The long-awaited European Commission Communication on the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2021-2027—the EU’s long-term budget—has been unveiled, and so begins the EU’s big battle over money and priorities. Brace yourselves for a long arduous struggle that will expose divisions in the bloc in all sorts of ways—payers vs. recipients, east vs. west, north vs. south, federalists vs. intergovernmentalists, values vs interests. This is also the review that will shape the future of EU development cooperation and the credibility of the EU as a major player in the international development sphere. Does the Commission’s proposal live up to the challenge?

Doing more with less—or with more?

The European Commission has billed the next budget as “doing more with less” although the figures paint more of a “doing more with more” picture and with one less contributor. The next EU budget as proposed by the Commission has not only filled the giant hole left by Brexit (€13 billion per year) but has built a small hill over it too. And development aid emerges as one of the winners with the EU retaining its market share as the fourth largest bilateral aid donor in the world (following the US, Germany, and the UK), at least in this proposal. However, experience from the last MFF rounds shows that as the negotiations progress with the many compromises and concessions, it is development that suffers disproportionately from other competing agendas.

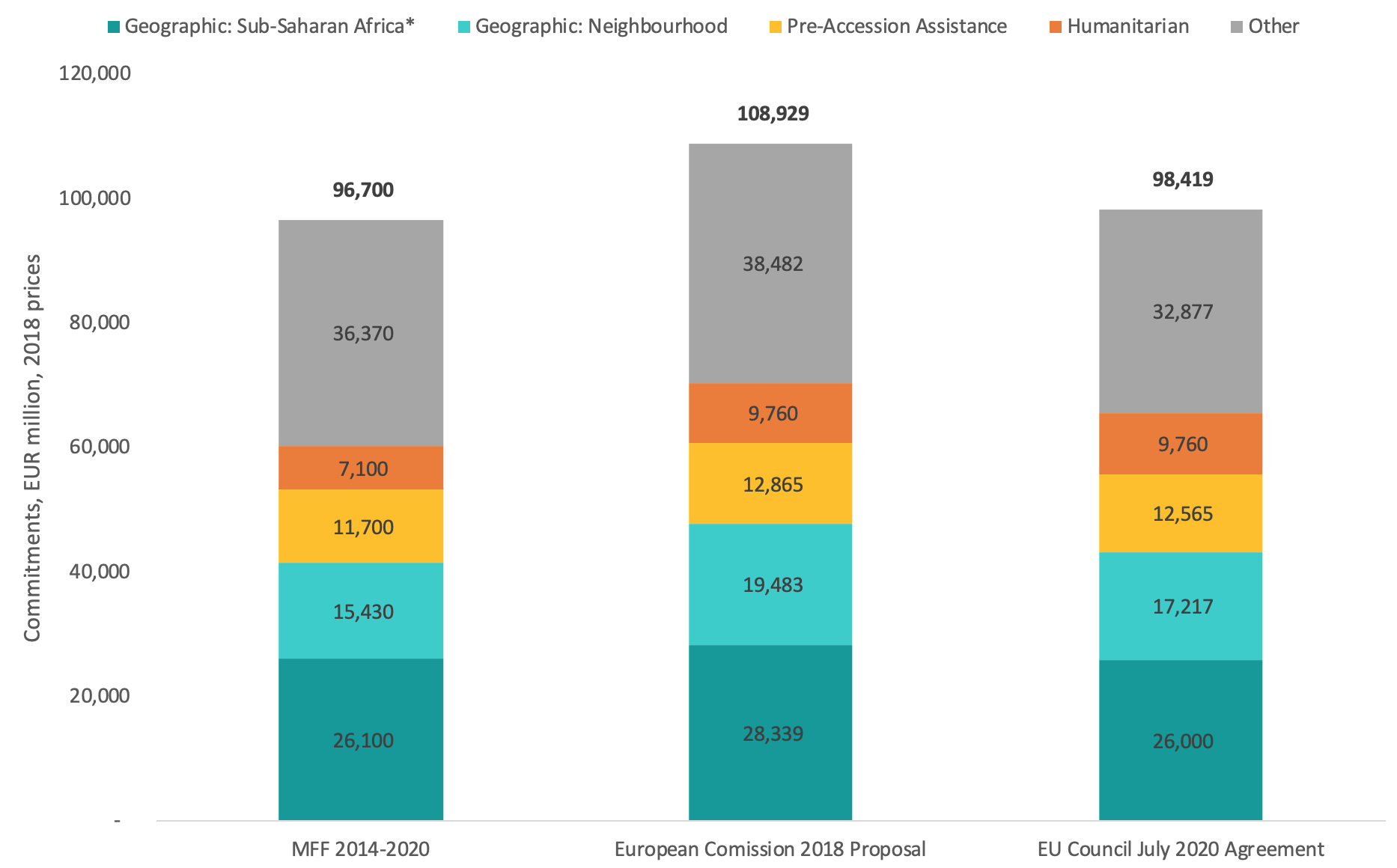

This is the first batch of proposals setting out the overall budgetary principles, structure, and expenditure ceilings. The legislative proposals for sectoral spending will come out on June 14. At first glance, things are looking up for EU development spending with a proposed 26 percent increase from €97 billion (including the off-budget European Development Fund) to €123 billion over the seven-year period, and an increased share of the EU budget from 6 percent to 10 percent. All this without the UK’s current annual contribution of €1.4 billion to EU development spending. The increase comes from a variety of measures, including the scrapping of budget rebates and a reduction in agricultural subsidies and cohesion funds. To date, roughly 75 percent of EU spending has gone towards just two policy areas: direct payments to producers under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and to the Cohesion Policy which focuses on the development of regions inside the EU. The new budget proposes that the share of CAP and Cohesion Policy is reduced by around 10 percent.

The budget is based on a set of principles including a stronger sense of European value-ad—in particular in addressing issues that transcend national borders—i.e., global and regional public goods; rationalisation with a reduction in the number of financial instruments and programmes by more than a third; and greater flexibility within and between programmes to move money around and the creation of reserves to tackle unforeseen events and crises.

Three Big Changes to Unpack

Translating these principles into external action spending, the Commission has proposed three big changes to what was once “Heading 4: Global Europe” with implications for the future of European development cooperation:

-

Global Europe has now become “Heading 6: The Neighbourhood and the World,” giving prominence to promoting security, stability, and development in the EU’s troubled neighbourhood. This is a clear geographic expression of where the EU’s see its real value add. A large share of EU ODA already goes to middle income countries (MICs) in the EU’s neighbourhood. From 2014-2016, the EU’s top recipients of aid were Turkey, Morocco, Serbia, and Tunisia. This is unlikely to change. Furthermore, the off-budget European Development Fund (EDF) will now be integrated into the EU budget. The EDF is the EU’s main aid instrument in low income Countries (LICs), targeting the 79 countries in Africa (of which 48 are in sub-Saharan Africa), and the Caribbean and the Pacific. With its integration into the budget, and the primacy given to the EU’s neighbourhood, there is a real risk of weakening not only the financial commitment towards these countries, but also their privileged relationship with the EU.

-

The number of financial instruments has been drastically cut, from the current 11 to 4. Most, including the EDF, have been merged into a single instrument, “the neighbourhood and international cooperation instrument,” covering a geographic pillar focused mainly on the neighbourhood and Africa, a thematic pillar addressing global issues, a rapid response pillar for crisis management and conflict prevention, and a new investment architecture to crowd in additional resources building on the European External Investment Plan. Humanitarian aid, pre-accession, and the Common Foreign and Security Policy will continue to have separate financial instruments. This is an interesting construct which attempts to untangle the hybrid constellations of geographic and thematic cooperation and reconcile a values-based rationale for development with an interests-based one. This is similar to the proposal put forward in a paper I co-authored with the European Think Tanks Group. In that paper, we suggested that external actions funds should be managed through three instruments: 1) a geographic instrument in support of national development problems emphasising national priorities; 2) a thematic instrument for global sustainable development supporting global development problems which require collective action and the promotion of mutual interests; and 3) an instrument incorporating the European Fund for Sustainable Development to crowd in additional resources deploying blended finance.

-

Flexibility is written all over this budget with a cushion of unallocated funds in the neighbourhood and international cooperation instrument mainly to address “emerging challenges and priorities,” and an additional unallocated margin of around 4 percent of the external actions budget. Furthermore, the current flexibility of the EDF which allows un-committed funds to carry over and the re-use of de-committed amounts has been incorporated into the EU budget instruments. Flexibility, however, also comes with risks, such as skewing incentives and responding more to EU political priorities than to the partner country context and needs.

Much still left to be decided

The Commission’s blueprint for external action spending leaves many unanswered questions. These include the geographical allocation of funds and the criteria on which it will be based; the application of the principle of differentiation; the EU’s thematic priorities; the management of the instruments across the European Commission’s Directorates-General and the responsibility for them amongst Commissioners; the management of unallocated funds, in particular for emerging priorities; and the ODA-eligibility of the instruments.

More detail will be forthcoming in mid-June with the Commission’s legislative proposals. In the meantime, however, the battle has begun on the overall size of the EU budget and the distribution of funds across EU priorities with the next European Council (Heads of State) meeting on June 28 and 29 as a key milestone. It is at that meeting that stakes will be put in the ground and “red lines” drawn, which will give us an indication of which way the wind is blowing for development. This will be followed by a long inter-institutional match between the Member States and the European Parliament, taking us into 2019 past the European Parliament elections and the appointment of the new European Commission. This battle will be about the legislative proposals where structure, programmes, instruments, benchmarks, rules, and regulations are all up for grabs.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.