Journalists have warned you that there are now 60 million refugees worldwide, and that Europe faces “the worst refugee crisis since World War II.” They’ve told you this again and again and again and again.

Well, fact check: It’s not true. Not even close.

First, most of the people displaced by violence, like the slow catastrophe in Syria, are not properly called refugees because most of them have not left their country. Second, Europe’s current refugee crisis is certainly not the most serious since World War II. The international community has handled much more, and they’ve done so recently. If Europe is unable to accommodate the current influx of people fleeing violence, it’s because of a failure of policies and institutions, not because of unprecedented numbers.

The Real Numbers

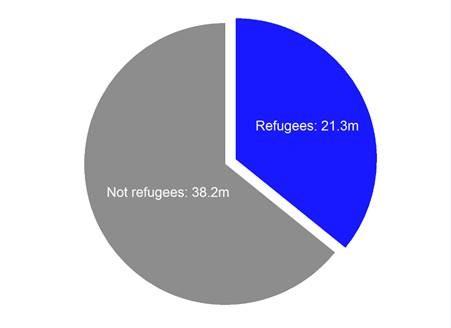

That 60 million number comes from the United Nations, and it has really taken on a life of its own. But the UN is referring to the total number of people forcibly displaced from their homes. The large majority of those displaced people, despite the horrors many of them face, don’t leave their own countries. Only people who are forcibly displaced to other countries are defined as refugees. Here is the breakdown of those 60 million forcibly displaced people, from 2014:

That is, the large majority of forcibly displaced people have not shown up on rich countries’ doorsteps. By the UN definition, they are not refugees. Last year there were 21 million refugees in the world.

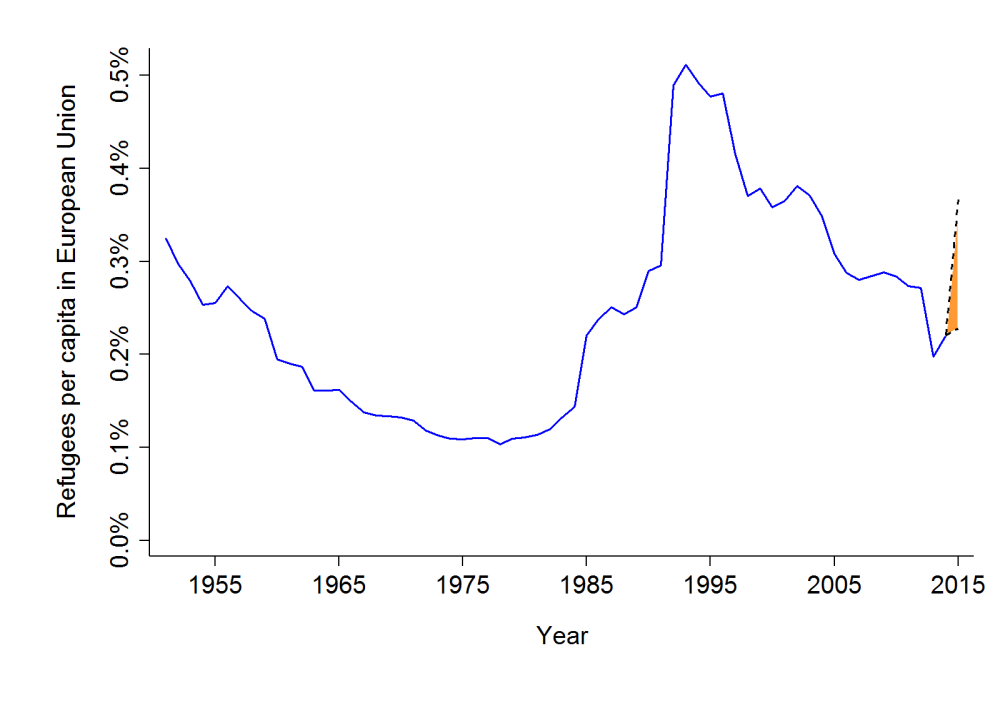

And despite the shocking images in the press, the numbers of refugees do not come close to making this Europe’s biggest refugee crisis since World War II. Here are the real UN numbers on refugees in Europe, 1951–2014, plus a range that includes all plausible scenarios for 2015:

The blue line is the actual number of all refugees in the countries of today’s 28 European Union member states, through 2014. The orange area is a range of numbers that we’re likely to see by the end of 2015, from the lowest plausible to the highest plausible. That range depends not just on how many people show up in Europe claiming asylum, but how many are actually granted refugee status and benefits.

You can see in that figure that Europe as a whole can do and has done much more than it is now. In the mid-1990s, Europe was successfully hosting refugees to the tune of 0.5 percent of its population. In 2014, that number was much lower, just over 0.2 percent. Even with the surge of pressure this year, the numbers are very unlikely to reach the levels seen just 20 years back.

Individual European countries have handled much, much more than even the highest regional average. After the Hungarian revolution of 1956, Austria found itself with 2 percent of its population as refugees. That’s four times the highest level you see in the figure above. And that was at a time that Austria itself was still wrecked by war.

None of this is to diminish the challenges Europe currently faces. There is certainly a major crisis in the policies and institutions designed to receive, process, and assist people who arrive seeking refugee status.

Those institutions are overwhelmed because Europe and the world community have not decided how to share the responsibility to protect these people. But Europe itself, both its economy and its society, are nowhere close to being overwhelmed. As Oxford’s Alexander Betts succinctly puts it, this refugee crisis “isn’t necessarily a crisis of numbers, it’s been a crisis of politics.”

The answer, too, lies in politics: stronger institutions to encourage cooperation and greater receiving capacity. These flows are not a major departure from other recent flows into the region when considered in larger context. The EU has admitted approximately 3.5 million long-term immigrants each year since 2010. Assuming asylum applications continue on the same scale for the rest of 2015, the EU will receive approximately 720,000 petitions this year. Even if all petitions were somehow approved (which is impossible), this would represent only an approximately 20 percent increase over current inflows.

The cooperative infrastructure to handle that increase can and must be built, and should extend beyond Europe to the United States and other countries who long ago promised to protect refugees. Refugees are not drowning us, but inaction could.

———

The raw data for the figures above, and the calculation of the ‘high’ scenario are available here. The ‘high’ scenario is estimated as follows: We take the Frontex estimates of illegal crossings into Europe for the first two quarters of 2015, and take the ratio of these to the numbers for the first two quarters of 2014. Multiplying this ratio by the 2014 third-quarter figure gives an estimate for the 2015 third-quarter figure of about 300,000. This roughly agrees with the Frontex figure for July 2015, the first month of the third quarter: 107,500. We then sum these projected numbers for 2015: 720,187. To be conservative, we double that number to 1.44 million. To be even more conservative, we assume that all 1.44 million people apply for asylum. To be furthermore conservative, we assume that 50 percent of those applicants will be accepted as refugees (the current acceptance rate is just 4.1 percent, from Eurostat). This results in an implausibly high projection for the increase in refugees in Europe during 2015: 720,187. This is much higher than any public estimate of approved refugees for 2015 (not asylum-seekers) made by the UN or the EU. The ‘low’ scenario for EU refugees in 2015 is calculated from the 2015 average of new asylum applications to date (62,466 per month) and a 5 percent acceptance rate — slightly higher than 2014’s 4.1 percent (Eurostat).

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.