Note (December 4, 2017): The data in this blog present the first release of DRM-coded data in the OECD’s Creditor Reporting Service. Please keep in mind the following caveats. The Addis Tax Initiative—and by extension the OECD data—focus on domestic revenue mobilization; the data don’t capture everything within the broader category of domestic resource mobilization (e.g., strengthening and borrowing from domestic capital markets). Furthermore, because this is a relatively new data classification, the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the data are evolving. There are some known gaps in the data presented below. Bottom line, however, we’re pleased a framework now exists to track US (and other donor) investments in DRM; we hope those reporting data will contribute to quality improvements going forward.

Domestic revenue mobilization (DRM) seems set to be a priority area for the US Agency for International Development (USAID) under Administrator Mark Green. In line with emerging international and domestic consensus on the importance of DRM, Administrator Green has repeatedly highlighted the importance of helping countries mobilize their own domestic resources. Furthermore, DRM, which aims to help partner countries better self-finance their own development priorities, is a promising tool for helping select middle-income countries transition away from USAID’s grant-based assistance, another stated priority for Administrator Green (stay tuned for forthcoming research on transition from Sarah Rose and Erin Collinson).

DRM, which supports strengthened tax policy and administration, is not a new objective for US foreign assistance. For many years, USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and the Treasury Department’s Office of Technical Assistance (OTA) have been working with countries to improve tax collection, customs capacity, public financial management, and the like.

The challenge has been in tracking US (and other donors’) support for DRM activities. Historically, there has been very little data on the amount of assistance going to DRM, but this is starting to change. The 2015 Addis Tax Initiative (ATI) provided the first framework to track donors’ support for DRM activities in a systematic manner through the OECD’s Creditor Reporting Service. ATI used this data in its first Monitoring Report, released in July. While the data only covers projects in 2015 so far, it contributes to a better understanding of what US aid agencies are doing in the DRM space and where they are working. If the United States is looking to step up assistance in this area, it will be instructive to understand the landscape of current efforts.

The United States is the second-largest donor to DRM

The United States is the second-largest donor to DRM, behind the United Kingdom. Other major donors include Germany, the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), and Norway.

USAID leads US DRM efforts

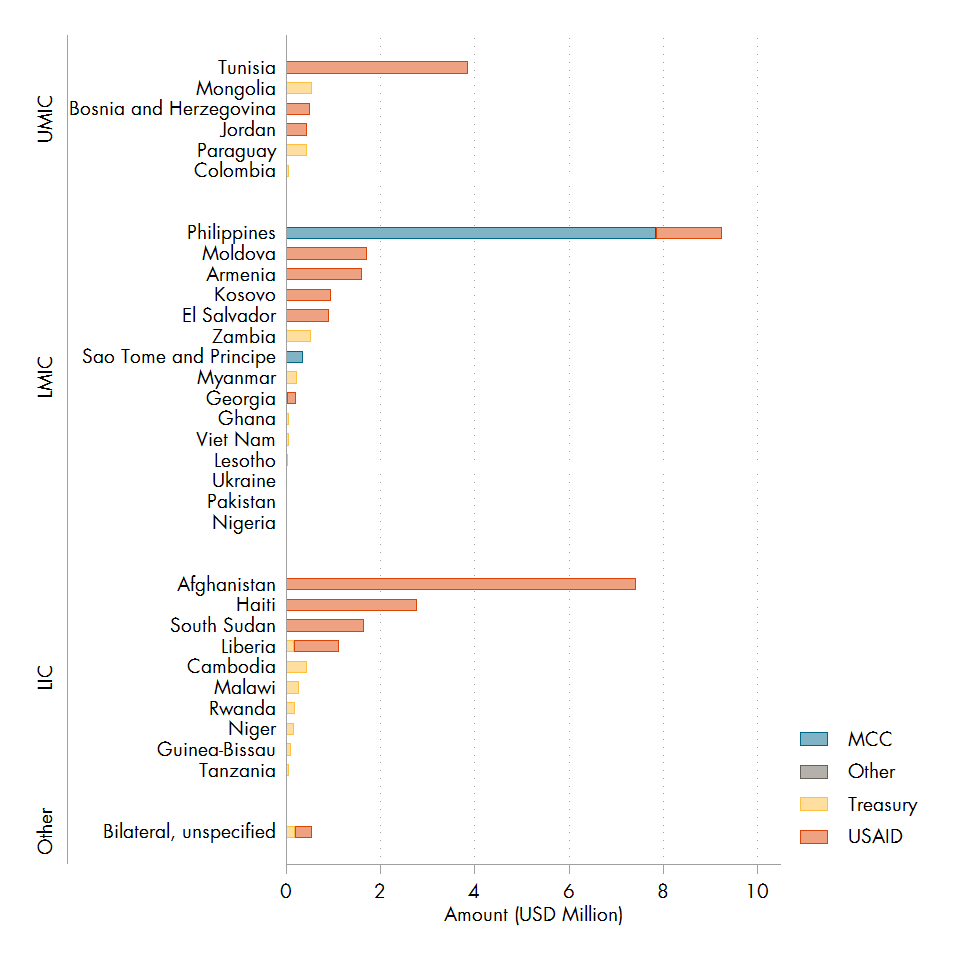

In 2015, the United States delivered $37 million in DRM-focused assistance in 32 countries. USAID contributed the most, disbursing nearly $25 million, followed by MCC ($8.2 million), Treasury ($3.7 million), and the US Trade and Development Agency (a single $8,000 feasibility study in Pakistan).

The type of engagement varies by agency. MCC funded comparatively larger projects, with an average project size of $2.1 million across four projects. On the other end of the spectrum, the average size of the 40 Treasury projects was around $9,000. USAID’s 37 projects had an average cost of $671,000.

The majority of US assistance to DRM (66 percent) is delivered as project-type interventions—for example, training officials, modernizing IT and other equipment, supporting public awareness campaigns and taxpayer outreach, and modernizing tax collection infrastructure. Another 27 percent of DRM funds support US advisors to deliver in-country technical assistance (mostly through Treasury). Additionally, USAID contributed a small fraction (under $1 million) of assistance to multilateral institutions.

The Philippines and Afghanistan are top recipients of US DRM assistance

The United States provided DRM assistance to 32 countries in 2015. Of the total US spending on DRM that year, 40 percent went to low-income countries, 44 percent to lower-middle-income countries, and 6 percent to upper-middle-income countries—which broadly tracks the distribution of the US government’s overall development aid allocation by income category.

Consistent with the models of each agency, the MCC is the most focused of the agencies. In 2015, MCC’s DRM projects were limited to only two countries, with one, the Philippines, dominating. By contrast, the work led by USAID and OTA was dispersed more widely. USAID worked in 14 countries, spending an average of $1.8 million per country. Treasury worked in 19 countries, spending an average of only $197,000 per country.

Recipients of US aid to DRM, 2015

Considerations for expanding US contributions to DRM

As the United States seeks to refine and possibly ramp up its approach to DRM, this analysis points to several considerations that US foreign assistance agencies should think through:

-

What is the role of US aid agencies vis-à-vis other donors? The United States is a significant donor to DRM efforts—but it’s not the largest. Given the substantial efforts of many other bilateral and multilateral donors—including the IMF’s Tax Policy and Administration Topical Trust Fund and the OECD’s Tax Inspectors Without Borders—the United States should a) identify how best to support multilateral efforts, and b) establish its comparative advantage in this area vis-à-vis other actors in the space.

-

How can US agencies better coordinate DRM efforts to maximize effect? Each of the three agencies contributing to DRM efforts has its own approach. MCC funds substantial partner country-identified interventions in a small number of countries. OTA sends financial advisors to work in partner country governments on revenue policy and administration and/or budget and financial accountability. USAID covers a wide array of goals and instruments, generally focused on strengthening revenue administration, assisting on tax reform, and encouraging a culture of tax compliance, and often covers a wide range of smaller interventions. The agencies do coordinate with one another; both MCC and USAID fund OTA’s work, for example. Continued focus on coordination will remain necessary to maximize effectiveness.

Where should the United States focus increased assistance? US agencies operate DRM projects in a range of countries, from upper-middle-income countries like Tunisia to fragile, low-income countries like South Sudan. For countries at the higher-income end of the spectrum, DRM could be particularly useful as part of a strategy to transition partners away from traditional, grant-based foreign assistance by building their capacity to self-finance their development objectives. For small, fragile states, DRM assistance can lay the groundwork for other reforms, like state-building. In all cases, DRM efforts must be undertaken with due attention to the risks of overburdening poor people. A study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo found that the real tax rate on low-income Congolese is 40 percent of their wealth. And CGD non-resident fellow Nora Lustig found that the extreme poverty headcount ratio may actually be higher after taxes and transfers in some countries than before.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.