Agricultural subsidies are almost a complete waste of money, go to the wealthiest in society, and are also damaging to global development. With a Green Paper expected on agriculture in the coming weeks, how can the UK do better after Brexit?

What does the tax-payer spend on agriculture subsidies?

The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) spends major amounts subsidising farmers. This expenditure accounts for some 40 percent of the EU’s budget (some €60bn per year, a cost of some €118 euros a year for each of the EU’s 508m citizens). This excludes the effect of EU trade protection on food prices which the OECD calculate earns farmers a further €20bn per year.

In the UK, agriculture subsidy is some £3.1bn per year (again excluding trade effects). Of the infamous £350m per week that goes to the EU (it’s actually £250m after the UK’s rebate), some £60m comes back as agriculture spend. Subsidies were equivalent to 12.5 percent of the total UK agricultural output in 2015.[1]

Who does it go to?

The major beneficiaries of subsidy are land-owners. The vast majority of this agricultural spend is in the form of “direct payments.” These payments, originally introduced 25 years ago as compensation for the removal of minimum prices, are now based on land area. Beneficiaries include the Queen, Prince Philip, and a billionaire Saudi prince who receive large sums alongside farmers and land-owing conservation charities like the National Trust. Other non-farming landowners also benefit as subsidies to tenant farmers increase rents on the land (at the EU level this effect has been estimated as adding potentially 30 percent to land values).[2] In the last reform, direct payments were made conditional on ‘Greening’ by farmers—but the additional environmental value has been limited.[3]

A minority of the subsidy directly benefits the environment (though other subsidies, for example tax breaks for fuel used on farms, damage it). In the UK some £0.6bn—around 20 percent—is for environmental and rural development grants which are recognised as delivering significant environmental benefits. This funding plays an important role in the UK’s environment, though could achieve even more if it was more directly targeted on enhancements to ‘natural capital.’

How does subsidy influence UK competitiveness, prices, and food security?

Without subsidy, the UK agriculture sector is likely to be smaller but more competitive and more productive. Even though (most) EU farm payments are not paid according to the quantity of certain products, they do still depend on the beneficiary being an active farmer. So, without subsidy, some farmers (and perhaps their land) would move out of agriculture. The effects would need to be assessed but are likely to (marginally) reduce UK agricultural output (and increase output in other sectors).

UK food prices are unlikely to be materially affected. Basic industrial economics suggests reduced subsidies lead to increased prices, however, for a small producer like the UK, food commodity prices are largely determined by international markets. This means UK trade arrangements will matter to food prices (for example, see the Government’s pre-referendum analysis showing retail food prices could rise by almost three percent in a very hard Brexit), but subsidies have very little effect.

UK food security does not depend on subsidy. Whilst reduced subsidy could reduce the proportion of UK food supply produced domestically (referred to as “self-sufficiency”[4]) small changes in this indicator are irrelevant to whether the UK could feed itself in a crisis where sound trading and domestic transport links are much more important, as set out systematically in the UK Government’s comprehensive Food Security Assessment in 2010.

What about developmental impacts of UK agriculture?

The UK’s approach to agricultural subsidies won’t directly impact global prices or development but it will influence the direction of reforms in the EU and World Trade Organisation that will.

Wealthy countries’ approach to agricultural policy (especially on trade) is still important to the prospects of developing countries (my colleague Kimberly Ann Elliott is releasing a book on just this in spring!). Agriculture accounted for 18 percent of all economic output in each of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa in 2015. No country ever got rich without trading and if developed countries like the UK subsidise their industries, this creates an uneven playing field, hindering development. Still, the UK only accounts for a small proportion of global agricultural output (even in wheat, UK exports are just 1.7 percent of the global total) so global agricultural prices would not be materially affected.

The UK’s choices will influence wider reform efforts. First, the EU will soon be considering its own approach to agriculture for the period 2021-2026 and along with a circa 15 percent Brexit drop in its budget the UK’s approach may encourage (or discourage) reform-minded actors. Second, agricultural subsidies have grown significantly in some emerging economies[5]and this huge global game of prisoners’ dilemma is crying out for the countries to agree a much-lower global ceiling on agricultural subsidy. If the UK joined Australia and New Zealand in eliminating subsidies, it would mark a major shift at the World Trade Organisation.

UK Government choices

The Government has guaranteed existing subsidies until 2020. After that, the UK can choose its model for agriculture. So far, the Government has said it is exploring US/Canadian insurance-based subsidies which are distortionary and administratively expensive, but can at least reduce subsidy levels. The centre-right Times newspaper and the Chair of Theresa May’s Policy Board have made some encouraging noises about reforming agricultural subsidies.

After 2020, the UK should reduce subsidy to under £1bn within five years and use it to reward the provision of public goods. This would save over £2bn per year (£40m a week for the NHS) and align with WTO proposals of the reform-minded Cairns Group[6] to limit subsidies to 5 percent of agricultural production. The five-year transitional arrangement would enable planning in the sector, and if there are impacts on jobs, then support (perhaps substantial given the small number affected) should be focused on funding training or compensating workers who are actually affected, rather than on the continuing to support the sector.

Agricultural subsidies are large, wasteful, and highly regressive. Some argue the political realities of vested interests mean that Government is effectively unable to take the control that Brexit implies. The UK Government has long-called for subsidy reform in the EU, it should ensure that the opportunity doesn’t pass it by.

[1]The UK produced £23.9bn in 2015. Agriculture in the UK

[3] “The early evidence from these decisions is that opportunities for delivering significant additional environmental value through the greening measures have not been taken in most cases.” Learning the Lessons of the Greening of the CAP

[4] In 2015 this was 61 percent in all food, or 76 percent in indigenous food types. Table 14.1. Agriculture in the UK

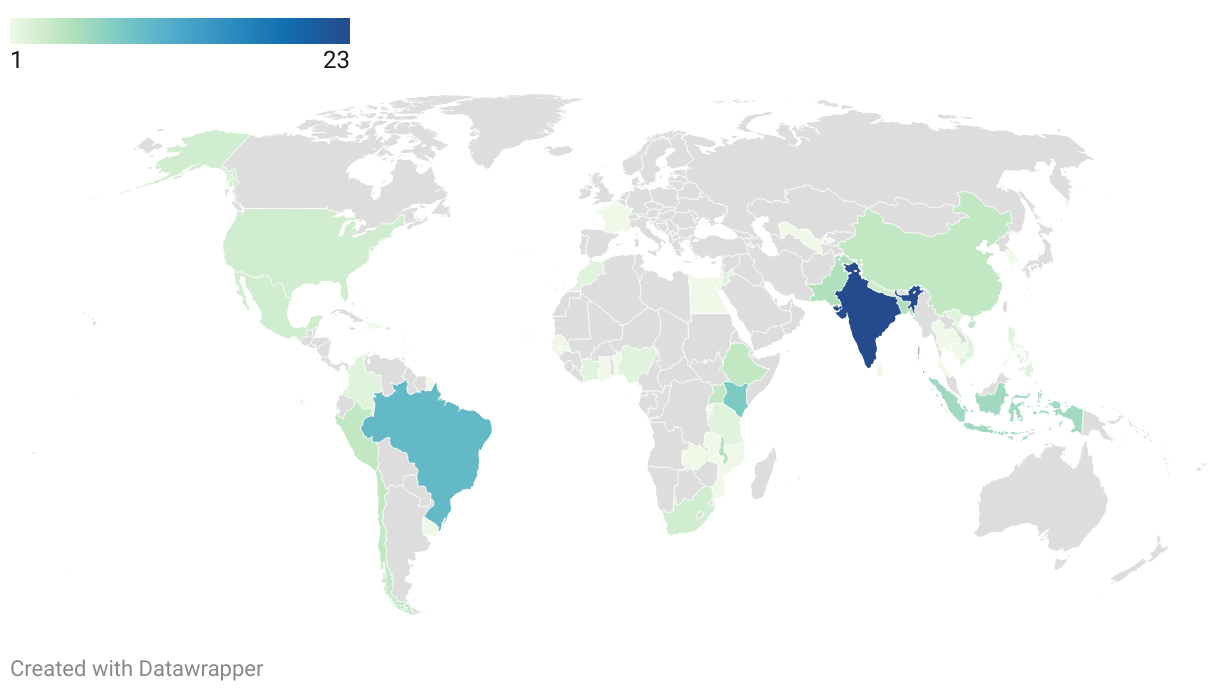

[5] Support to agricultural producers averaged over eight emerging economies tracked by the OECD has risen to over 15 percent of farm receipts from under 5 percent before 1999—the increases are driven by China but also seen in Brazil, Indonesia and Kazakhstan. These outweighed decreases in the Colombia, Russian Federation and South Africa. Ukraine’s agricultural support remained very minimal. Figure 1.6 and 1.10. Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015

[6] Glauber, J. 2016. “Unfinished Business in Agricultural Trade Liberalisation”. November 2016

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.