A dispiriting exercise in blame-shifting took place in early June at the World Trade Organization (WTO). Trade negotiators have been trying for months to find a few items where they agree so they can declare the Bali ministerial meeting in December a success, and then bury the broader Doha Round. Pretty much everyone accepts that a proposed agreement on trade facilitation would be useful and that is the most likely issue on which members could find consensus. Many countries would also like to move forward on at least some, relatively narrow, agricultural issues and on issues that could promote the integration of the least developed countries (LDCs). But in Geneva, everyone wants to get something, no one wants to give anything, and everyone is blaming everyone else for the deadlock.

All the big players share the blame.

India insists that it cannot agree to trade facilitation without getting something on agriculture. It is promoting a proposal to allow developing-country governments more flexibility to purchase commodities at above-market prices and stockpile them for food security reasons. There is a broad willingness among WTO members to address food security and openness to considering how grain reserves, though costly, could be a part of that. But paying above market prices is a blatantly trade-distorting subsidy and unnecessary. The proposal almost seems designed to block any deal.

The WTO G20 group of developing country agricultural exporters, including Brazil, made a perfectly reasonable proposal for developed countries to lower their export subsidy ceilings by half, as a step towards the goal of complete elimination. The G20 also proposes changes to export credit guarantee terms to reduce the potential subsidy element. The European Union, the major user of export subsidies in years past, demurred. The table highlights why this puzzles me.

| European Union Outlays and Commitments for Export Subsidies (million euros) | ||||

|

| Budgetary outlays | WTO commitment | Outlay/ Commitment | |

| 1995 | 4884.9 | 11750.9 | 41.57% | |

| 1996 | 5565 | 10890.1 | 51.10% | |

| 1997 | 4361.3 | 10030 | 43.48% | |

| 1998 | 5336.23 | 9169.2 | 58.20% | |

| 1999 | 5613.7 | 8308.3 | 67.57% | |

| 2000 | 2763.2 | 7448.4 | 37.10% | |

| 2001 | 2573.5 | 7448.4 | 34.55% | |

| 2002 | 3133.2 | 7448.4 | 42.07% | |

| 2003 | 2961.6 | 7448.4 | 39.76% | |

| 2004 | 2632.9 | 7448.4 | 35.35% | |

| 2005 | 1920.5 | 7448.4 | 25.78% | |

| 2006 | 1462 | 7448.4 | 19.63% | |

| 2007 | 849.9 | 7448.4 | 11.41% | |

| 2008 | 450.8 | 7448.4 | 6.05% | |

| 2009 | 376.4 | 7448.4 | 5.05% | |

| Source: World Trade Organization, Agriculture Information Management System, Export Subsidies Notifications. | ||||

EU negotiators already agreed in principle to eliminate export subsidies because they know unilateral policy reforms will do that eventually. EU export subsidies have not been close to 50 percent of their WTO ceiling since the late 1990s, but agreeing to lower the cap would mean giving up something for nothing. Personally I disagree that salvaging something meaningful from the Doha Round is nothing, but I’m not a trade negotiator. EU negotiators continue to insist that it will only agree to disciplines on its direct export subsidies if the deal includes other, indirect, or potential subsidies related to state trading enterprises and food aid.

The US performance is even more disappointing—and ill-suited to a country that claims to be a global leader. US Ambassador to the WTO Michael Punke is also playing the blame game, criticizing anyone that suggests a Bali package should go beyond trade facilitation (and maybe a narrow, technical issue related to administration of agricultural quotas). US negotiators do not want to add export competition measures or LDC issues to the Bali agenda because the United States would be squarely in the crosshairs over food aid, agricultural export credit guarantees, cotton subsidies, and duty-free, quota-free market access for LDCs.

US negotiators are on the defensive because the United States is the only rich country in the world that continues to provide almost all of its food aid in kind, and almost the only one that does not provide duty-free, quota-free market access for at least 98 percent of all products to LDCs (don’t get me started on whether Korea is a developed country or not!). US policymakers have made some progress on agricultural export credits, as a result of losing the WTO complaint brought by Brazil against US cotton subsidies (including excessive export credit guarantees). Also in response to the WTO case, the draft House and Senate farm bills would lower subsidies for cotton.

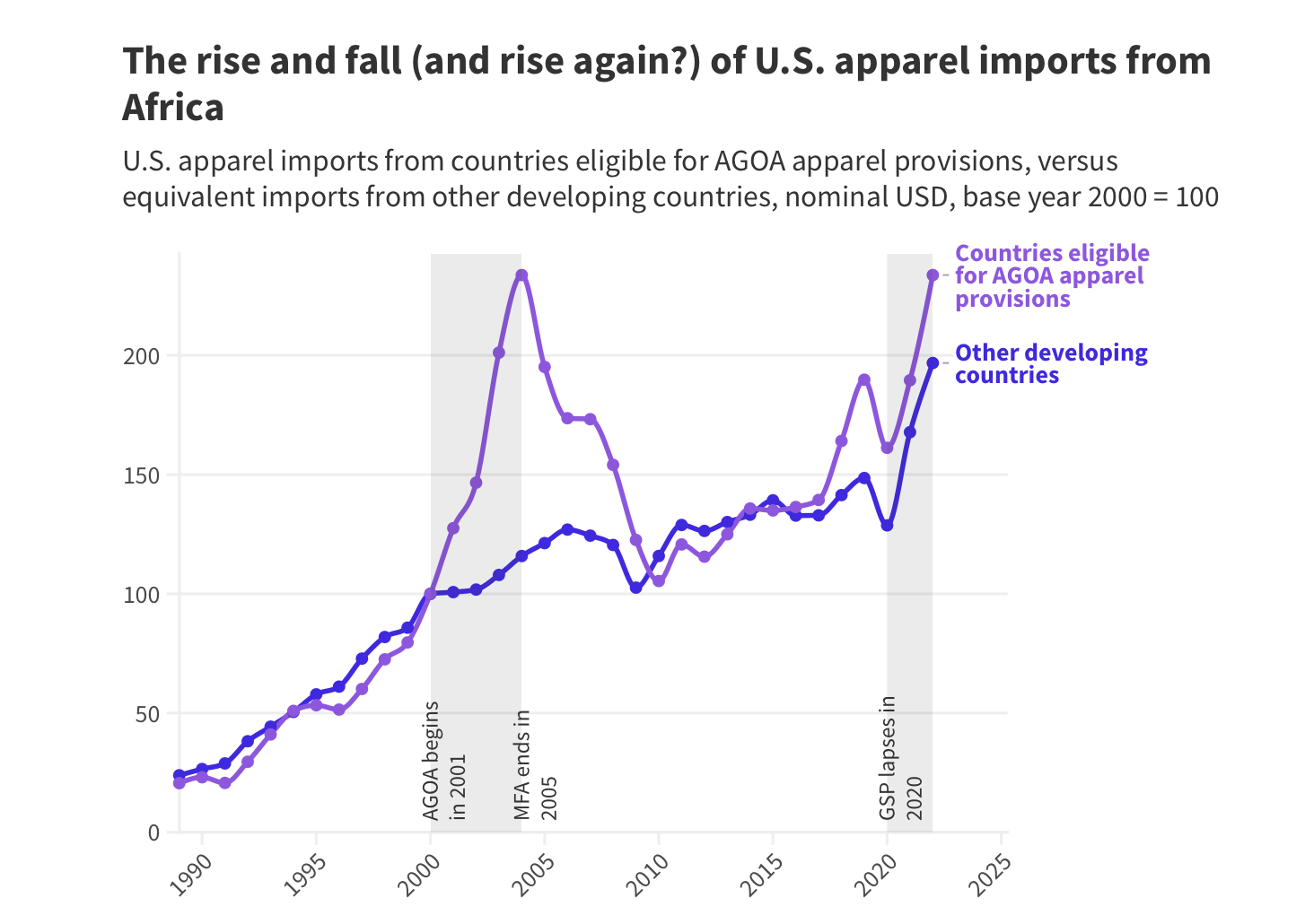

But I continue to be puzzled that is so hard for a country as large and rich as the United States to open its market to imports from the poorest and most vulnerable countries in the world. Countries that, collectively, account for just 1 percent of US imports. Some will say that now is not the time for this initiative because Bangladesh is one of the LDCs that would benefit. But why not use the promise of duty-free, quota-free market access as an incentive to encourage Bangladesh to significantly and sustainably improve working conditions in the garment sector and protect the jobs of 4 million young women? (As I said here, stop waiving the tiny twig of withdrawing GSP on 1 percent of Bangladesh’s exports—US GSP excludes clothing—and proffer the giant carrot.) And, by the way, use it to get a more positive outcome in Bali.

On food aid, the Obama administration and a bipartisan pair on the Hill are proposing to reform the current wasteful and inefficient approach as means to stretch an ever tighter budget a bit further. But that has not softened the opposition from US trade negotiators to addressing export competition issues as part of the WTO agenda. Nor have I heard anyone add to the arguments in favor of food aid reform that it could be used to leverage the elimination of the EU export subsidies, a long-standing US goal.

To recap, the following simple steps by key countries would contribute to improved budget situations in rich countries, improved development prospects in poorer ones, and a revitalized international trade system:

- US implementation of the duty-free, quota-free market access initiative for LDCs (1 percent of the total), leveraged to improve working conditions in Bangladesh

- US implementation of reforms of its in-kind food aid practices, which would also stretch the food aid budget to reach another 4 million to 10 million hungry people

- EU agreement to bind the elimination of exports subsidies (or at the very least accept the G20 proposal)

- India acceptance of a trade facilitation agreement, without conditions

Oh, and what about China? For a big country, they’ve been mighty hard to find during these negotiations. And the petty squabbling goes on.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.