The education gaps that are closing between boys and girls in many countries persist in Pakistan. Pakistan has among the most out-of-school children in the world (23 million), and one of the biggest gaps between boys and girls, measured both by enrolment and learning. For every 100 boys enrolled in school in Pakistan, 86 girls are enrolled, and girls are less likely than boys to be able to read and do simple maths.

An important driver of gender gaps are gender norms. In Pakistan, men are generally expected to be breadwinners and women are generally expected to stay home. This leads to higher demand for school for sons than for daughters. Depressingly, demand for school for girls may come more from improving their marriage prospects than their job prospects.

Our large new household survey on the factors associated with differences in gender norms sheds light on what policymakers can do in the post-COVID world to address the gender gap and improve opportunities for girls (the survey dataset is available here). Here are four things we learnt from the survey results.

Lesson 1: A large minority of men think women should not be allowed to work outside the house

Gender norms are still regressive in Pakistani society. Forty percent of women need permission from a family member to seek or remain in paid employment, according to the 2019 Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) survey. Less than 10 percent of households say women can decide for themselves.

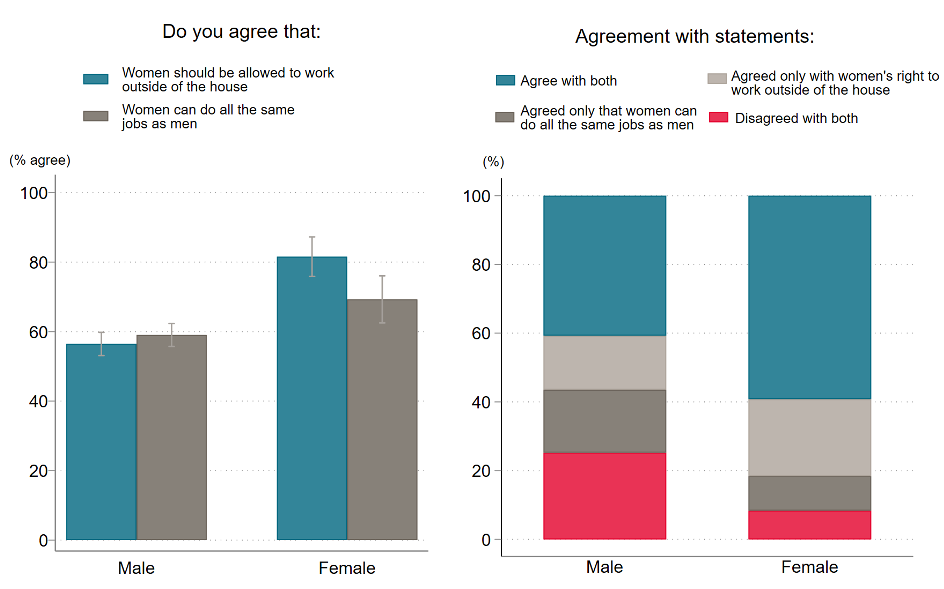

Behind the power dynamics are powerful gender norms. In our sample, 43 percent of men think women should not work outside of the house. Just under half think women cannot do the same jobs as a man.

On the other hand, women are much more likely than men to think that they should be allowed to work. Over 80 percent think they should be allowed to work, and 69 percent think women can do all of the same jobs as men (Figure 1a).

Figure 1a. Gender roles and biases on female participation in the labour market

Note: data collected in February 2021. Sample size of 852 male respondents and 179 female respondents. Vertical bars indicate 95 percent confidence intervals. T-tests show the difference between the proportion of females agreeing with each statement is statistically significant.

Women in Pakistan also face other barriers related to gender norms when entering the labour market, such as lack of access to safe transportation, lack of female facilities in the workplace, and time constraints due to household responsibility. Of women who are not actively seeking paid work, 92 percent said they would be interested in working. Over 70 percent are not seeking work either because their husband or father won't let them, or because of their household duties (2019 PSLM).

Although half of men think women should be allowed to work, almost a third of these (28 percent) don’t think a woman can do the same job as men. This raises concerns for women who are already in the labour market, as they have fewer and less diverse job options. These are concentrated in low-pay sectors, sometimes even when women have completed secondary education.

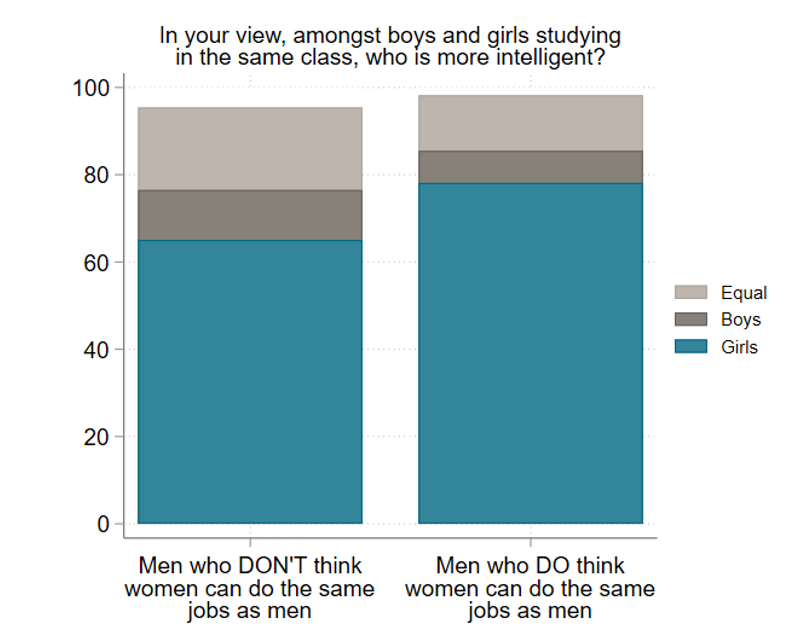

What is puzzling is that most respondents in our sample believe that girls are more intelligent than boys in a classroom (Figure 1b). This is true even among the majority of men who don't believe women can execute the same jobs as men (65 percent), possibly highlighting that women’s acceptance into the labour market is related more to social norms and biases than to perceptions of their capabilities.

Figure 1b. Majority of men think girls are more intelligent than boys in the classroom

(By men’s belief that women can do all the same jobs as men)

Note: sample size of 852 men

Lesson 2: Pakistani men and women overestimate their peers’ disapproval of women working outside the home from others

One potential avenue for improving gender equality is through addressing "misperceived norms." For example, in Saudi Arabia, the majority of young married men privately think that women should be allowed to work, but also think that other men disapprove of women working. Correcting this misperception, by revealing that the majority of others actually also approve, led some married men to help their wives search for and find jobs.

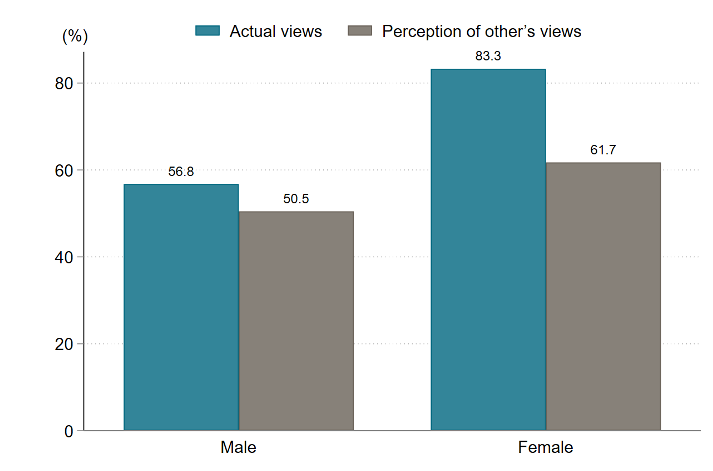

We replicated these findings on misperceived norms in our sample. We asked respondents “how many [men/women] out of 100, [they] believed agreed with the statement that a woman should work outside the home.”

Men in our sample do overestimate disapproval by other men, by around 5 percentage points. Interestingly however, women overestimate disapproval by other women by much more—by over 20 percentage points.

There is clear room to correct misperceptions of acceptance for women to work outside the household in Pakistan.

Figure 2. Both men and women overestimate disapproval of women working outside the home from others

Note: to capture perception of other's views we asked respondents "We asked 100 [men/women] like you the same question. How many do you think agreed that a woman should be allowed to work outside the home?"

Lesson 3: Schooling is associated with positive gender attitudes

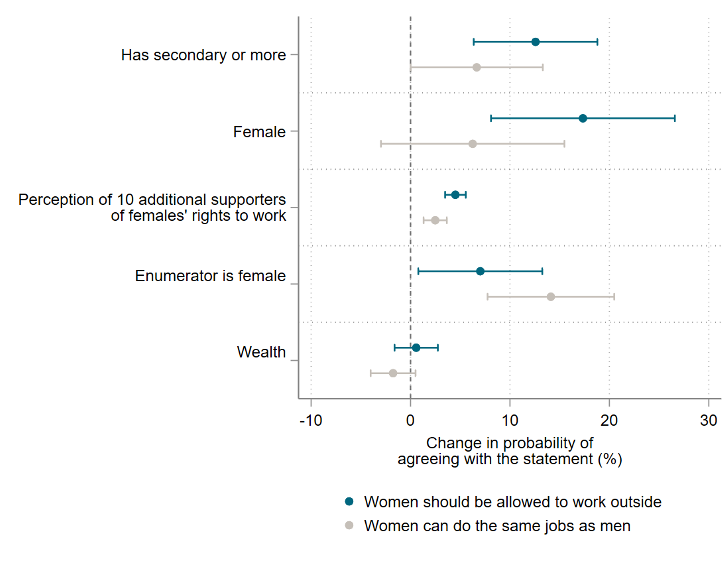

What factors correlate with more progressive attitudes to gender? Our data show that women have more progressive attitudes than men. People with more schooling have more progressive attitudes than those with less. People who were interviewed by a female enumerator also reported more progressive attitudes than those interviewed by a man. Finally, those with more progressive norm perceptions also have more progressive norms themselves (Figure 3).

Each year of schooling is associated with a 1 percent increase in the probability of agreeing with either statement. Those with a secondary school degree or more are 10-12 percent more likely to have a positive gender attitude. Hence increasing education for boys, as well as girls, is an important measure to close gender gaps.

Being interviewed by a female enumerator is associated with a 7 and 14 percent higher likelihood of agreeing with the statement.

The belief that an extra 10 percent of other people support women’s rights to work is associated with a 2-4 percent increase in respondents’ own positive gender attitudes. That is, if a respondent believes half of the public “agree women should work outside the home,” they are 20 percent more likely to privately agree with the same statement than those who believe no one agrees.

Figure 3. Correlates of gender attitudes

Note: sample size of 844 respondents (699 male and 145 female). Marginal effects from a probit model including control for age and age squared.

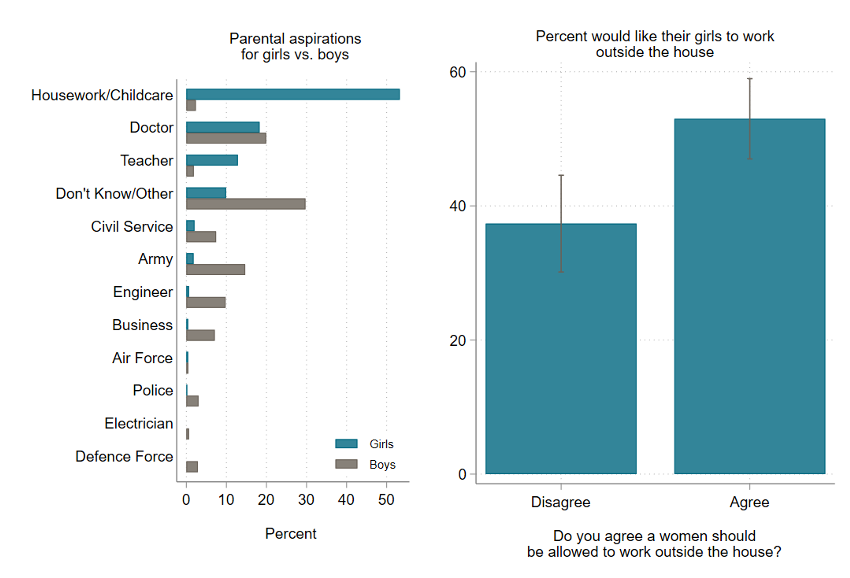

Lesson 4: Parents have different professional aspirations for daughters and sons

Almost all parents of boys (97 percent) want them to work outside the house, compared with only half of parents of girls (47 percent). Most of the latter (53 percent) would like their girls to do housework or childcare. This is similar for both mothers and fathers. Notably, while only a little more than half of the mothers want their own daughter to work outside the house (55 percent) a majority think women generally should be allowed to work outside (82 percent).

There are also clear differences in which professions are deemed suitable for girls. The most common are doctors (18 percent) and teachers (13 percent), professions in which women are over-represented as they have limited interaction with other adult men.

Parents who support women’s rights to work are more likely to want their own daughters to work (53 percent) than those who don’t (37 percent).

Figure 4. Parental aspirations are less diversified for girls compared to boys

Note: Sample size of chart on the left is 592 parents of boys and 442 parents of girls. Chart on the right includes 442 parents of girls only of which 172 disagree and 268 agree with the statement. Vertical bars indicate 95 percent confidence intervals.

Our findings can help promote gender equality in Pakistan

Pakistan has restrictive gender norms coupled with strong misperceptions of gender norms. To promote gender equality, leaders and policy makers can correct this misperception by simply making people aware of what other people think, creating room for positive change.

Aid donors have a strong focus on girls education in Pakistan. Our results suggest that educating boys can also benefit girls, by inculcating more progressive gender norms amongst the next generation of men. And more progressive attitudes to gender can influence parental aspirations for girls in the future.

For more on this survey, check out the dataset.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.