A key goal of tax-and-spending policies is to alleviate poverty by redistributing income from the haves to the have-nots. The extent that this is possible depends on the balance between the number of higher earners and the number of poor people, and the efficiency of the mechanisms used.

Redistribution potential

Until a few years ago developing countries did not have the capacity to reduce poverty in this way, as Martin Ravillion at the World Bank calculated; in most countries there were just too few rich people and too many poor people. But over the past decade, economic growth has reduced the number of people living in extreme poverty, and increased the numbers who could afford to pay more tax. Rising inequality strengthens both the moral and practical case for redistribution.

When Chris Hoy and Andy Sumner ran the same calculation last year they found that, in theory (if there were no administration costs, and cash transfers could be perfectly targeted) middle income countries such as China, India, Brazil, and Indonesia could eliminate three quarters of global poverty through tax-and-redistribution. In practice many countries have developed cash transfer programs, such as Brazil’s Bolsa Familia, China’s Dibao, and Indonesia’s Bantuan Langsung Sementara Masyrakat (BLSM), which reached some 700 million people.

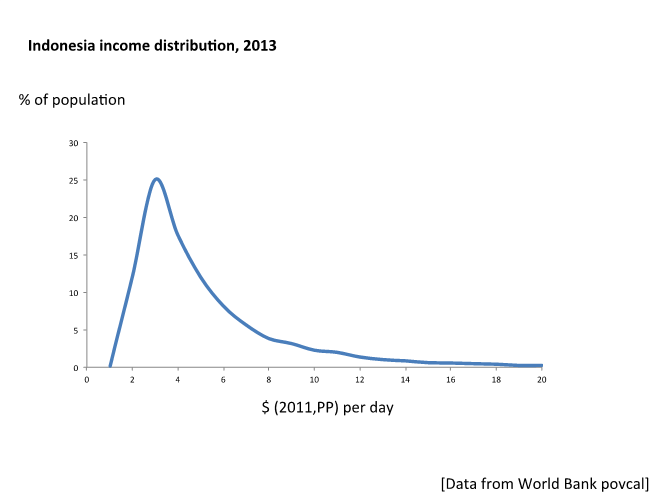

But while increasing affluence creates greater potential for redistribution, it quickly runs into limits. When Hoy and Sumner talk about “taxing the rich,” the group of taxpayers they are looking at is mainly comprised of people who are barely affluent themselves. For example, they calculate that to bring the poorest up to $1.90 (2011, PPP) requires a marginal tax of up to 2 percent in Brazil, China, and South Africa, rising to 6 percent in Indonesia and 23 percent in India, for everyone whose income is more than $10 a day (on top of taxes for other areas of public spending).

Furthermore, the apparent affordability revealed by these calculations depends heavily on assuming that payments can be targeted (at no additional cost) precisely to bring individuals up to the poverty line by a few cents a day. In actuality, cash transfers are chunkier sums distributed less precisely. As Berk Özler at the World Bank points out, this is not a trivial matter in working out how many people can be brought out of poverty with each dollar of redistribution (and as Lant Pritchett reminds us, trying to get more people just over any particular line is not the point, because there is no line).

The inconvenient truth is that in practice the combination of tax, spending, and redistribution undertaken by governments often makes significant numbers of poor people worse off. As Nora Lustig’s Commitment to Equity project highlights, the net result of taxes and benefits in Armenia, Bolivia, Brazil, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania is that more people are below the $2.50 poverty line than before. In Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, and Tunisia between one-quarter and two-thirds of the poor have less income as a result of the fiscal system.

In other words: there is capacity for redistribution to reduce poverty in many middle-income countries, but it is not painless or unlimited, rather it is less affordable than the sums-on-paper make it appear and it involves raising taxes (or reducing subsidies) for a broad set of taxpayers on moderate incomes.

Even it up in Indonesia?

Last week, Oxfam released a report on Inequality in Indonesia which gave the impression of a vast capacity to increase public spending and redistribution, by focusing on taxing the mega rich. Its “killer facts” included:

- If Indonesia had reached its full tax potential in 2015 it could have raised an extra $63 billion, enough to increase health spending 9x over.

- The amount of money the richest Indonesian earns annually from his wealth is enough to bring 20 million people out of poverty.

- In 2014, $100 billion flowed from Indonesia into tax havens, equivalent to nearly 10x the education budget.

Inequality in Indonesia is high and on the rise. Household surveys show that most of the population consume less than $10 (PPP) a day, while the Forbes rich-list shows 32 Indonesian billionaires. The country only collects about 11 percent of GDP as tax, whereas the IMF estimates it could collect up to 21 percent. So certainly there is a need for more and better taxation in Indonesia, and for it to be more progressive.

But is Oxfam being overoptimistic about the scale of redistribution afforded by tapping billionaires and tax havens?

Wishful thinking about tax

The Richest Indonesian, Budi Hartono, is worth $8.1 billion. Oxfam calculates that the money his assets generate annually would be enough to “eradicate extreme poverty in Indonesia.” However, this turns out to be based on a misunderstanding (as Laurence Chandy points out below—this section has been updated to reflect his comments).

21 million people remain below the extreme poverty line, in Indonesia and the average poverty gap in 2014 was 1.25 percent. Oxfam calculate that this means that extreme poverty can be eliminated for a little over 2 cents per day, or a total of $182 million, which they note could be more than covered by the $324 million returns from Budi Hartono’s wealth. However as Laurence Chandy points out, this is a mistake; the actual gap is 29c, or $2.2 billion altogether. So it turns out that a 100% tax on Budi Hartano’s income would not bring 20 million people out of extreme poverty, but rather would give them 4c extra per day, raising their incomes by 2%.

Oxfam recommends that Indonesia should raise the top rate of income tax to 65 percent for the 350 or so mega-rich people in the country, introduce a wealth tax and raise inheritance tax. However, it seems unlikely that concentrating fiscal reforms which target just the few at the top would generate anything close to the extra $63 billion implied by the IMF’s estimate of the country’s tax potential. As a very rough calculation, raising the top tax rate to 65 percent on the presumed earnings of Indonesia’s next 32 billionaires (assuming simplistically that they don’t react in any way) could raise an additional $0.9 billion a year. Indonesia’s fuel subsidies in contrast were worth $28 billion but affect many more people, and have been reformed after many false starts.

Wishful thinking about tax havens

As the challenge of fuel subsidy reforms highlights, raising more revenues more progressively means negotiating a politically difficult settlement between governments and citizens. However Oxfam instead point to what they believe are massive flows of untaxed income going offshore: $100 billion flowing from Indonesia into tax havens in 2014.

This number appears to be wishful thinking. The report indicates the numbers are based on analysis of data from the IMF Coordinated Direct Investment Survey (CDIS), which Oxfam interprets as showing that $101 billion was invested from Indonesia into tax havens in 2015, compared with $53 billion in 2009 (page 22 and footnote 137).

But firstly, the CDIS figures are stocks, rather than flows. And secondly, as far as the IMF data reports the total stock of outward investment from Indonesia to all other countries in 2015 stood at $25 billion.

I think that the source of the $100 billion figure may be a muddle and a mistake. If you look at the CDIS data for inward investment positions to Indonesia in 2015 and add together investment from Singapore, the Netherlands, Mauritius, and small island states like the Seychelles, the total is around $100 billion. If you do the same thing in 2009, the total is around $50 billion. These are stocks, not flows. And they are inward not outward investment positions. If this is the analysis that shows “$100 billion flowed from Indonesia into tax havens, equivalent to nearly 10 times the education budget in that year,” it appears to be a mistake.

Redistribution has a role to play, alongside economic growth in enabling more people to attain prosperity. Negotiating the trade-offs and difficult choices to be made is politically difficult and requires honest debates—not wishful thinking.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.