Despite the continuing controversy over India’s Unique Identification Program, also known as Aadhaar, it is making remarkable strides. With more than 500 million people now enrolled, the program will soon pass its midway point. But enrolment isn’t uniform throughout the country. The smaller and richer states have generally made the most progress while poorer states are generally lagging behind. That may be as you would expect, but if it is hoped that UID will improve the administration of social programs and transfers, getting it done well and quickly is arguably even more important in poor states than in rich.

In this blog, we explore why some regions are lagging behind others and look to India’s a rural health insurance scheme Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) as a useful comparator. But first, the numbers.

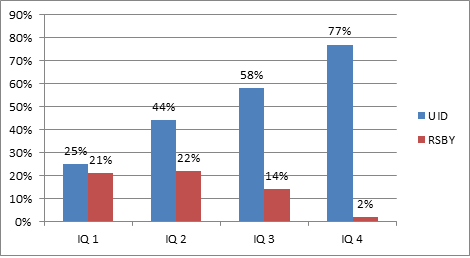

Figure 1: UID and RSBY coverage rates By States, 2013 (not weighted for population size)

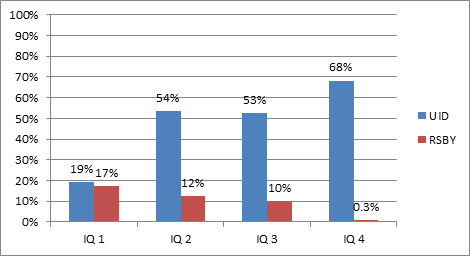

Figure 2: UID and RSBY coverage rates By States, 2013 (weighted for population size)

Figures 1 and 2 show average UID and RSBY enrolment rates for states by income quartile, unweighted and weighted by state population. The states with the highest UID coverage were Delhi (95%), Goa (91%), Sikkim (89%), Andhra Pradesh (89%), and Pondicherry (88%). With the notable exception of Andhra Pradesh, all are in the top income quartile. Coverage is also high in some other poor states such as Jharkhand (71%) and Tripura (84%). For the richer states, the percentages may be inflated by the registration of migrants who are not included in the population estimates, but nonetheless eight states have exceeded 80% coverage, which can be considered a reasonable threshold to apply an ID system to a range of uses.

Most states with the lowest coverage, such as Assam (0.2%), Mizoram (0.9%), Bihar (4.4%) Jammu and Kashmir (6.6%), and Chattisgarh (7.3%) are poor. Much of the difference in coverage may be due to differences in infrastructure and capacity, but politics may also be affecting the rollout pattern. Jharkand, for example, has appealed to make Aadhaar mandatory, despite a Supreme Court order to the contrary, and is also piloting a scheme to link payments under NREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) to possession of the Aadhaar number. On the other hand, states such as West Bengal and Tamil Nadu have been less supportive, with chief ministers writing to PM Manmohan Singh in opposition to the linkage of cooking gas subsidies to Aadhar numbers .

Incentives to enroll may also be a factor. UID’s rollout pattern is very different from that of India’s other large-scale biometric program, the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY), a rural health insurance scheme that exists in many states at the district level. RSBY coverage is highest in the poorest states. Only families that are below the poverty line are eligible, and in some cases RSBY enrolment exceeds 50% of the number of qualifying families. In addition, states with higher incomes often have their own health-care insurance schemes, such as Tamil Nadu’s Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme which may provide competition to RSBY. The RSBY example suggests that if getting an Aadhaar number were linked to programs and services that Indian citizens are demanding, the enrolment gaps could be closed quite rapidly.

It remains to be seen how this plays out, given the reiteration by the Supreme Court that enrolment in UID is voluntary. There is evidence that people will sign up for an enhanced ID if it improves their ease of access to valued services. The Global Entry program, which allows prescreened members speedy access to re-enter the United States and avoid long lines appears to be working despite its $100 price tag; over 1.5 million people have signed up for it so far. In the end this will be the test for Aadhaar, the extent to which it is able to improve the quality and efficiency of the delivery of services.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.