In this blog we preview a new measure of country effort to improve girl’s education—The Girl’s Education Policy Index.

Education for girls is hailed as one of the best investments in development by politicians, activists, and celebrities alike. The investment case is supported by numerous studies examining the positive impacts of girls’ education across contexts, linking it to better child health, higher labour market participation, and reduced child marriage.

Progress toward girls’ educational outcomes is generally measured through enrolment rates and learning levels. However, there is little systematic data on the policies that are conducive to more and better education for girls.

In this blog we preview and invite input on the new Girl’s Education Policy Index: a curated set of indicators to measure the policy effort of countries, which governments control, rather than their education outcomes, which are measured in other ways. By highlighting different countries’ specific strengths and weaknesses, we can identify where and which policy efforts governments and donors can take to most effectively deliver better outcomes for girls.

Our data and provisional results are here. As we develop the index, we welcome your comments and feedback on how it can be improved.

The index

The index assesses effective policies on five components: spending on education, sexual health, safety, labour market opportunities, and role models. Each of the 18 indicators has been selected based on three criteria: (1) having some empirical evidence that it matters for girl’s schooling, (2) being a policy measure that governments can directly address, and (3) having comparable data across a large number of countries.

Table 1. Components and indicators

| Category | Indicator | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Financial Barriers | 1.1 | Government expenditure on education per child (% of GDP per capita) |

| 1.2 | Fees to attend school | |

| 1.3 | Incentives for girls to attend school (cash transfers) | |

| 2. Sexual & Reproductive Health | 2.1 | Ban on child marriage |

| 2.2 | Legal restrictions on the availability of contraception | |

| 2.3 | Laws mandate sexuality education in schools | |

| 2.4 | Separate toilets and sanitation facilities | |

| 3. Child Safety | 3.1 | Programs to reduce violence by school staff |

| 3.2 | National action plan to reduce violence in schools | |

| 3.3 | Ban on corporal punishment | |

| 4. Labour Market Opportunities | 4.1 | Does the law mandate nondiscrimination based on gender in employment? |

| 4.2 | Does the law mandate equal remuneration for work of equal value? | |

| 4.3 | Does the law prohibit discrimination by creditors on the basis of sex or gender? | |

| 4.4 | Is sexual harassment of women explicitly prohibited in the workplace? | |

| 5. Role Models | 5.1 | % Female primary teachers |

| 5.2 | % Female secondary teachers | |

| 5.3 | % Female public sector workers | |

| 5.4 | Quotas for female parliamentarians |

We road tested the index as currently constructed to see what preliminary insights it could offer on countries’ policy efforts on girls’ education with the indicators as we have laid out below. The top countries are primarily rich Western European countries, although not necessarily the ones that typically top development rankings. Kenya stands out as a lower-middle income country that ranks 18th globally, thanks to high scores on each of the five subcomponents. Drilling down into the detailed indicators, Kenya spends a below average share of GDP per capita on education per child (14 percent, compared to a global average of 20 percent), but has no tuition fees for primary or secondary school, has a high minimum age of marriage for girls (18), no legal restrictions on access to contraception, put policies and plans in place to reduce violence in schools, has laws guaranteeing non-discrimination against women at work, and reserved seats in parliament for women. No one region dominates when we look at the top ten performing low- and low-middle-income countries.

Top 20 countries (provisional rankings)

Top 10 Low- and lower-middle-income countries (provisional rankings)

The lowest-ranked countries offer some insight as to where donors might want to prioritise their efforts. Thirteen of the 20 lowest ranked countries are in sub-Saharan Africa. The bottom-ranked country is Somalia, which has low scores across the board: low spending, low access to sexual and reproductive health services, weak child safety rules, weak labour market opportunities for women, and weak role models for girls.

Bottom 20 countries (provisional rankings)

Top countries on each component

Although still a work in progress, the index points to countries that perform particularly well on the indicators we’ve identified. (As we refine the index, these rankings might change.)

1. Financial barriers. The top five countries here are Cuba, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Portugal. They each have no fees for any of primary or secondary school, national cash transfer programmes with wide reach, and spend a large share of GDP per capita on education (per child).

2. Sexual and reproductive health. The top five countries are China, Sweden, Denmark, Bhutan, and Kenya. All have a legal minimum age of marriage of 18 for girls, and few legal restrictions on access to contraception for girls.

3. Child safety. Twenty-one countries achieve the maximum score for this component, including Thailand, Syria, Sudan, Morocco, and Indonesia. All have programs designed to reduce violence by school staff, funded national action plans to reduce violence in schools, and bans on corporal punishment.

4. Labour market opportunities. Thirty-six countries achieve the maximum score for this component, including Angola, Guinea, Morocco, Philippines, South Africa, Vietnam, and Zambia. All have laws on non-discrimination at work, on equal pay, on equal access to credit, and prohibitions on harassment at work.

5. Role models. The top five countries here are all Eastern and Central European countries: Czech Republic, Latvia, Kyrgyz Republic, Belarus, and Russia. They all have high shares of female teachers and female public sector workers.

Why these indicators?

1. Spending

We can’t escape from the fact that money matters in education. There are always efficiencies to be had, but the best evidence suggests that expanding access costs money. Building new schools where they don’t exist costs money and boosts schooling. A large literature shows that removing school fees increases school attendance and that even relatively low costs can be a barrier to girls attending school. Programs that eliminate cost barriers have shown promising results. To take just one recent example, Ayibor and Chen (2019) find that across 21 African countries, access to free primary school increases average schooling of adult women by 1.4 years. A 2016 rigorous review found that 12 of 15 studies on the effect of cash transfers on girls schooling showed a statistically significant improvements

2. Sexual and reproductive health

Early marriage and pregnancy are key barriers to education for too many girls. Though unpicking causality is hard, instrumental variable approaches suggest that each year that marriage is delayed (due to exogenous factors) leads to an increase in schooling of 30-50 percent of a year. In the index we focus on the legal minimum age of marriage as a measure of policy intent. Minimum age of marriage laws are not enforced in many countries, but there is evidence, for example from Ethiopia and India, that introducing a higher minimum age of marriage can still have an effect even where adherence is not perfect. Access to single-sex bathrooms at school is important for teenage girls. Similarly, access to reproductive health services, and sexual and health education.

3. Child safety

Many girls are kept out of school or may drop out of school because of fears about their safety. Violence in schools is common and one of the main reasons for children to dislike school. Over half of eight-year-olds in India, Vietnam, Ethiopia, and Peru saw a teacher use corporal punishment in the last week. Between one and five percent of teenage girls have experienced sexual abuse at school in many developing countries. As many as one in ten Senegalese and Zambian 15-year-olds have experienced sexual harassment by a teacher.

4. Labour market opportunities

A key driver of girl’s schooling is whether going to school pays off in the job market or not. For example, Heath and Mobarak (2015)show that the opening of garment factories in Bangladesh increased the labour market gains from going to school for girls, resulting in more girls going to school. Similarly, advertising new business process outsourcing jobs in India led to young women delaying marriage and childbirth, and instead getting a job or more education.

5. Role models

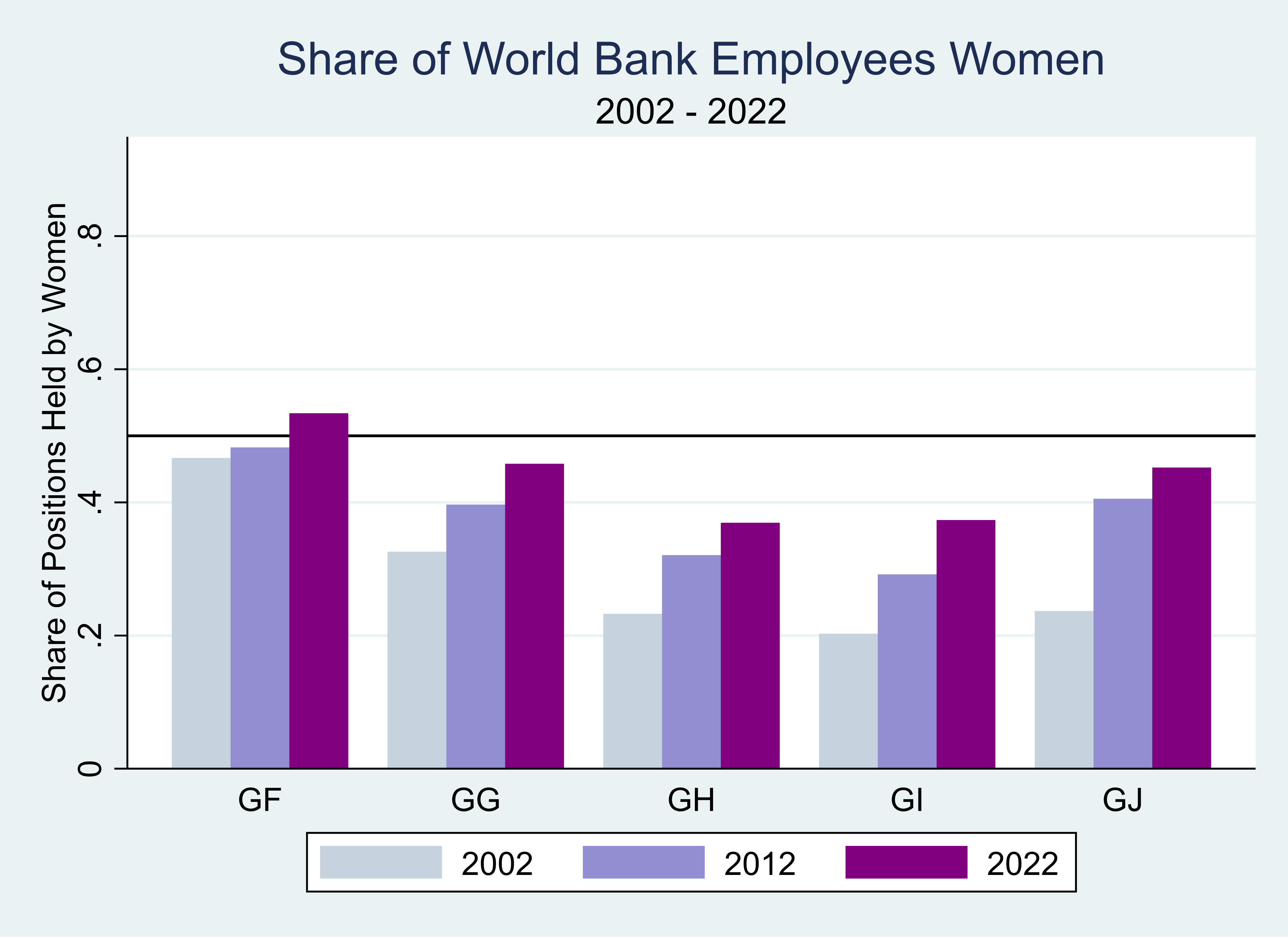

It’s not just the availability of job opportunities for women that matters for girls schooling, but girl’s perception of the availability of job opportunities. An obvious place to start is in schools—teaching can be a major source of employment for women, and research also shows that in some places girls do better when they have female teachers, and boys no worse. We also consider whether quotas are in place for female parliamentarians. When village council positions are reserved for women in India, evidence suggests that teenage girls gain higher aspirations and spend less time on household chores.

What is not in the index?

The index is focused on policy action that governments and international partners could plausibly influence. It does not include relevant outcomes, such as changes in social norms.

It also focuses on policy actions for which there is internationally comparable data. We do not include important policy issues such as bias in curricula, the availability of modern contraception (as opposed to legal restrictions to access, which is included), or average distance to school, for which such data does not exist for a large sample of countries (Family Planning 2020 collates DHS data on contraceptive use for a large sample of countries, but we do not include this as use is an outcome not a policy. They also collate data on provision but only for a much smaller sample of countries, so we do not include that data either).

We recognise that there is a distinction between pure policy actions—for example legislating against child marriage—and "intermediate" outcomes—such as increasing the share of female teachers or number of schools with single sex toilets. In the latter case, we have included them if our judgement is that it is something close to a policy.

A particularly important omission are efforts to improve the quality of school—for example whether or not a government has implemented an evidence-based, early grade reading programme. This is important but difficult to measure systematically and compare across countries. The quality of schooling is typically measured through learning assessments—an outcome that is also highly influenced by national income.

Construction of the index

Each indicator is first standardised to mean zero and standard deviation of one, so that they each have equal weight in the index. We then create a score for each component that is the simple average of indicators within the component. At this stage we simply ignore missing data, which is equivalent to assigning the mean value to any country with missing data for an indicator.

Further refinement of the index would include a more detailed investigation of likely values for missing data—for example in some cases it may make more sense to assign countries the lowest possible score if data is missing, rather than the average. We then average across the five components for an overall index score. The z-score is then transformed so that each country is shown as a percentage of the best possible score. We omit the smallest countries from the index (those with a population below 100,000 people), as well as countries with all data missing for two or more of the five components (this includes Aruba, Fiji, Guam, Japan, Macao, New Caledonia, Puerto Rico, French Polynesia, and US Virgin Islands).

Validation

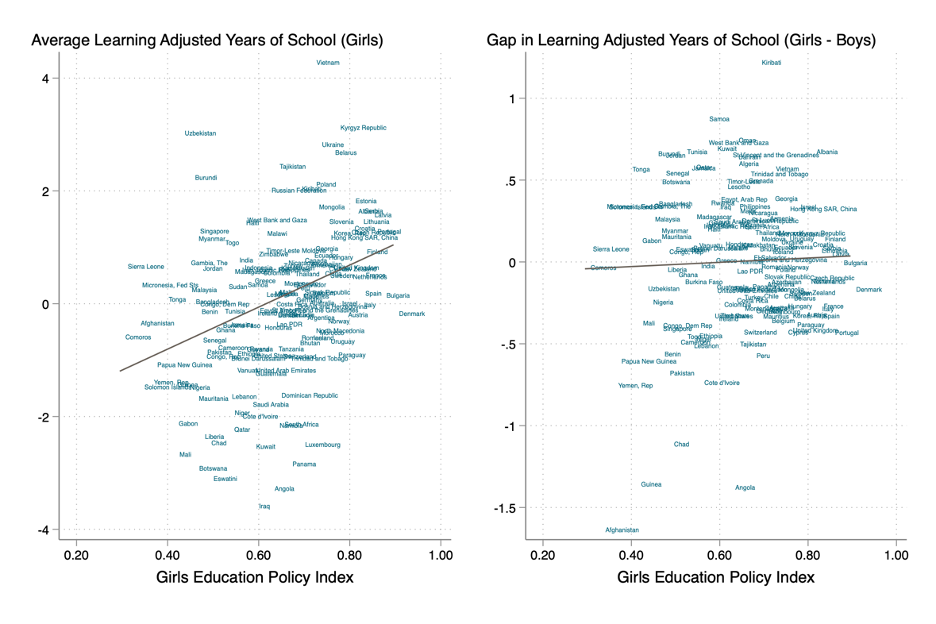

Does this index measure anything useful? The justification for the inclusion of individual indicators is primarily through the well-identified experimental and quasi-experimental studies discussed above. However we can also compare the index value across countries with composite measures of education outcomes. We see a strong correlation between the index and Learning Adjusted average Years of Schooling (LAYS) for girls, even after controlling for per capita GDP. We don’t see a correlation with the gap in LAYS between girls and boys, but then several of the indicators we include in the index are expected to help both girls and boys. We also see statistically significant correlations between most of the individual indicators and learning adjusted schooling.

What data are missing? What have we done wrong? Is this useful? Please get in touch with Lee (lcrawfurd@cgdev.org) or Susannah (shares@cgdev.org). Once we've refined our methodology and taken onboard feedback, we'll be publishing the final Index—look for that in the near future.

For the full data see this spreadsheet.

Once we've refined our methodology and taken onboard feedback, we'll be publishing the final Index—look for that in the near future.

Thanks to Masood Ahmed, Ranil Dissanayake, Charles Kenny, and colleagues in the education program for their comments on an earlier draft of this blog post.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.