This blog is the second in a series on the effects of Basel III on Emerging Markets and Developing Economies(EMDEs). The first one can be accessed here.

Just as Basel III, among other factors, played a role in the decline in the volume of cross-border lending from advanced economies to EMDEs, it created incentives for a shift in the composition of these flows. Banks’ exposures to certain business lines have been affected, including those that are crucial for development like trade finance and infrastructure finance (the latter will be the subject of a future blog). In this blog post, we briefly review recent trends in trade finance, and focus on the disincentives that certain components of Basel III have generated for banks engaged in this market.

Trends in Trade Finance

Trade finance products offered by banks (international and domestic) support countries’ export and import activities through the provision of liquidity and insurance against the risks involved in international trade. (Inter-firm credit between exporters and importers is an alternative form to fund trade activities.)

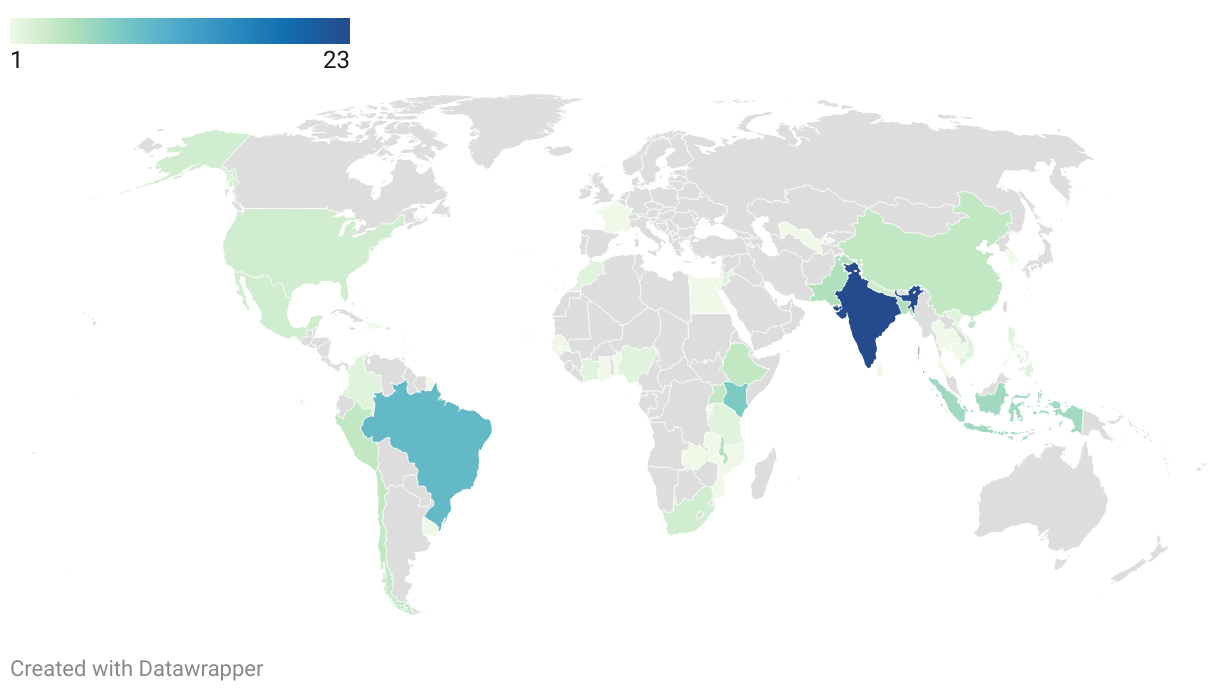

Since no comprehensive source of data on global trade finance exists—a theme we will come back to—indicators of this market’s evolution are taken from national sources and bank-level surveys and databases. For example, using data from 515 banks and 1,336 firms from 103 countries, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated a global trade finance gap of $1.5 trillion USD in 2016, with developing Asia accounting for the largest share.

To the best of our knowledge, the Committee on the Global Financial System’s 2014 report remains the most complete assessment of the size, structure, and recent developments of the global trade finance market. To explore the latest trends, we updated its series on the United States’ stock of bank-intermediated, short-term trade finance (including funded loans and unfunded off-balance sheet commitments and guarantees) vis-à-vis emerging markets and developing economics (EMDEs).

Chart 1 shows that in recent years there has been a declining trend in cross-border trade finance, although this trend began only in 2013 (there was a recovery in the post-crisis period). The decline affected both middle- and low-income EMDEs (Chart 1a). European banks have also reduced their funding for trade finance to emerging markets. Although some emerging markets’ domestic banks have, at least partially, offset global banks’ activities in this area, the overall capacity of the former tend to be smaller than that of the latter.

Chart 1: US Cross-Border Trade Finance to EMDEs (USD Billions)

Chart 1a: US Cross-Border Trade Finance to EMDEs by income categories (USD Billions)

Available data suggest that cross-border trade finance has not significantly recovered despite the recent pick-up in global trade. The rate of growth of world merchandise trade volume increased from 1.8 percent in 2016 to 4.7 percent in 2017 and is forecasted to reach up to 5.5 percent in 2018, although rising protectionist threats could significantly diminish this figure. For EMDEs, the rate of growth of export volumes more than doubled in the 2016-17 period, increasing from 2.6 percent in 2016 to 6.4 percent in 2017, with a forecast of 5.1 for 2018. Expectations for a recovery of cross-border trade finance rest on further improvements in global trade and completion of resolution of banking problems in advanced economies, especially European ones. However, some regulatory restrictions from the Basel III recommendations might be in the way of this recovery. For example, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) 2017 trade register reports that around 70-80 percent of its survey respondents (25 trade finance and export finance banks) agree or strongly agree that AML and KYC requirements and Basel III regulations are barriers to the provision of trade finance.

Basel III and Trade Finance

Under the Basel III framework, banks’ capital requirements are calculated by dividing regulatory capital by the amount of risk-weighted assets (regulatory capital consists of Common Equity Tier 1, Additional Tier 1, and Tier 2 capital; it absorbs losses in a way that reduces the likelihood of a bank failing and the impact if it does). The major risk components in the calculation of risk-weighted assets (RWA) are credit risk, market risk, and operational risk. Taken together, banks’ assets, weighted by these components, form the RWA (since different assets have different risk characteristics, a risk weight is assigned to each type of asset).

There are two alternative ways for banks to estimate credit risk, and therefore, RWA. The first is the standardized approach (SA), where country supervisors set the risk weights a priori that individual banks assign to their exposures. The second is the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach, where, under certain conditions, banks can use their own internal models to estimate credit risk.

Global banks use the second approach. However, there are a number of outstanding regulatory issues, two of the most prominent being Basel III’s treatment of trade letters of credit, the most common instrument for financing trade, and the newly finalized output floor.

Trade letters of credit are off-balance sheet items, reflecting banks’ commitments. (Acknowledging the specific risk characteristics of trade letters of credit and recognizing the importance of this instrument for low income countries, the Basel Committee waived the so-called sovereign floor for trade finance instruments for banks using the SA. Under the sovereign floor, a risk-weight cannot be lower than the risk weight applicable to exposures to the sovereign of the country where the bank counterparty is incorporated.)

The Basel Committee believes the likelihood of trade letters of credit going from off-balance sheet items to on-balance sheet ones is higher than what the industry believes; hence, there is a disagreement on the appropriate risk weights. Banks argue that the default rates of trade letters of credit are the lowest among similar asset classes. But because of data limitations, they have been unable to directly address the Basel Committee’s concerns on the probability of trade letters of credit becoming on-balance sheet liabilities.

Global banks also caution about a potential adverse effect on trade finance arising from the newly introduced aggregate output floor in the finalized version of Basel III. This floor limits the use of banks’ internal ratings-based models (IRB) in the calculation of risk-weighted assets. Specifically, total RWA estimated by banks’ internal models cannot be lower than 72.5 percent of RWA as calculated using the standardized approach (SA). As mentioned above, global banks currently use their IRB models, rather than the SA to calculate capital requirements for trade finance. Thus, by being constrained in the usage of risk-sensitivity methodologies, global banks might face higher overall capital requirements derived from those activities, such as trade finance, where the standardized approach calls for more capital than what is needed under their internal models.

The discrepancies in views between the Basel Committee and the banking industry on the relative riskiness of trade finance products could discourage banks’ activities in this business line. When it comes to trade finance, overcoming data limitations will be key for regulators and global banks to see eye to eye. This task falls under the domain of the banks.

The next blog in this series will discuss regulatory asymmetries between domestic and foreign banks operating in emerging markets and development economies, stemming from the application of Basel III.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.