Under the Obama administration, US funding for family planning has grown significantly; in 2015, US bilateral disbursements totaled about $638 million, representing 47.5 percent of total bilateral disbursements. The increased investment has been good news for women, girls, and their families; access to contraception helps prevent millions of unintended pregnancies, reduce maternal and infant mortality, and empower girls to avoid adolescent pregnancies and invest in their educations and future careers. But a new administration could mean new priorities at home and abroad—and funding for family planning may be particularly at risk. The family planning community still has time to make the case for sustained US funding, protecting the gains that it has already achieved. But smart advocacy should also be accompanied by contingency planning—what would it mean for the United States (US) to substantially cut its contribution?

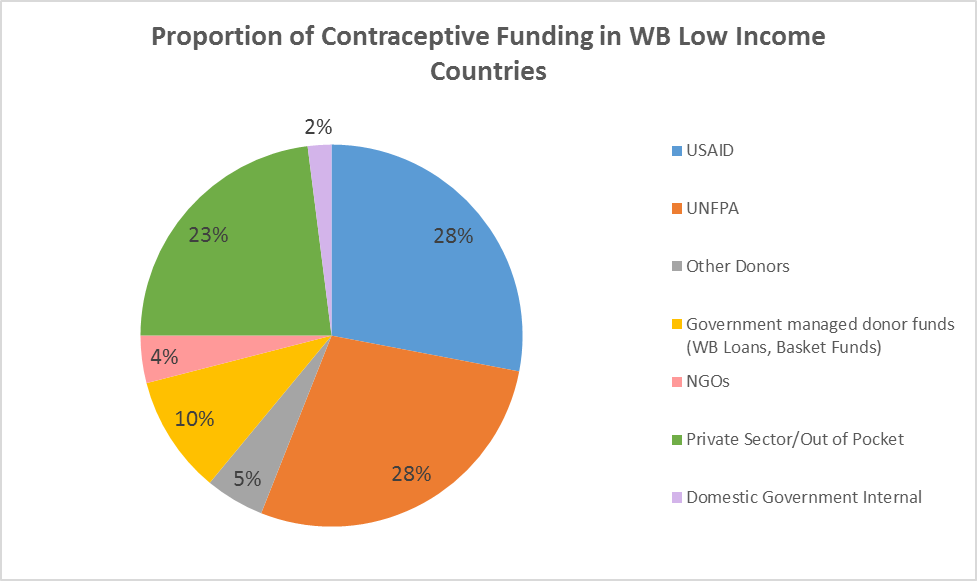

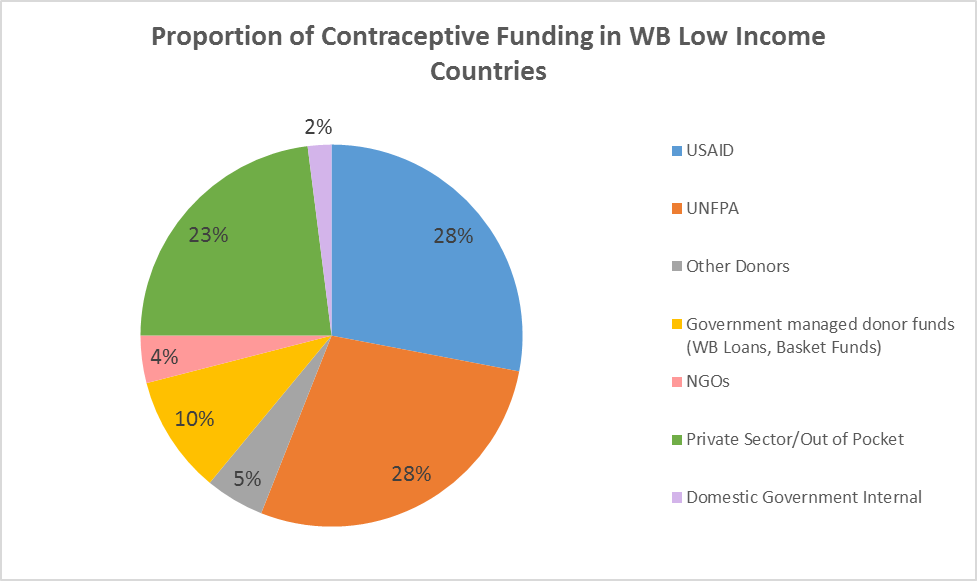

Consider this: right now, in low-income countries (LICs), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) contributes about 28 percent of all funding available for contraceptive commodities. (That proportion grows substantially, to 36 percent, if you exclude private out-of-pocket spending.) According to data provided by FP2020 (on request), there are currently about 36 million users of modern contraception in LICs. With some back of the envelope math (and assuming cost per contraceptive user is uniform across different funding sources), that means that about 10 million women and girls in low-income countries currently rely on USAID funding for their contraceptive commodities. And the effects of US funding cuts would extend far beyond USAID’s commodity supply chains; the US is also the largest funder of direct family planning service delivery, and US funds support other contraceptive suppliers like UNFPA and the World Bank.

Source: Estimate compiled by USAID, based on Avenir Health data and Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition (2016). Global Contraceptive Commodity Gap Analysis.

How would low-income countries respond to such a shock? Well—with great difficulty. Government expenditure in LICs barely even registers on the chart; note the tiny purple sliver at the top (just 2 percent!). Realistically, most LIC governments would not be able to fill a funding gap generated by USAID cuts. Private funding—mostly women’s out-of-pocket payments—already accounts for 23 percent of the total; without government funding to fill the gap, that proportion would likely rise, drawing from scarce household budgets. Meanwhile, the overall donor landscape for family planning financing looks shaky. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, total donor funding fell 6 percent in 2015 even as the US contribution held steady. The main culprit: an appreciating US dollar that has reduced the real purchasing power of non-US donor governments.

In this context, the family planning community needs a contingency plan to ensure continuity of services for existing users in the face of hypothetical US cuts. Funders should ask themselves two questions:

- Can I increase funding for family planning to help fill a gap—and by how much? In this scenario, UK leadership will become even more essential. In 2012, the UK helped reignite the global family planning movement through its leading role in the creation of FP2020; in 2017, DFID may need to act again to maintain existing momentum. And now would be a great time for other donors to increase their investments—could Canada, Japan, South Korea, or private foundations step up with some new money?

- If necessary, which existing funds can be reallocated to ensure continuity of services? Doing so would likely entail difficult trade-offs—for example, redirecting advocacy or behavior change funds toward commodities and direct service delivery—that might compromise long-term efforts to expand access. Yet the human cost of forced discontinuation is unacceptable. And pulling the rug out from women and girls who currently rely on contraceptives will generate enormous distrust among the populations that FP2020 is trying to reach, potentially causing irreversible damage to family planning efforts.

Beyond any immediate fears, the current situation also illustrates the big-picture danger of donor dependency. Donor funding, especially for contentious issue areas like family planning, is highly vulnerable to shifting domestic priorities. Low- and middle-income countries will need to increase their domestic expenditure on family planning to weather donor shocks; a government expenditure share of just 2 percent simply won’t be viable in the long-run. That means donors should accelerate and expand existing efforts to create better incentives for government co-financing—an issue we highlight in our recent working group report on the FP2020 partnership.

The bottom line for the FP2020 partnership: it’s time to hope (and work!) for the best—but plan for the worst.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.