How schools are managed––things like budgets, staffing, and planning––matters for school effectiveness and children’s learning. But how easy is it to improve this (at scale) in poor countries? In a new CGD working paper we evaluate the impact of a large-scale school leader training programme implemented across hundreds of primary schools in Rwanda in 2018 - 2019. The programme, implemented by the Rwanda Education Board and Belgian NGO VVOB aimed to enhance headteachers' skills in leadership, management, and teacher support, with the goal of improving student learning outcomes. 240 schools took part in 2018 and 2019, and overall, staff at nearly all 2,500 public schools in Rwanda have received similar training.

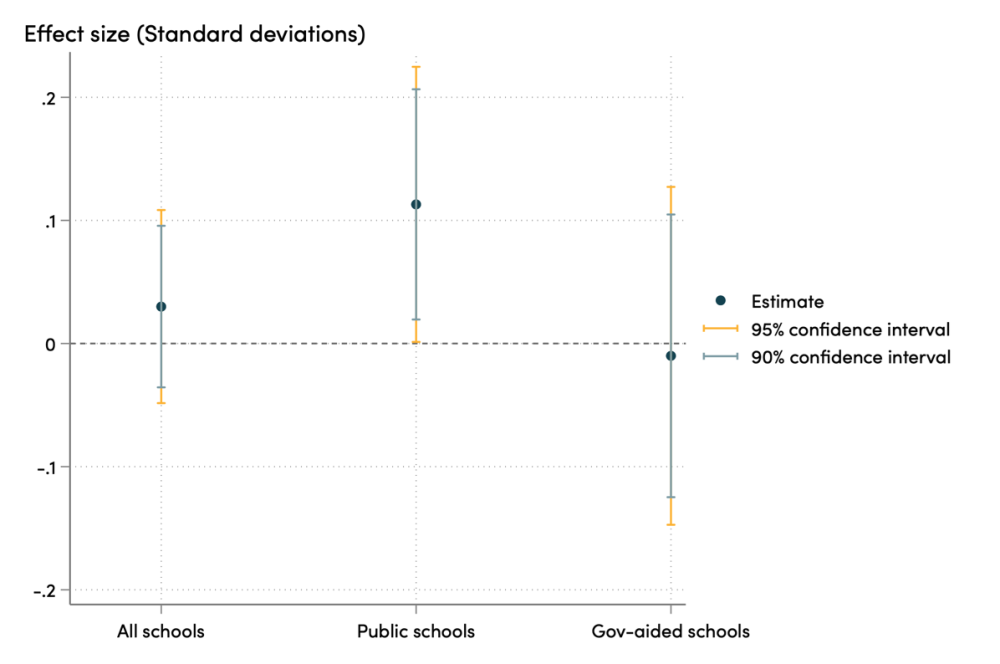

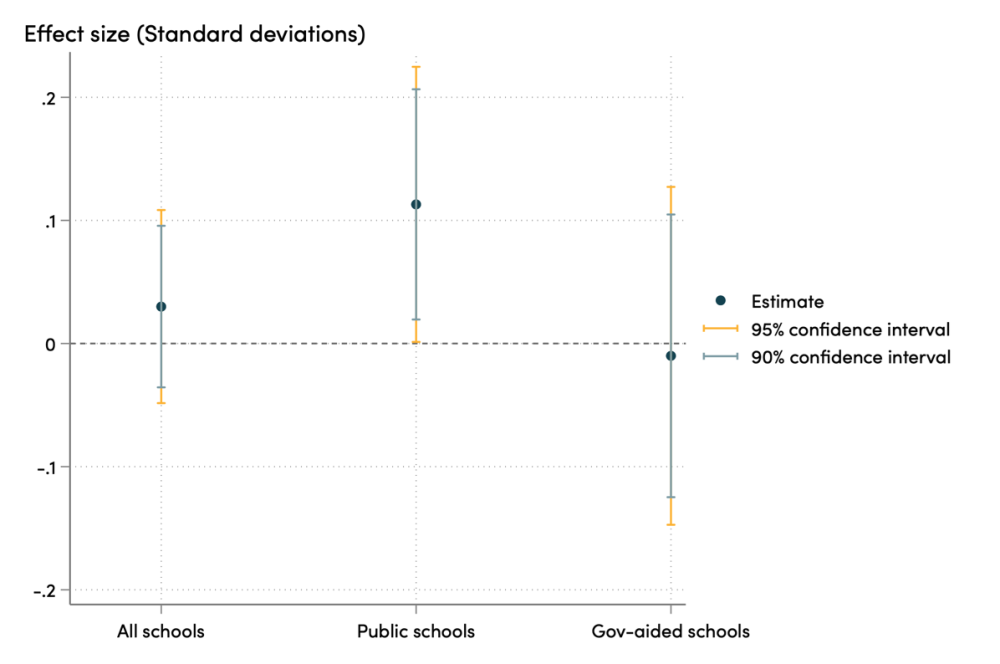

We find that one to two years after the intervention, there is a small and statistically insignificant average improvement in student test scores. When we break it down by type of school, we see an improvement for regular public schools (0.11 standard deviations), whereas there is no effect in government-aided schools (typically church-owned schools with slightly above average performance). It seems plausible to us that this disparity may be explained by weaker prior management and resources in public schools, as well as time constraints and more rigid governance structures for headteachers in government-aided schools (though his heterogeneity analysis is not pre-specified so take it with a grain of salt). We also see some tentative signs that effects are larger for schools in poorer and more rural areas–consistent with the idea of effects being biggest for the least well-prepared schools.

Figure 1. Effect of school leader training on student test scores

As noted in a prior CGD systematic review, modest learning gains can still translate to substantial cost-effectiveness when you are only training one person (the headteacher) and impacting hundreds of children in a school. The total cost of the programme was $1,412 per headteacher. Whilst we only have test score data on learning for children in grade 6, it’s reasonable to expect that the effect of learning should be similar for children in other grades. Considering the total cost of training all the headteachers (in public and government-aided schools), and a 0.1 standard deviation benefit for the roughly 850 children in each of the public schools, leads us to a total gain of around 2.5 standard deviations per $100 spent–falling roughly in the middle of the range of cost-effectiveness of education interventions reviewed by Kremer et al (2013).

Our study was limited to looking at test scores, as this was all the data that was available. There’s good reason to think that school management matters for children’s wellbeing as much as their learning. We also weren’t able to look quantitatively at exactly what changes in the practices of managers and teachers actually occurred, but qualitative interviews did suggest some increase in attention paid by leaders to supporting new teachers. Further research might focus on understanding the most effective ways of designing and delivering school leader training. As Rwanda continues implementing this programme nationwide, a focus on public schools and rural areas may provide the highest returns on investment.

Our study contributes to the growing evidence base on the importance of school leadership in improving educational outcomes, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Even modest gains can be cost-effective when programs are tailored to specific contexts and target the most disadvantaged schools.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.