Recommended

Last month Transparency International released the latest version of its Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), the most widely adopted measure of public sector corruption currently available. But as many have pointed out before, the CPI only attempts to measure corruption that originates at home, not whether a country’s policies enable corruption around the globe. This is why countries like the UK and the US still score relatively well on the CPI, despite continuing to play host to illicit cash from poorer countries that are more traditionally considered corrupt.

Transparency International—which itself does a lot of good work to point out the role that rich countries play in enabling transnational corruption—has been open about this limitation of the CPI. Despite this, the index has evolved into a tool that banks and bureaucrats around the world use to assess something that is very different from public sector corruption: the risk of financial crime.

When onboarding new clients, compliance officers at banks have to determine how much of a money laundering risk that person or business poses. One of the things they consider is country risk—the country-level factors that affect their priors about the client’s underlying level of risk. In theory, financial institutions should consider a whole host of factors when making this determination: how compliant the country is with anti-money laundering (AML) standards or how easy the country’s laws make it to fool a compliance officer. While these factors do play a role, it is clear that financial institutions also prefer to reach for the CPI, an easy, widely known measure that they can point to as evidence they are taking country risk seriously.

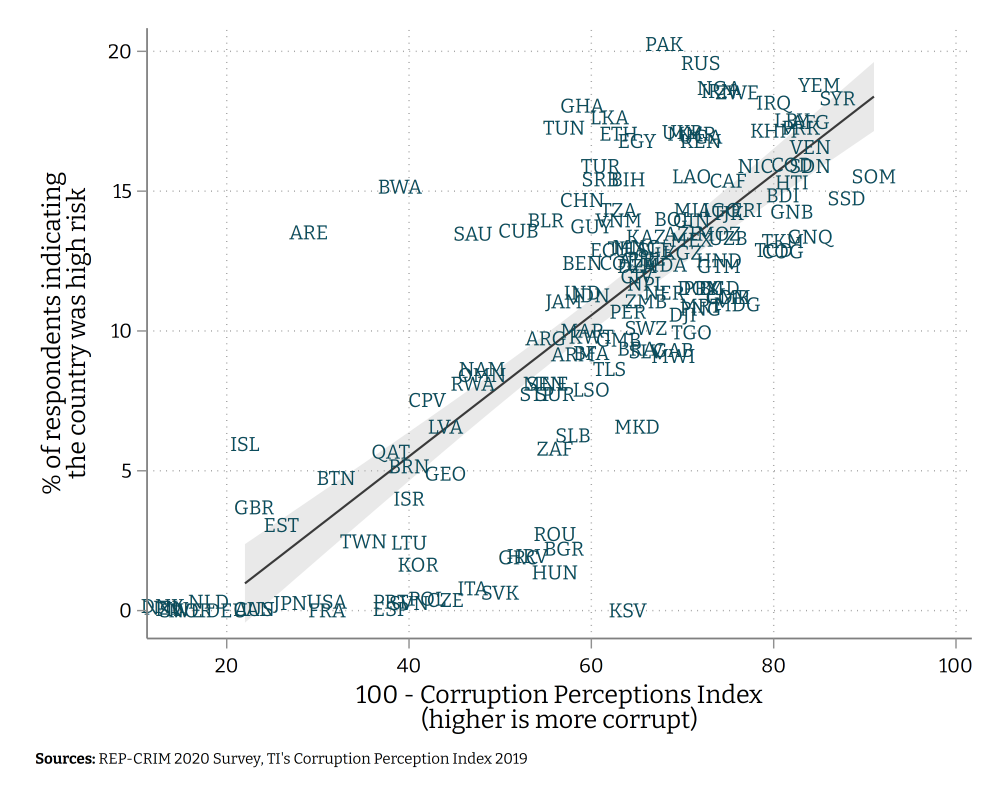

The weight that the CPI has in bank’s risk assessments is at its most evident in the bi-annual REP-CRIM surveys that are run by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority. These surveys ask nearly 2,000 UK financial institutions to indicate whether they consider each jurisdiction they do business in as ‘high risk for financial crime.’ It turns out that the CPI is a strong predictor of how respondents view country risk: moving about twenty points (or two standard deviations) along the CPI is associated with a 10-percentage-point increase in the percent of firms that indicate the country is of a high risk of financial crime (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Transparency International's CPI is a strong predictor of how financial institutions classify financial crime risk

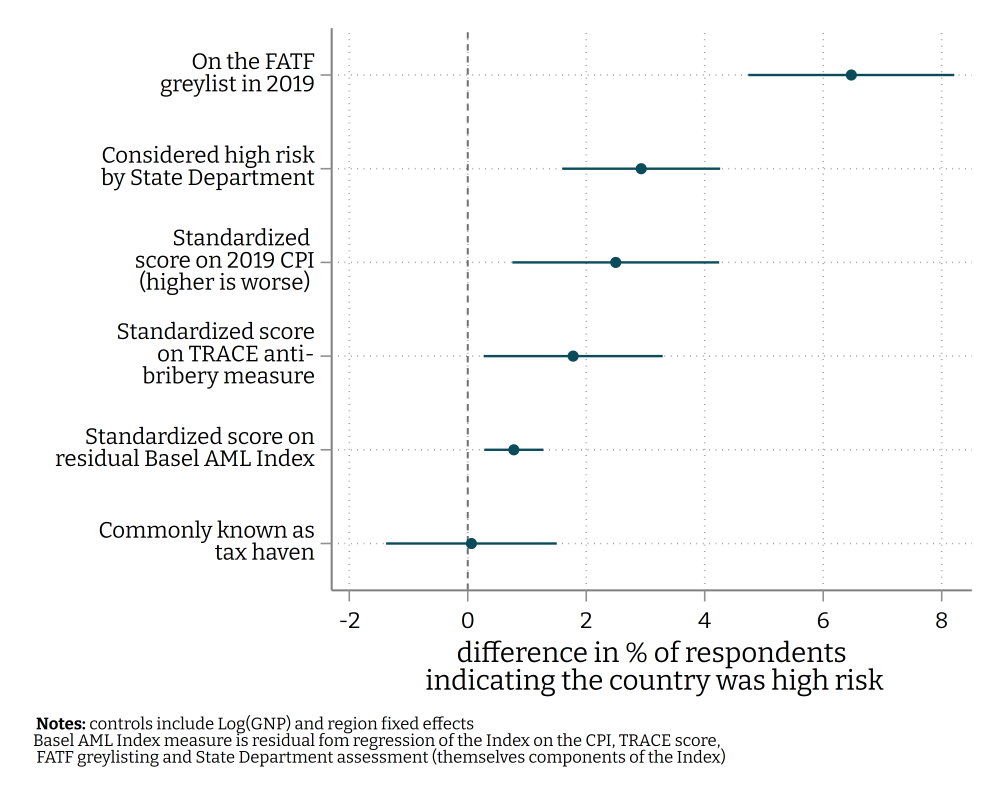

Of course, it may be that countries with weak controls over financial crime just also happen to be corrupt. To better understand which factors stand out in these country risk assessments as well as control for country income, Figure 2 shows the results from a simple regression of the percent of respondents flagging a country as high risk on several different factors: (i) whether the country was on the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) “greylist” of countries not doing enough to fight money laundering, (ii) whether it was considered by the State Department to be a “major money laundering jurisdiction”, (iii) where it scored on the 2019 CPI, (iv) where it ranked on TRACE’s anti-bribery risk score, (v) where it placed on the BASEL AML Index, a popular ‘off the shelf’ measure of money laundering risk and (vi) whether the jurisdiction is a tax haven, known for engaging in the type of financial secrecy that makes it hard for a bank to know who they are doing business with and finally (vii) its GNP per capita and region fixed effects.

Figure 2. Transparency International's CPI is a strong predictor of how financial institutions classify financial crime risk

UK financial institutions do take notice of things they—on paper—are supposed to take notice of: announcements by the FATF and State Department do seem to inform risk assessments. But the CPI still stands out as a major influence on how banks classify risk: even more so than the popular Base AML Index, and much more so than whether a country participates in tax havenry.

So why is it a problem that financial institutions so frequently turn to the CPI to determine how risky a client might be?

The first reason is that—as I’ve argued here before—the CPI isn’t a measure of financial crime, and there is no well-defined relationship between it and the risk of financial crime. In a world where no one can lie about their country of origin, we might expect clients from more corrupt countries to be somewhat riskier than clients from less corrupt countries. But we don’t know enough about that relationship to meaningfully enter it into a risk calculation, nor is there much evidence that being from a highly corrupt country provides any meaningful information after you take it into account other factors, such as that client’s identity, history, the type of economic activity they are engaging in and how easy their financial situation is to parse, all things that compliance officers in banks should be doing anyway.

The second reason is that, in a world where the CPI has been treated as a measure of financial crime risk by banks for decades, anyone looking to engage in a little transnational financial crime will be very eager to hide the fact they are from a highly-corrupt country. The late-husband of Isabel dos Santos—who herself is currently on the lam for pilfering the Angola state—admitted as much in an interview: rich clients from corrupt developing countries rely on tax havens precisely because banks view them with such suspicion. So if every corrupt person goes through great efforts to hide their association with their home country when interacting with financial institutions, clients that don’t bother with this might actually be signaling that they are less risky. Once banks started treating the CPI as a useful measure of the risk of financial crime, it likely ceased to be a useful measure of financial crime risk.

Finally, if we want a global financial system which is designed to efficiently root out dirty money, we need to end the constant cycle of shaming and punishing developing countries for being poor and thus having institutions ill-equipped to fight financial crime. We instead need to focus more on changing behavior in the countries that enable transnational corruption: those whose laws make it easier for people to hide corrupt assets. So long as the financial sector overweights measures like the CPI that are likely to be more strongly correlated with poverty than they are with financial crime, we are unlikely to make as much progress in the fight against illicit flows.

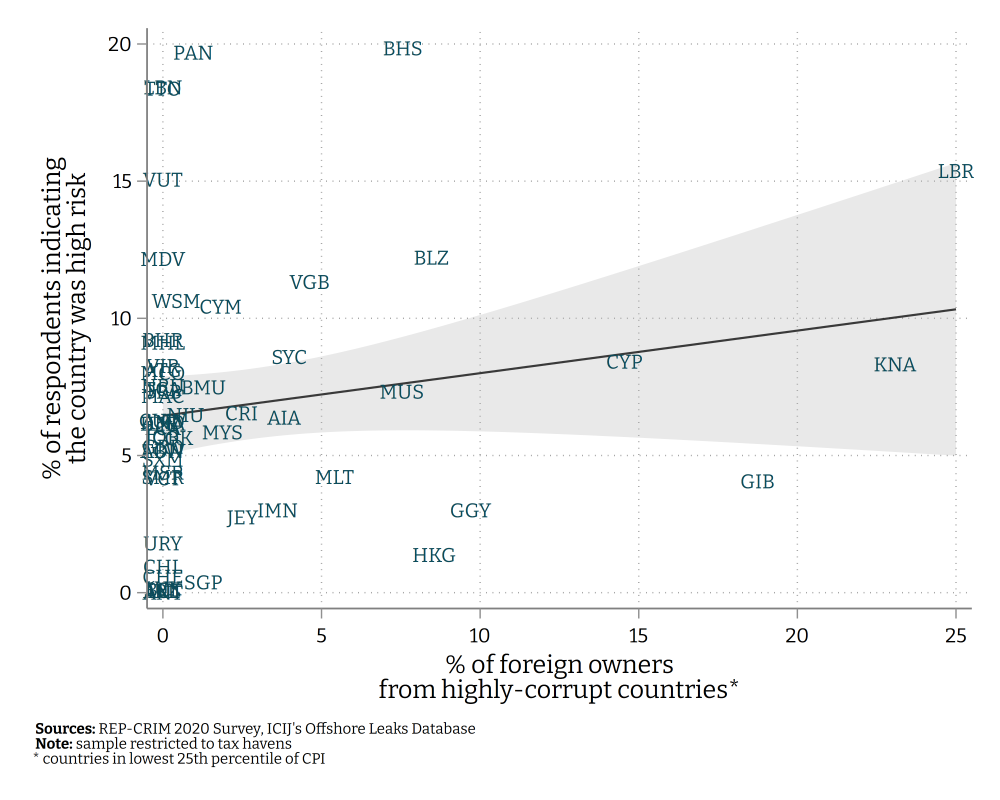

Despite these flaws, banks will continue to use the CPI because it is…. easy. When regulators come knocking, banks are required to show that they have a comprehensive risk management framework, and off-the-shelf measures are both free and give risk assessments an air of legitimacy, even if they are intellectually lazy. But even as they turn away clients based in corrupt countries, they are more than happy to take on clients based in tax havens that are awash in corrupt money. For example, using data from financial leaks such as the Panama Papers and Pandora Papers, we can get a sense of which tax havens around the world take on a lot of business from corrupt countries. But as Figure 3 shows, there’s no visible relationship between being a haven for corrupt money and a bank’s risk score.

Figure 3. Banks don’t particularly care where the corrupt actually keep their money

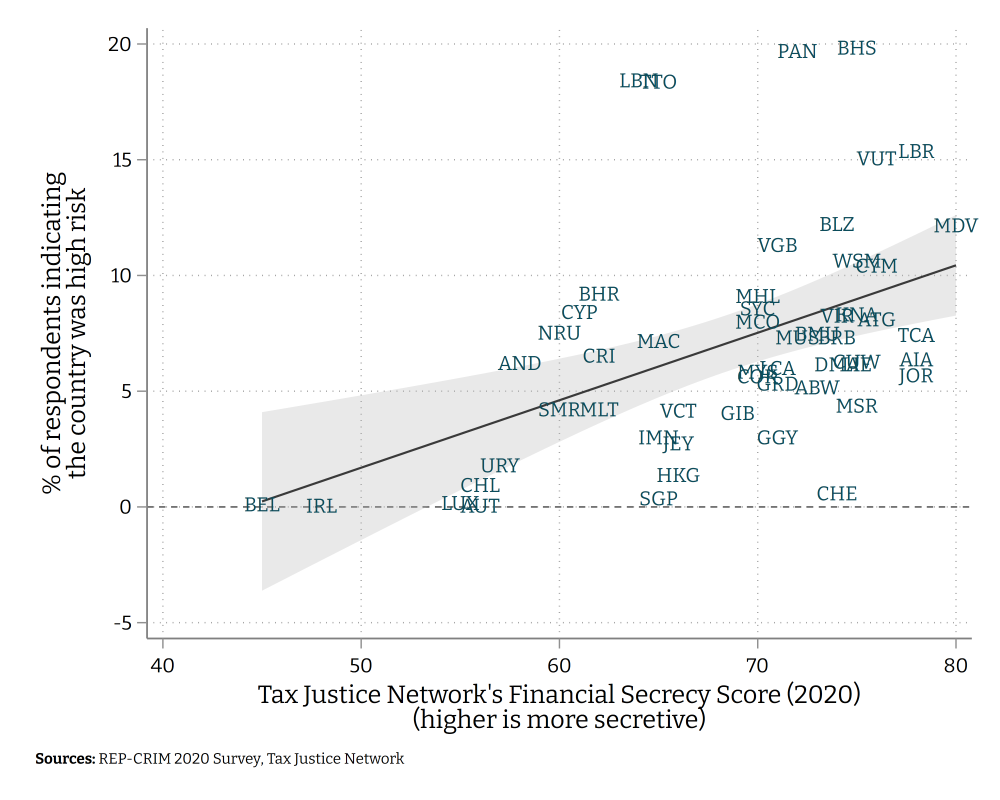

So if the CPI is such a flawed metric for financial crime risk, what would be a good replacement? Jurisdictions that enable financial secrecy—largely tax havens—should be viewed with equal, if not more caution than high-corruption jurisdictions. If you are throwing a party and are worried about the wrong kind of people sneaking in, you should probably be more suspicious of the people who show up wearing a mask. This is backed up by study after study demonstrating that tax havens with a high level of secrecy harbor the assets of tax evaders and the corrupt. And yet, while there is evidence that UK banks are somewhat more wary of countries that score poorly on the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy index (Figure 4), ultimately if you were trying to open an account with a UK bank you would still rather be from a high-secrecy tax haven than a high-corruption country.

Figure 4. Banks do care about secrecy, but not as much as corruption

If we want banks to start taking financial secrecy more seriously and put less weight on the CPI, we need governments and international standard setters to play a stronger role in determining what is and what isn’t a high-risk country. The Financial Action Task Force has historically led the way in identifying high risk jurisdictions, and most recently it began to push countries to do better on financial secrecy, focusing on transparency of company ownership. But it could also take a more active role in saying what should and should not make its way into financial institutions’ risk calculations, or how much weight different factors should be given. Anti-money laundering regulators could also push their financial sectors to put more weight on financial secrecy and less on corruption perceptions (unfortunately, in the UK the Financial Conduct Authority has historically done the opposite). Without a closer examination of the way that the financial sector goes about applying the “risk-based approach,” we risk perpetuating an ineffective system that unfairly excludes honest people from countries that score poorly on the CPI.

Download the data and replication code here.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock