The biometrics revolution has enabled a growing number of countries to build more robust ID systems, while providing their citizens with greater access to rights and economic opportunities. The biometric identifier of choice for most of these systems has been fingerprints. Despite its recognized accuracy, reliability and security iris recognition is less widely used, largely due to the high cost of iris readers. A binocular iris reader represents a substantial investment of several hundred dollars and even monocular readers run at several times the cost of a fingerprint scanner. This is about to change dramatically.

A new iris-recognition enabled tablet was launched in India at the end of May, providing a low-cost and potentially more effective method for authenticating the identities of people enrolled in the ground-breaking Aadhaar program. The tablet can be used for multiple purposes, including e-KYC (Know Your Customer) and child enrollment programs where very young children can be authenticated through the iris of their parents. It retails for around $200 and at least another six models are following suit. The cost of incorporating iris recognition into a mobile device has fallen to only around $3—$5 in mass production. With such a small incremental cost it is more than likely that an increasing number of mobiles and tablets will come to incorporate iris technology.

This represents an enormous potential expansion in biometric readers, considering that the number of smartphone users in the world now tops 2 billion people. The Bangalore-based developers of the tablet have placed its identity software development kit in the public domain so that developers can create applications where the iris scan can be used at ration shops, for disbursing payments under India’s gigantic MNREGA program, for pension payments and any number of e-citizen services.

Why is this significant for development? Iris has many advantages, especially for low-income populations with worn fingerprints due to heavy manual labor. Eyes are self-cleaning and image capture is performed without physical contact with the reader. One field-based comparison of iris and fingerprints comes from proof-of-concept tests carried out by the Unique Identification Authority of India. Our synthesis of the results indicate that Iris trumped fingerprints. Iris scans were far more inclusive than fingerprints, with fewer people unable to provide them at acceptable quality. They were also more precise for authentication, with a better tradeoff curve between errors of acceptance and rejection. Moreover, tightening up the tolerance for False Acceptance (potential fraud) to as low as one chance in one million (one hundred times the security afforded by a 4-digit PIN) resulted in almost no increase in the percentage of people denied recognition, either because of False Rejection or Failure to Capture the iris image. This remained almost stable at around 1 percent, confirming that iris recognition technology is both very secure and inclusive.

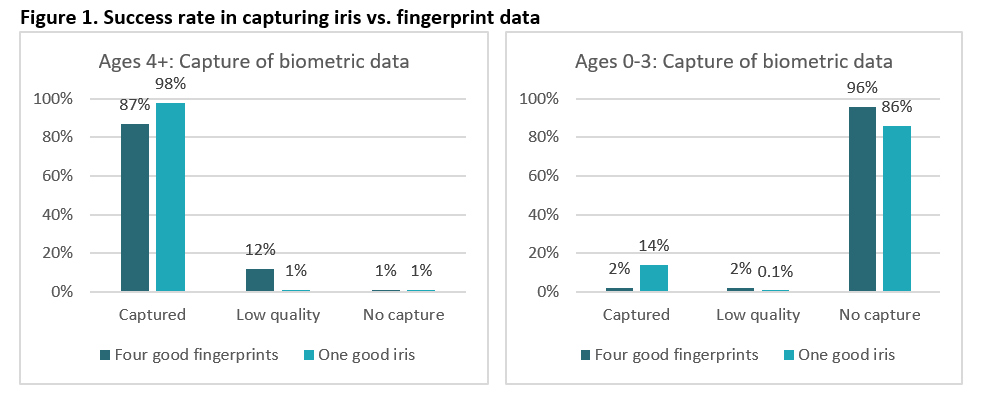

Another comparison of iris and fingerprints in difficult field conditions comes from a UNHCR project in Malawi—Biometrics in a Humanitarian Context. This aimed to test whether complex biometric solutions could be deployed in environments commonly faced by UNHCR. The four week exercise involved 16,849 refugees, 140 staff and 16 enrolment stations with a focus on the ease of acquiring high-quality biometrics. Iris scored far higher than fingerprints in terms of ease of use, speed, and overall preference. Many fingers required re-capture. The hardware required cleaning four times a day, and “children were hardest to capture as their hands were often dirty or sweaty”. Eighty percent of respondents rated iris capture “easy” compared with 40 percent for fingerprints, and virtually all operators preferred it to fingerprint capture. Over 13 percent of refugees over the age of four were unable to provide 4 good fingerprints, but only 2 percent were unable to provide a high-quality iris (Figure 1).

Transitioning from legacy technologies takes time. But with iris readers able to be embedded into almost-ubiquitous mobile devices at far less than the cost of a stand-alone fingerprint reader, we can expect major changes in how identification systems interact with people, whether at the point of delivery of public services or for them to authenticate themselves for private transactions. This development will also help to resolve concerns about excluding beneficiaries on the basis of failure to authenticate using only fingerprints, opening the gates for more widespread deployment of biometric technology to make service delivery more efficient.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.