Some development fundamentalists think that aid should never be spent directly in the national interest. At the other extreme, some people—apparently including the UK Treasury—believe all development cooperation should be directly win-win.

Both these polar opposites are dangerously wrong: the truth is in-between.

This post identifies which types of development cooperation can be win-win, and which types of aid are seriously undermined by efforts to pursue the national interest—costing lives by reducing aid effectiveness. The more we tackle the underlying causes of poverty, the more opportunities there are for directly win-win policies. Good development policy should keep the distinction in mind.

The British Secretary of State for International Development, Penny Mordaunt, has said from the outset of her tenure that development cooperation can be “win-win.” In January she wrote:

Development policy will not exist in a vacuum. It will be part of a joined-up response to the challenges and opportunities we face as a country. This new offer will provide a clear ‘win-win’ for Britain and the world’s poorest.

The public have no truck with the polarized views of aid: The view we can only deliver a global goal in the recipient nation, that if we chose to it in a way that also brings other benefits, to the national interest, or another part of government, even if it is the most efficient, even if it is most sustainable way of doing it, that it is somehow less worthy. The public know that is perverse…To those who say you can’t spend ODA effectively and support the UK’s national interest, I say: ‘Watch us.’

There are three different senses in which our development cooperation can be win-win.

First, it is in our indirect long-term national interest for poor countries to become more prosperous, sustainable, and well-governed. The benefits to Britain include expanded trade and investment, and reductions in possible negative spill-overs of under-development such as infectious disease, environmental degradation, violence and human trafficking.

Second, our actions can contribute to global public goods and institutions which benefit both developing countries and Britain. Examples include cleaning up the sea, reducing climate change, increasing financial stability, developing new medicines, supporting the World Health Organisation’s capacity for disease surveillance, and improving the collection of taxes from multinational companies and international investors.

Third, our actions can benefit Britain directly. For example, opening our markets to developing country exports is good for developing countries and simultaneously good for British consumers (albeit not for some British producers who would face stiffer competition from abroad, but good for Britain as a whole). More contentiously, using aid to buy drugs from British pharmaceutical companies to give to the poorest people in the world benefits the British company and its employees as well as the families in developing countries who benefit from the medicine.

Most development campaigners are entirely comfortable with the first of these three types of win-win approaches to development and regularly cite our indirect long-term national interest as a reason to sustain the foreign aid budget.

Many people in development are also intellectually convinced of the second case, but worry that spending money on these global public goods will shift resources away from the very poorest countries and individuals. For example, we might pay Brazil to retain its tropical forests or work with China to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—that would be good for everyone, including Britain, but could result in less money being spent on the poorest countries that need it most.

Development campaigners are most sceptical of the third argument. They worry that aid will be spent far less effectively if it is also being skewed to the direct interests of the donors. This isn’t a merely theoretical concern. US food aid is theoretically “win-win” because the food has to be bought from American farmers and transported on American ships, but the result is that it feeds far fewer people than it could. The price of securing this “win” for the US is—literally—that more people die of starvation in developing countries than otherwise would. In the 1970s and 1980s, the UK wasted a lot of money on the Aid and Trade Provision (ATP) which sought to combine Britain’s development and commercial goals. So the quest for aid that supports the national interest as well as development sometimes imposes unacceptable compromises in the quality of aid.

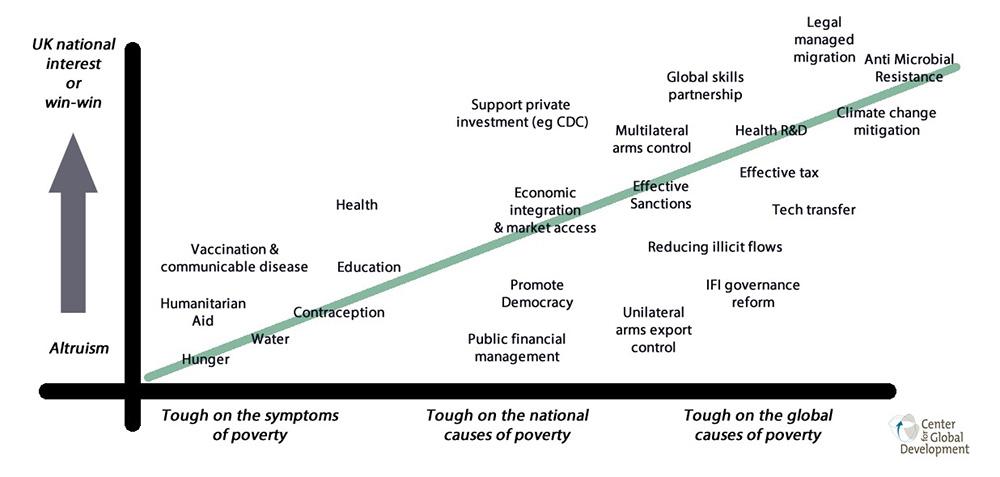

Here’s one way to approach this: the diagram below suggests that there might be a relationship between the amount of direct win-win in development cooperation and the extent to which a policy helps tackle the causes, rather than the symptoms, of poverty.

If our development cooperation is targeted mainly at the symptoms of poverty—such as by providing the poorest people with food and water—it is hard to see how that can be made more directly in the national interest without giving up a lot of aid effectiveness. This aid is still indirectly “win-win” in the sense that all poverty reduction and shared prosperity is good for Britain in the long run, but efforts to move these interventions from the bottom-left to the top-left of the chart, such as by tying humanitarian aid to UK producers, would be very damaging to the effectiveness of the aid.

But if we are aiming at reducing the causes of poverty—for example, by improving the effectiveness with which developing countries can collect taxes to pay for public services or by reducing the spread of antimicrobial resistance—then there are more opportunities for development cooperation which are directly win-win. This kind of development cooperation is often not mainly about spending aid money, but rather about wider government policies which directly benefit both the UK and developing countries.

Why is there this relationship? Actions to tackle the symptoms of poverty—down at the bottom left of the chart—are essentially about redistribution of resources (for example, by providing goods and services or through cash transfers). This should be done in whatever ways achieve the most value for money so that we can help the largest number of people. Because redistribution is inherently zero-sum, trying to do this in a way that also benefits the UK directly inevitably involves sacrificing development effectiveness. As we move toward the right on the graph, we are trying to expand the capacity of the planet to support the world’s population, doing more with less, accelerating innovation, and we are cooperating to solve global collective action problems. These goals are not inherently zero-sum, and so these approaches can be “win-win.” That’s why many of the types of development cooperation on the right hand side, which tackle the structural causes of poverty, can also be higher up the scale of being directly good for Britain too.

So if the Secretary of State is serious about making development cooperation win-win, then one way to achieve this is a greater focus on the policies and behaviours which address the underlying structural causes of poverty and on the global public goods and institutions which shape the context within which the poorest countries are developing. Aid spending on the symptoms of poverty can normally only be made directly win-win at significant cost to its effectiveness. Managing this aid altruistically benefits Britain indirectly, in the long run, through creating a more stable and more sustainable world.

These are not alternatives: the UK can, and does, both provide aid to meet immediate needs (such as humanitarian aid) and pursue a range of aid spending and other policies to address the causes of poverty (such as creating legal pathways for migration from developing countries). Arguably we do too little of the latter in development, partly because our development agencies are excessively focused on spending aid at the expense of other policies, and partly because tackling the symptoms of poverty yields quicker, more tangible, and more certain results. I hope that the quest for win-win development cooperation means we will in the future invest more in tackling the causes of poverty. If the Secretary of State is to make this a reality, she will need to engage other departments, not just to spend a greater proportion of UK Official Development Assistance but also to pursue genuinely win-win policies for Britain and the world.

Thanks to Maya Forstater for contributing key insights on an earlier draft.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.