In 2015, there were 77,470,857 visits to the United States from other countries. These visitors brought tremendous benefit: not only did they each spend an average of $4,400 on US goods and services during their stay, but also they helped US firms engage with foreign markets, raise the quality of students here, and help with the diffusion of knowledge. We should want more of these tourists and businesspeople, and the above suggests a real cost to inaccurate visa screening mechanisms—of which blanket bans are a prime example.

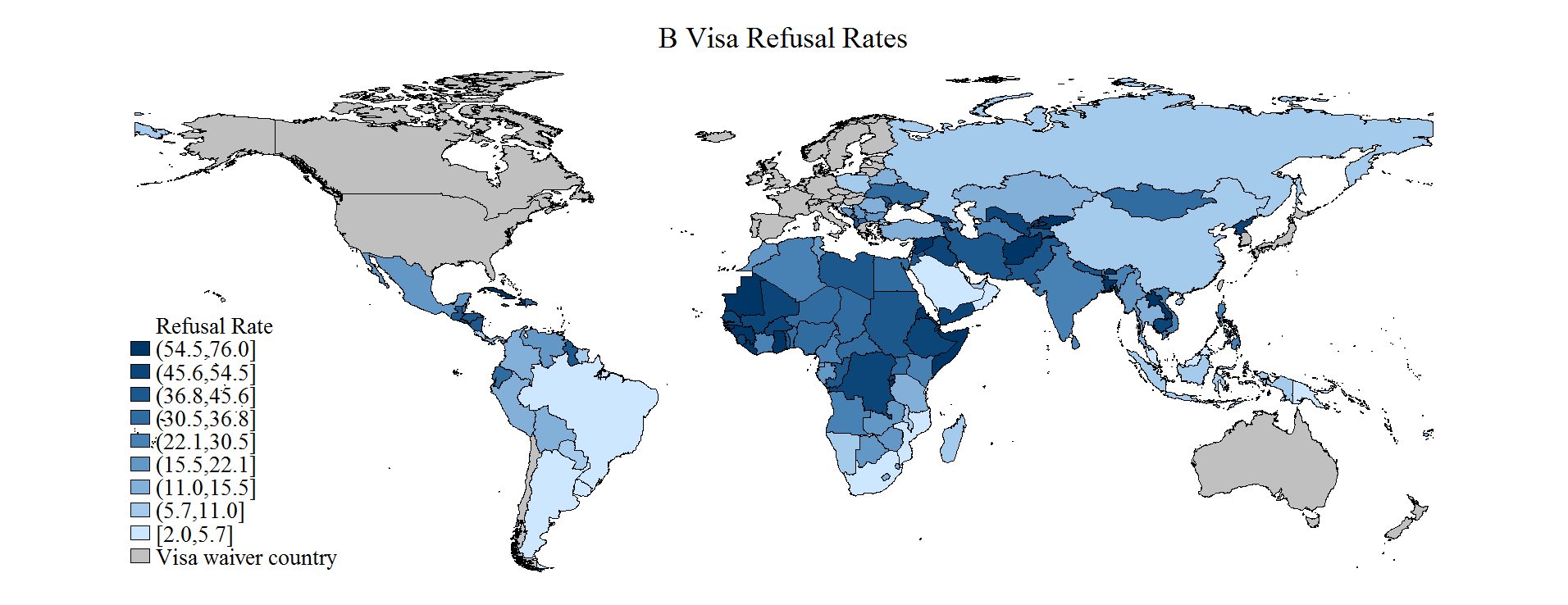

Many of the common source countries for visitors to the US are covered by a visa waiver program which means most citizens wishing to temporarily visit for work or vacation don’t have to apply for a visa before traveling. But for the rest, entering the US requires applying for a visa at a US consulate and attending an interview before they set foot on a plane. In 2016, over 8.5 million people from 196 countries applied for a tourist or business (B class) visa to visit the United States. Unfortunately, many potential visitors that needed a B-visa before their journey were out of luck: one in five of their applications was rejected. In some countries, the figure was far higher: if you are Ghanaian, for instance, there’s a 63 percent chance your application will be denied.

Why are they rejected?

The official guidance offers insight:

An application may be denied because the consular officer does not have all of the information required to determine if the applicant is eligible to receive a visa, because the applicant does not qualify for the visa category for which he or she applied, or because the information reviewed indicates the applicant falls within the scope of one of the inadmissibility or ineligibility grounds of the law. An applicant’s current and/or past actions, such as drug or criminal activities, as examples, may make the applicant ineligible for a visa.

And, in particular, under INA Section 214(b), you will be denied a visa if you “did not overcome the presumption of immigrant intent, required by law, by sufficiently demonstrating that you have strong ties to your home country that will compel you to leave the United States at the end of your temporary stay.” In other words, the US assumes you will use your temporary visa as a way to migrate permanently unless you prove otherwise.

Deterrent effect plus refusal risk equals…

The complex process and the risk of rejection will deter potential visitors from applying in the first place: in many countries, a $160 application fee (plus the hassle of the application and interview) enters you into a process where you’ve got less than a 50:50 chance of getting a visa. And then the rejection rate will further lower the number of applicants who actually get visas to travel. This double effect greatly reduces the number of visitors to the US.

The relationship between the visa refusal rate and the number of visas granted is large, significant, and negative. Simple OLS regressions suggest that, controlling for GDP, population, and country fixed effects, a 10 percentage point increase in the refusal rate is associated with a 10 percent decrease in the total number of visas granted.

The exact magnitude of the total deterrent effect of visa requirement plus refusal risk is uncertain—international estimates for the deterrent effect of visas range from a 20 percent decline in visitors in recent panel analysis to 70 percent in earlier cross-sectional literature, while an analysis of the visa waiver program suggests travelers from countries participating in the program were 7 to 9 percent more likely to visit the United States than travelers from countries not in the program. But let’s say the total burden of a visa requirement and refusal risk reduced the number of applicants from B-visa countries by 30 percent. Moving to a visa waiver program for all of those countries would increase the number of visitors to the US from those countries from 8.5 million to over 11 million, bringing in an estimated $14 billion dollars—equal to the entire state budget of North Dakota and larger than the budget of 16 other states.

Doubtless many of the visa rejections are valid—reflecting overstay or other risks—but this considerable economic hit does suggest there could be significant advantages to improving screening accuracy so that it produces as few false positives as possible. If we reject someone, we better be sure we have a good reason. And—from an economic perspective—it suggests blanket bans such as the ones re-proposed in Monday’s Trump Administration Executive Order are a big step in the wrong direction.

Data on refusal and approval rates used in this analysis are public records from the US State Department. For replication ease, the data and Stata code to produce the graphs and regressions can be found here. The shapefiles to create the map were downloaded from GADM.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.