When Indonesian President Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”) meets with President Obama on October 26, climate change will certainly be on the agenda, with the Paris 2015 summit only a month away. Obama should use the opportunity to praise and offer support for the steps Jokowi announced earlier today to address the underlying causes of fires currently consuming vast areas of Indonesia’s forests and peatlands. In particular, Obama should hail Jokowi’s plans to end the opening of peatlands for cultivation and to promote community-based restoration of those already disturbed. Neither head of state should allow his vision to be clouded by spurious claims that proposed solutions will hurt small farmers or infringe on Indonesia’s national sovereignty.

The domestic and international impacts of the fires are both horrific

This year’s fires in Indonesia are a catastrophe of historic proportions for Indonesian and global citizens alike. Dense smoke (euphemistically called “haze”) generated by burning vegetation and soil has created a public health emergency. Press reports indicate that the smoke has affected the respiratory health of millions of people, with 120,000 seeking medical help. Pollution standards are being exceeded to such a degree that the government is considering mounting an evacuation of babies and children from the areas most affected. One of several studies on the impacts of similar fires that burned over 1997–98 estimated exposure to the haze caused 15,600 infant, child, and fetal deaths.

Piled on top of the health costs are the losses from burned property, closed airports, and impacts on tourism revenues. Estimates of the total economic costs of the fires in 1997–98 ranged from $2.8 to $4.8 billion in Indonesia alone. But all of these impacts are also being felt at a regional scale in Southeast Asia. Smoke from Indonesia’s fires is wafting over neighboring countries as far away as Thailand and Vietnam, affecting health, closing schools, and souring Indonesia’s relations with Singapore and Malaysia. One estimate pegs the likely costs of the current fires at $14 billion.

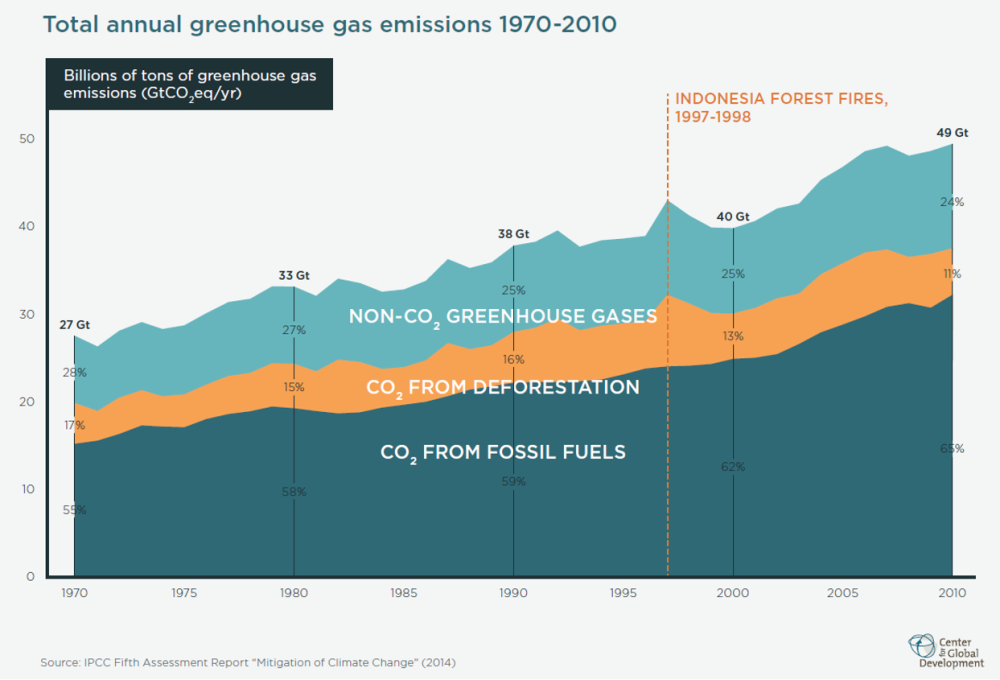

And these are just the direct costs within the region. The whole world will feel the impact of Indonesia’s fires on the global climate. According to Guido van der Werf (as summarized in a useful blog by Nancy Harris and other colleagues at World Resources Institute) the Indonesian fires are currently emitting more emissions on a daily basis than the entire United States. As shown in the figure below, the 1997–98 fires caused a visible spike in globalCO2 emissions, and this year’s fires are on track to do the same. Using the US government’s midpoint estimate of the “social cost of carbon,” the billion tons of emissions from Indonesia’s fires so far this year will cause $37 billion of climate impacts globally (thanks to Michael Wolosin at Climate Advisers for this calculation).

It’s tough to quit smoking

As my husband would say, “If it were easy to quit smoking, more people would do it.” It’s the same with the fires: if it were easy to end the burning, Jokowi would have done it last year, after visiting an area of scorched earth in Riau province soon after his inauguration. He inherited this problem, decades in the making, and solving it will require immense determination to follow through on politically difficult reforms.

As described in a background paper by Indonesian journalists Metta Dharmasaputra and Ade Wahudi, the origins of Indonesia’s fire-prone landscapes are deeply embedded in the political economy of the nation’s forest resources. Under previous administrations, the government issued permits for forest exploitation to politically connected elites, often through corrupt practices. Commercial forest clearing also generated pervasive conflicts over land rights. Of particular relevance to the fires, large areas of peatlands have been cleared and drained to plant fast-growing timber to feed pulp mills, and to establish oil palm plantations to supply the world’s most popular vegetable oil.

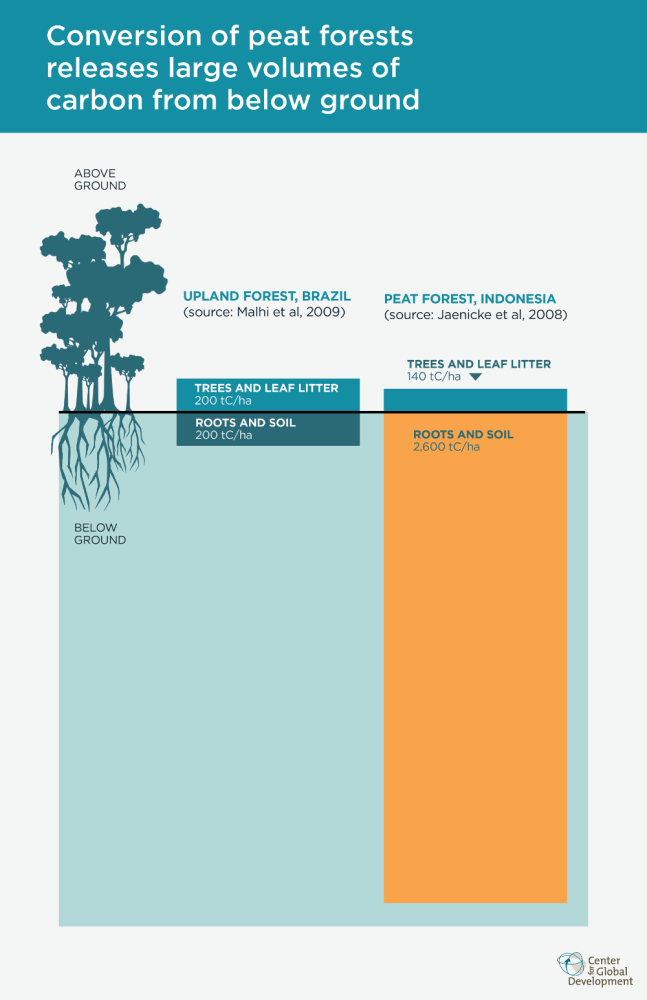

But once cleared and drained, rich organic peat soils are easy to ignite, explaining why more than half of the current “hot spots” are on peatlands. Even in the absence of burning, disturbed peatlands are the “gift that keeps on giving” (in a bad way) in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, as carbon embodied in deep deposits of organic matter accumulated over centuries is liberated into the atmosphere through decay. The figure below shows how much more carbon is stored below ground in peat swamps compared to the amount stored in above-ground vegetation.

Recent efforts mobilized by the Jokowi administration to fight the fires and hold responsible parties accountable for illegal burning are necessary and welcome. But today’s announcement reflects a dawning realization that the only way to prevent the recurrence of these catastrophic fires, and to reduce Indonesia’s climate emissions, is to fundamentally shift the trajectory of land management, especially the development of peatlands.

Today’s announcement of an immediate moratorium on the clearing and draining of remaining undisturbed peatlands — including areas already licensed for development — is a critical first step to stop the bleeding. Industry leaders in the pulp and paper and palm oil sectors have already pledged to get deforestation and peatland conversion out of their supply chains in response to civil society advocacy and international market pressures. At the UN Secretary General’s Climate Summit last year in New York, CEOs of four of Indonesia’s largest palm oil producers signed the Indonesian Palm Oil Pledge (IPOP) in collaboration with the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (KADIN), and additional countries have since joined.

In today’s announcement, Jokowi has also gone a step further, directing that disturbed peatlands be restored to a wetter, less flammable state. Doing so would require working with companies and local communities to block drainage canals and shift agricultural production to paludiculture, that is, crops that tolerate wet soils. It won’t be easy: a CGD policy paper by Robin Davies provides a cautionary tale of how political and bureaucratic obstacles killed a peatland restoration project launched with great fanfare by the governments of Australia and Indonesia in 2008.

Smoke gets in your eyes

When your heart's on fire,

You must realize, smoke gets in your eyes

—The Platters

Jokowi’s announcements are especially meaningful in light of domestic opposition. Allies of business as usual have put up a smokescreen, claiming that no-deforestation, no-peat commitments such as those pledged by IPOP companies will hurt smallholders, and that in any case, foreigners should not be dictating standards for Indonesia. The narrative is intended to appeal to nationalistic sensitivities, and to Jokowi’s well-known priority of standing up for the little guy.

But in fact the IPOP pledge includes a commitment to helping smallholders, and ending deforestation and peatland conversion is compatible with increasing smallholder productivity. Smallholders are also stakeholders in repositioning Indonesia in the global market as a source of “green” products. Mansuetus Darto, head of the Oil Palm Smallholders Union (SPKS), believes that the government’s focus should be on enhancing productivity rather than expanding area under cultivation.

Smallholders are among those suffering health and other impacts from the fires. More broadly, it is increasingly clear that maintaining forest ecosystems provides benefits to agricultural systems. In a recent CGD podcast, Juliana Santiago head of the Amazon Fund department at Brazil’s development bank (BNDES), argued that part of Brazil’s success in reducing deforestation was due to a realization that “our economy depended on maintaining the forest.”

What could the United States do?

Bilateral meetings earlier this year with the leaders of Brazil and China have resulted in joint announcements related to climate change, so we can expect one for Indonesia as well. Having heeded the advice of Indonesian activists and academics that addressing the underlying causes of the fires is in the domestic self-interest (as well as being essential to reducing emissions), Jokowi’s announcement now prompts the question of what the United States can do.

First, President Obama should provide strong praise and encouragement for the announcements made by President Widodo. Although Jokowi is not as interested as his predecessor in seeking the limelight of the international stage, recognizing and applauding his leadership is still important.

Ideally, in addition to short-term humanitarian support, Obama would be in a position to put up some real money to recognize the US interest in Jokowi’s success in implementing a longer-term agenda. Offering such support on a payment-for-performance basis would be a way to respect Indonesia’s sovereignty in figuring out how to reform land-use, while strengthening the position of advocates for reform. In a blog penned this time last year, I wrote:

it’s critical that other countries thread the needle between supportive engagement and the appearance of inappropriate engagement in domestic affairs. Making explicit commitments to reward Indonesia’s success in implementing its own strategy to reduce deforestation … would be an obvious way forward.

And as described in a CGD policy paper, an existing payment-for-performance agreement with Norway has helped to usher in new norms of transparency and steps toward recognition of indigenous rights, both of which will critical elements of a strategy for long-term fire control. The agreement also gave birth to a moratorium on new forest licenses and a national “one map” initiative, both of which were reinforced in today’s announcement.

But in the absence of Congressional support for a significant financial pledge, an enhanced portfolio of smaller caliber partnerships could also make a difference. Obama could reiterate US commitment to the Tropical Forest Alliance (TFA), a partnership formed in 2012 designed to reduce deforestation from globally traded commodities in cooperation with producer and consumer countries and companies throughout the supply chain. As described in this CGD brief, such initiatives can help ensure that developing country efforts to shift production to a legal and sustainable basis are rewarded by the market. Indonesians would likely welcome enhanced scientific cooperation on forest and peatland management.

Support targeted at increasing the productivity of smallholders could also be useful if clearly linked to the objective of reducing deforestation and peatland conversion. (Smallholder finance decoupled from forest and peatland protection could inadvertently lead to increased clearing.) Support for community involvement in peatland restoration would be one way to both support rural incomes and prevent future fires.

The good news is that it’s possible to do both.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.