cooperation.

Source: OECD and US Office of Management and Budget. CBPP calculation for Trump proposal.

Proposed cuts on the order of $9 billion would increase the annual fair share gap to roughly $35 billion. When measured as a percent of the economy, the gap between ODA funding from the United States and from all DAC countries would grow to the largest amount on record, with data back to 1960.

US aid would fall further short of need

Despite remarkable gains in poverty reduction globally in recent decades, largely in China, the need for grant-based assistance remains high in Sub-Saharan Africa and in poor countries in other regions. According to the United Nations, 836 million people still live in extreme poverty, with incomes of less than $1.25 a day; 795 million people are undernourished; and nearly 1,000 children die every day due to preventable water- and sanitation-related diseases. The famine threatening the Horn of Africa, with an estimated 20 million people at risk of starvation, dramatically underscores the need for adequate humanitarian relief.

US foreign aid is essential not only because of its humanitarian benefits but also because it addresses the root causes of many conflicts. As 121 retired generals and admirals wrote congressional leaders earlier this year:

The State Department, USAID, Millennium Challenge Corporation, Peace Corps and other development agencies are critical to preventing conflict and reducing the need to put our men and women in uniform in harm’s way. As [current Defense] Secretary James Mattis said while Commander of US Central Command, “If you don’t fully fund the State Department, then I need to buy more ammunition.”The military will lead the fight against terrorism on the battlefield, but it needs strong civilian partners in the battle against the drivers of extremism—lack of opportunity, insecurity, injustice, and hopelessness.

Importantly, this viewpoint reflects an understanding that US foreign assistance dollars are spent effectively overall. While not immune to failures, the body of evidence demonstrates clear, significant successes and an approach to foreign assistance spending that has focused increasingly on program effectiveness and results.

International efforts to target “0.7 percent” of donors’ economies as the correct standard for aid spending has its critics in the development community, and it is not realistic to expect the United States to soon meet this standard, even as leading donor countries like the United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway have. But if President Trump truly wants countries to pay their “fair share,” then the United States has some considerable stepping up to do under a reasonable approximation of this standard. Unfortunately, the president’s budget is a big step in the wrong direction.

Isaac Shapiro is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.