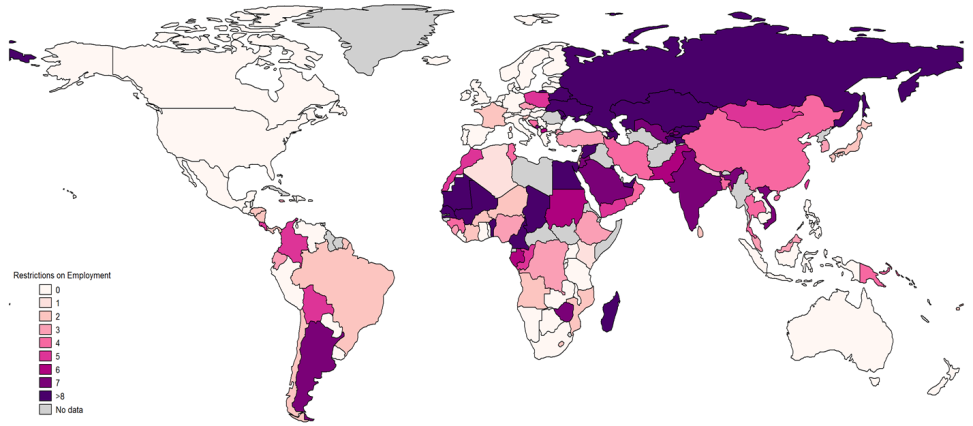

We noted in a previous blog that 79 countries restrict the type of jobs women can do just on the grounds of their sex. Fifteen countries, including Bolivia, Cameroon, Jordan, and Sudan also have laws on the books saying husbands may prevent their wives from accepting jobs. The figure below color codes countries on the number of restrictions they place on women’s employment from none to many. Unsurprisingly, countries that impose work hour or industry restrictions have lower female labor force participation rates (45 percent compared to 60 percent with no restrictions according to the 2012 WDR). And that only accounts for direct legal barriers to employment. Indirect barriers such as banning women from driving can have a dramatic impact on their ability to earn a living. Removing barriers to women’s economic opportunity depends on changing norms in women’s home countries, but there is a role for donors and others to play. We come to that below.

Figure: Laws against Women Working

Source: Authors’ map based on data from Women, Business and the Law

TV Guides

Because of the close link between norms about gender roles and laws governing those roles, one important factor behind improving women’s employment outcomes will be helping to shift the idea that a woman’s place is in the home. Television has proven a very effective tool to change attitudes about gender: as the signal for Brazil’s Rede Globo television channel spread across the country, carrying soap operas featuring strong independent women with few kids making good money, fertility declined and divorce rates climbed. There might be a role for donors to help local television and radio stations learn from experiences elsewhere of creating popular programming that carriers similar social cues. South Africa’s Soul City Institute is a prime example.

Trade and Investment

Beyond aid, there is an opportunity to use trade and investment policy to further gender equality in economic opportunity. US bilateral trade and investment treaties frequently contain language about labor laws and working conditions. It is standard language in US bilateral investment treaties that neither party shall weaken labor standards in an effort to attract investment. In addition, there is standard language freeing covered enterprises to employ senior management of any nationality they chose. In some trade pacts there is specific mention of gender issues. The Peru Free Trade Pact, for instance, includes a labor cooperation and capacity building mechanism for “developing and pursuing bilateral or regional cooperation activities on labor issues, which may include, but need not be limited to: …. development of programs on gender issues, including the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.”

More in This Series

In future bilateral and plurilateral trade and investment treaties, US negotiators could routinely include support for bilateral or regional cooperation activities regarding the elimination of discrimination. In addition, future trade and investment treaties could also mandate that “neither party may require that an enterprise of that party that is a covered investment deny employment on the grounds of race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation.”

Preemptive Contract Action

Another approach might be to build on CGD’s model for odious debt, using it to highlight countries where women’s abilities to contract on an equal basis with men is circumscribed. For instance, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo a woman must relinquish legal capacity once she is married and is required to obtain her husband’s consent before signing contracts or executing legal acts. Under the original odious-debt proposal, countries declare that any new contracts signed with a particular regime (as it might be, Syria’s government) would be unenforceable in their courts. In the case of contracts that are odious on the grounds of gender discrimination, the United States and other governments might declare that, going forward, contracts that effectively discriminate against the economic interests of a woman because of their legally inferior status in contract law would be unenforceable in the courts of countries signing onto the declaration.

Refugee Status

Finally, governments could use the signaling power of refugee status to highlight countries where economic discrimination on the grounds of gender is so extreme as to constitute a serious rights violation. Building on the Guatemala decision described in a previous post the US attorney general could issue regulations on the subject of membership in a particular social grouping made up of women significantly discriminated against due to legal restraints on their economic activity that form part of the basis for determining refugee status. A new attorney general could issue regulations to clarify that women from countries where the right to free movement or employment is expressly and egregiously limited by law form part of a particular social grouping potentially eligible for refugee status. Asylum seekers who have attempted to exercise that right and been prevented under the auspices of the law would have potential eligibility for asylum.

Over the next two years, we’ll further explore the rationale, practicality and impact of these ideas. And we’d love any thoughts in the comments below that could help shape — or shoot down — some of the proposals.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.