In New York, on Valentine’s Day, 450 tax professionals will gather for a major conference on tax and development. The Platform for Collaboration on Tax, a joint effort of the IMF, OECD, World Bank, and the UN, will bring together finance ministers and senior tax officials, development agencies, foundations, International NGO leaders, academics, researchers, and tax professionals from the private sector, around the role of tax in advancing progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

This gathering—perhaps the largest and most diverse of forum on tax and development—reflects the increasing attention on tax for development, and the critical role that international civil society have played in pushing it up the agenda. It is clear that countries’ own resources are fundamental to development, providing the largest share of financing, even in the poorest countries. There is both potential and need for governments to collect more tax and to do it more effectively, as economies grow. To support this, the Addis Tax Initiative was launched in 2015: 19 donor countries, plus the European Commission pledged to collectively double their technical cooperation for domestic revenue mobilisation by 2020. Partner countries—including Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Philippines, and Uganda—pledged to step up domestic revenue mobilisation. And all players committed to promoting “Policy Coherence for Development.” Around the same time the G20/OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting programme launched into action, and now involves 111 countries, including many emerging and developing economies.

But discussion on tax and development can be pretty incoherent, both within and between different sectors. Debates between those seeking to invest and grow businesses and to improve investment environments, and those seeking to secure public revenues and accountability through domestic resource mobilisation have often been fractious, disconnected or antagonistic. A symptom of this is the tendency for inflated expectations about the scale of revenues at stake in relation to multinational corporations and misunderstandings and contested definitions on the issue of illicit financial flows.

Towards policy coherence

My new CGD paper seeks to get beyond the debates and misunderstandings about the “big numbers” to explore what real policy coherence for development over tax could mean. It highlights underexplored opportunities for improving domestic resource mobilisation if we “do tax differently” thinking of taxpayers not only as sources of incremental revenue but also as players in the economy, and stakeholders for state capability (see Eight Ideas).

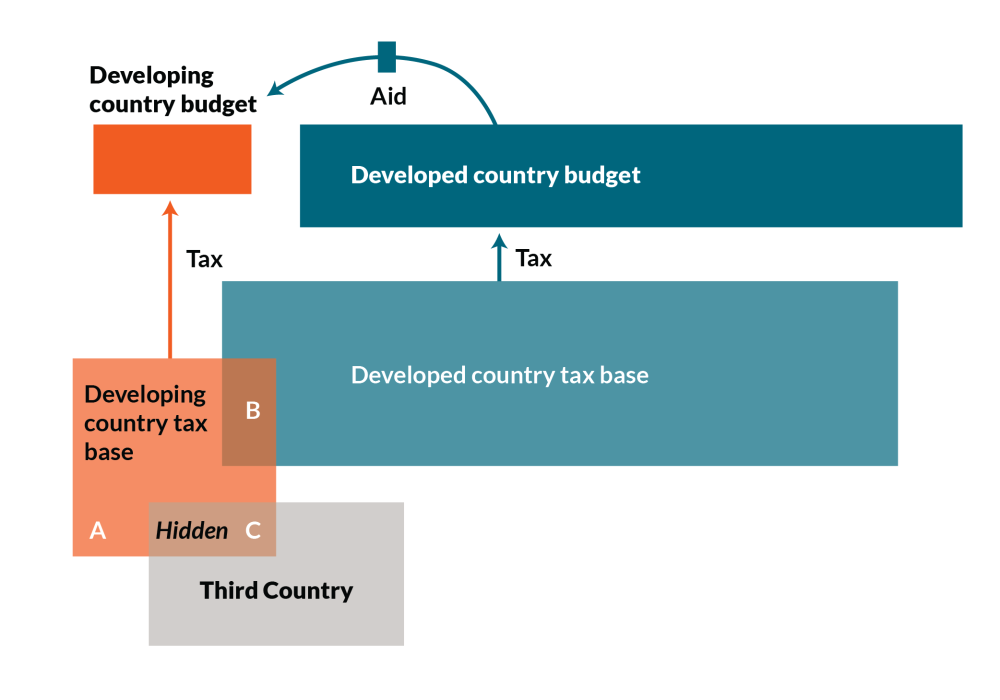

Getting a sense of relative proportion about international and domestic tax issues is a critical starting point. It is often suggested by both international actors and domestic politicians that international tax issues are the most important factor holding back domestic resource mobilisation. The paper looks at broad estimates of potential additional tax in the three areas, illustrated below: (A) the domestic tax base, (B) the “overlapping tax base” between countries (such as where taxes on the profits of multinational corporations are determined using transfer pricing and tax treaties) and (C) the “hidden tax base,” where high net worth individuals use opaque offshore structures to evade taxation.

It finds that while estimates of the potential gain from improving international tax rules and administration across B and C could approach 1 percent of GDP for low and lower middle-income countries, potential additional tax from domestic policies across the broad tax base could be around 9 percent of GDP. As Mick Moore and Wilson Prichard at the International Centre for Tax and Development outline, there are significant opportunities to collect more tax as the economies of low-income countries grow, mainly through domestic policy action areas such as reviewing tax expenditures and incentives, improving VAT systems, collecting personal income taxes, property taxes, and enhancing the design of extractive sector fiscal systems. Many potential gains are achievable over time with modest financial expenditure and accessible levels of technical expertise, although care also needs to be taken that taxes do not increase poverty. The main enabler of change is political commitment strong enough to overcome vested interests among taxpayers, politicians, and tax administrators themselves. Ultimately the development benefit depends on taxes being spent well to provide valued public services.

This leaves donor countries, international organisations, foundation funders, and international NGOs with a dilemma: many of the most internationally accessible and salient levers of policy and influence relate to the 1 percent of cross-border rules rather than the other 9 percent of domestic tax policy and spending. Technical advice and capacity building in areas such as property tax and reducing tax exemptions can be “pushing on a string” if there is no political will to tax local elites more, or to give up the direct political tool of discretionary tax exemptions. There is a real danger that an intense public focus on the accessible and morally appealing (and often inflated) prospect of collecting incremental tax revenues through international tax action will distract government and civil society from a clear focus on how tax revenues, overall are collected and spent, and undermine investment. It can already be seen, particularly in the extractive industries, that inflated expectations can lead to vicious circles of policy and administration uncertainty and mistrust between taxpayers and governments, and to fiscal indiscipline and economic underperformance.

Fundamentally, what should prick the bubble of inflated expectations is remembering that for any government to collect a large proportion of its country’s GDP as tax revenue, it requires a large proportion of people in the economy to bear the burden of tax. The ability to use international mechanisms (or the push of technical advice) to compel people to pay more tax than has been secured through a social contract with their government is (thankfully) limited.

This is not just an inconvenient truth about the limits of development cooperation, but a fundamental one about the process of development. National development involves a shift from being a low productivity, low-tax country where voters do not expect fair treatment from revenue authorities or decent services from government, to being a prosperous country where public goods are secured by a government held accountable for tax and spending. It requires sustained economic growth and development of accountable institutions. And it is something that is done by people, not to people.

A path forward on taxation and development

This recognition that “tax is political” tends not to come up so much in the technically focused session of international tax conferences—focused on global tax rules, cooperation mechanisms, and capacity building programmes—but does in the late-night conversations.

Policymakers, tax experts, tax payers, tax professionals, and advocacy organisations need to find new ways to test ideas, share knowledge, collaborate, and learn together. This requires new narrative about tax and development, which is not defined by the promise of unfeasibly large revenues from taxing a narrow tax base multinationals, or solely focused on the incremental adoption of “best practice” tax policy and administration. Keeping the triple goals of revenue mobilisation, sustained economic growth and development of accountable institutions front and centre may provide a route towards common ground.

One useful way to think about the politics of taxation in practice, is in terms of the shift “from deals to rules” as described by Lant Prichett, Kunal Sen, and Eric Werker. They view development as a linked process through which fair and enforced rules co-evolve with increasingly productive economies. The linkage is that most efficient firms tend to do better in investment environments where more of the transfers to and from the business (including taxation) are through official, predictable “rules” based channels, whereas less efficient ones can out-compete them where rents can be informally negotiated through “deals.” Taxation is essentially a rules-based form of extraction. What international businesses say they hate about tax is not so much the prospect of paying it, but facing uncertainty about it.

Prichett, Sen, and Werker argue that we should stop thinking of the private sector as a homogenous group, but look instead at the microclimates for different kinds of firms, based on the relationship between local elites and international market players, and how these can give rise to constituencies for reform. This opens up opportunities to think about how internationally accessible policy and influence levers might support the political economy of efficient, rule-based business in key sectors, leveraging the interest of taxpayers as advocates and supporters of reform.

While there is certainly need for long-term thinking on global tax reform and potential redesign of the tax system, as well as immediate action to close loopholes in the international tax system, and build capacity within revenue authorities, it is worth exploring the potential to develop targeted and practical approaches which view taxpayers not simply as potential sources of additional revenue, but as potential constituencies for reform in a shift from deals to rules.

Eight ideas

The paper raises eight ideas for win-win approaches:

-

An “MLI for Development.” The Multilateral Instrument (MLI) has shown how tax treaties can be changed multilaterally. Could an MLI for Development be developed based on a set of minimum treaty provisions to support the needs of developing countries to balance investment certainty and simple revenue collection?

-

Peer review mechanism for responsible tax practice. Multinational corporations are increasingly publishing tax principles and policies. Could businesses and others develop a peer review or broader assurance process on their practice and performance as responsible tax payers?

-

Dispute resolution for development. Dispute resolution and mandatory arbitration are being promoted as part of the BEPS Action Plan as a means of securing tax certainty. What steps should be taken to make dispute resolution mechanisms accessible and useful for low-income countries?

-

Improving the effectiveness of the UN Tax Committee. The UN Tax Committee plays an important role as a forum for developed and developing countries to address tax issues, in complement to the OECD processes, but it is constrained by lack of resources and some of its own procedures. How should the UN Tax Committee evolve to make it a more effective forum to serve the needs of developing countries?

-

Business tax roadmaps. The Global Platform is promoting Medium Term Revenue Strategies as a coordination mechanism for policy, administration and legal development. Beyond being a bureaucratic mechanism linked to international funding, could governments engage with business stakeholders and develop business tax roadmaps to certainty to enable long-term investments?

-

Technology solutions for identity assurance. The ability to identify the ultimate beneficial owners of accounts and corporations is crucial to detecting, tracking, and preventing illicit financial flows, and for tax administration, but, it does not necessarily follow that all ownership details should be required to be publicly searchable. Could a blockchain or other technology solution be used to provide a solution for compliant confidentiality, and secure identity and beneficial ownership certification?

-

Investment grade tax policy for project finance. Tax uncertainty is a key barrier in developing multi-country investments such as power and infrastructure projects with bespoke deals often negotiated to overcome underlying complexity in the tax system. Could a simplified system for taxation of project finance be developed through a multisector collaboration involving governments, private sector, and development finance institutions?

-

A “race to the top” of international financial centres. International Financial Centres are decried as ‘tax havens’, but at the same time they provide useful access to internationally trusted legal systems and modern, simple administration. Can the characteristics of a responsibly competitive international financial centre be identified, measured and developed into an index of responsible competitiveness of financial centres demonstrating integrity and ability to mediate and support investment?

I will continue to point out misunderstandings and inflated expectations around the tax “big numbers,” if they continue to be produced. The aim is not to turn people away from focusing on the international aspects of tax and development but to see if we can find a common ground to explore and test ideas which could gain the support of policymakers, taxpayers, civil society, international organisations, and tax professionals.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.