In a recent SNL sketch Bill Haider is a white celebrity filming a commercial in a village using black people as props to plead for “39 cents a day” which he claims is “all these people need to survive.” Unfortunately these props start talking back, telling him to “ask for more” and challenging him on how he figures that 39 cents is enough. One woman says “How are you going to save us with just 39 cents, I am trying to do the math in my head and I just can’t see it.” The increasingly frustrated celebrity first tells them this number has been calculated by “educated and caring people” and it is all they need and then admits that for PR purposes it just has to be “for the price of a cup of coffee”—to which another villager asks: “Why not the price of an Arizona Tea? They are 99 cents!”

As it so often does, satire captures quickly and perfectly a grand tension, one that is playing out over the definition of the post-2015 development agenda.

The existing MDGs were a brilliant public relations ploy to create a viable political coalition in the rich Western countries to support development finance in the aftermath of the end of the Cold War, a time when many feared Western governments’ support for development would wane. The pitch was to “define development down” (Kenny and Pritchett 2013) to a set of concrete goals that were narrow enough and penurious enough to make a simple compelling message (“eradicate extreme poverty”) across a broad enough agenda to keep powerful constituencies at the development table (e.g. goals on education, gender, HIV/AIDS, environment). Whether the MDGs have been a success in promoting their objectives is an open question—and will almost certainly remain so as the question is not whether there has been progress on the indicators (there has) but whether this progress was due to the MDGs. One thing that is sure is that net Official Development Assistance (ODA) was US$51 billion in 2000 and US$132 in 2012.

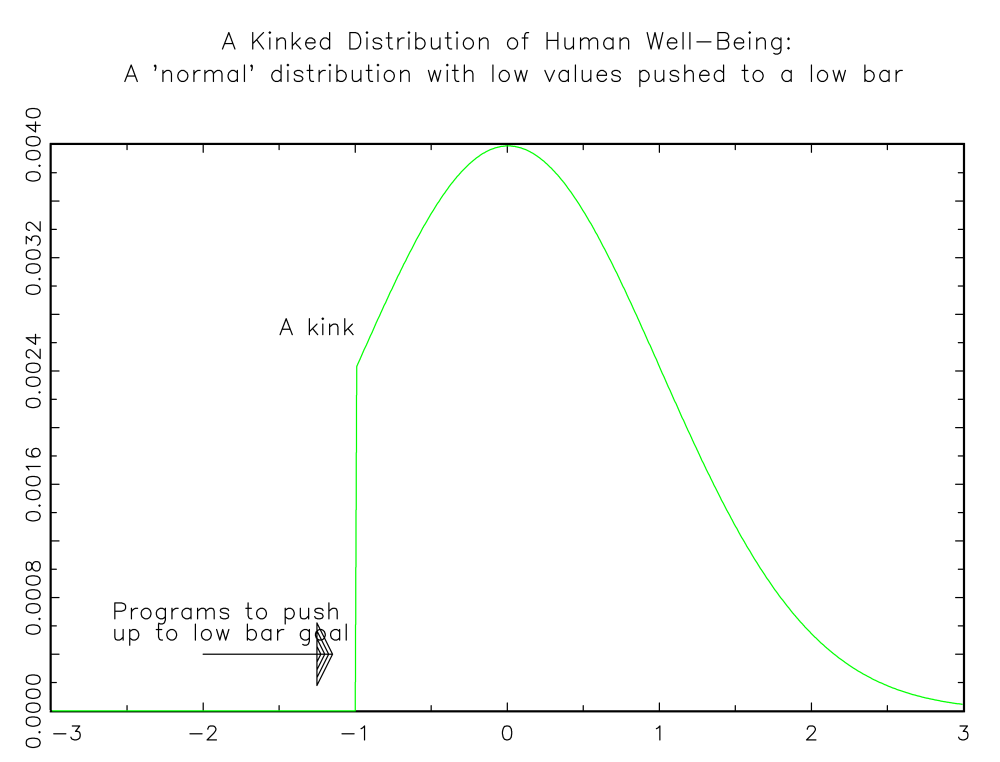

But, as I argue in my recent Kapuscinski Lecture the cost of the MDGs was a re-framing of nation’s ambitious development agendas into a “kinky” approach to development. I call this approach “kinky” because by setting in each of the domains of the MDGs a very low bar goal (e.g. “extreme poverty”, “primary school completion”, “access to safe drinking and basic sanitation”) this implies that the aim of development is not a broad and shared overall improvement well-being of everyone, but rather just pushing people below the low bar up to that threshold. This would mean the MDGs could be fulfilled with a “kink” in the distribution of well-being at the low-bar goal (see the figure).

In the framing of the new post-2015 development agenda the developing countries have pushed back against the kinky approach to development, for several good reasons.

First, in reality there is no line across which there are dramatic changes in well-being. Less is worse and more is better—but without any sharp thresholds (the obvious exception is health). A child who completes primary schooling is better equipped than one who completes one year less than primary and one who completes primary plus one more year better equipped still. Nothing special happens at the threshold. When household income goes from just under the dollar a day threshold to just over—nothing special happens. Households are better off when water is safer, closer, and more reliable—there is no special threshold of “access.”

Second, developing countries and their citizens have legitimate aspirations to reduce global inequality and converge on the levels of well-being of the rich industrial countries in all domains. Why should any developing country adopt a goal that the USA or Denmark or Japan wouldn’t? Why primary schooling when every developed country shoots for universal secondary? Why just a few diseases when every developed country shoots for universal health care access? Why “dollar a day” when developed country poverty lines are ten times higher?

Third, as more and more developing countries are electoral democracies the demands to improve the lives of the entire population—including at least the broad middle—are increased. No democratic country can adopt an exclusionary development vision that benefits only the few—either cronyism at the top or kinkiness at the bottom. The “median is the message” (Birdsall and Meyer 2014) has to be true not just of economic progress but across the board.

With the emergence of the “developing” countries—especially the giants of China and India but also Indonesia and others—into “middle income” status there is less concern among developing countries with concessional finance (and less acquiescence with low bar as a PR tool to generate finance) and more concern for re-framing development back to broad aspirations and inspirational goals.

The current draft of the post-2015 development will mark the end of the brief era of kinky development and a return to a broad and ambitious agenda framed more by the aspirations of people from developing countries and less by what appeals to rich country voters. This will be difficult because a clearer separation will need to be made between a broad and ambitious definition of global development and the priorities for allocation of concessional finance, with the latter becoming increasingly less important.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.