This is a joint post with Sarah Dykstra.

CGD has just posted a policy paper by Sarah Dykstra and me on Millennium Development Goal 8 (that would be the one on a “global partnership for development”) and lessons for post-2015. It is an updated version of a paper we submitted to the High-Level Panel on post-2015 (available here) focused on what we thought should go into their Goal 12 (“Create a Global Enabling Environment and Catalyze Long-Term Finance”). It won’t take more than a cursory comparison of our paper and the HLP report to see we were less than completely persuasive!

One thing that we try to do is look at the impact of aid on progress towards the original MDGs. Given the MDGs’ origins in the DAC Development Goals, it is unsurprising that aid was considered the major tool by which rich countries would help poorer countries achieve the Millennium Goals. And a lot of the early work around how to reach MDG targets involved costing studies. The 2001 High-Level Panel on Financing for Development estimated that to reach the MDGs an additional $50 billion per year in ODA would be needed, for example.

As Andy Sumner and I reported a couple of years ago, a considerable proportion of the necessary aid suggested by MDG costing studies did flow to developing countries—OECD data suggests total net ODA from major donor countries increased from about $80 billion in the mid-1990s up to $127 billion in 2010. And that aid was increasingly focused to health and education as well as to sub-Saharan Africa (the region furthest behind). We also noted that progress in health and education had been slightly faster in the first decade of the new millennium than would have been predicted on the basis of historical flows.

In this paper, Sarah and I try to follow through the causal chain a little further—did countries that got more aid see faster progress in MDG areas? The short answer is: not much. Using Ben Leo’s measure of MDG progress, countries that are closer to reaching the goals have received less aid than those further behind. Using the Kenny-Sumner measure of progress compared to that which would be expected on the basis of historical trends, countries which received more ODA per capita did not see more rapid progress in the case of primary completion or gender equality in education. Countries that made more rapid than expected progress in child mortality did receive more cumulative aid from 2001 to 2010 than those countries that did not, although this result is not statistically significant.

That overall aid flows appear to be at best weakly associated with the rate of progress in MDG target areas does not mean that specific aid flows have not played a role. First, we are discussing more rapid progress than might be expected. Aid may have been important in sustaining historical rates of progress. Second, it might be that particular sectoral flows have played a major role—funding through the Education for All Initiative may have increased primary completion, for example, and health spending may have reduced maternal mortality. Not least, GAVI claims that since 2000 “370 million additional children have been immunized against leading vaccine-preventable diseases in the world's poorest countries with GAVI support.” And one piece of evidence that aid was nonfungibly used to increase vaccination rates is that GAVI-eligible low-income countries now have higher vaccination rates than lower-middle income countries.

In short, the evidence is (still) consistent with a story that suggests aid focused at particular MDG target areas can (and sometimes did) affect progress. But we should be cautious in our assumptions about how much aid can “bend the curve” of historical rates of progress in MDG outcomes, and concerned that aid appeared to be weakly targeted at the specific interventions likely to make the most difference to achieving the MDGs.

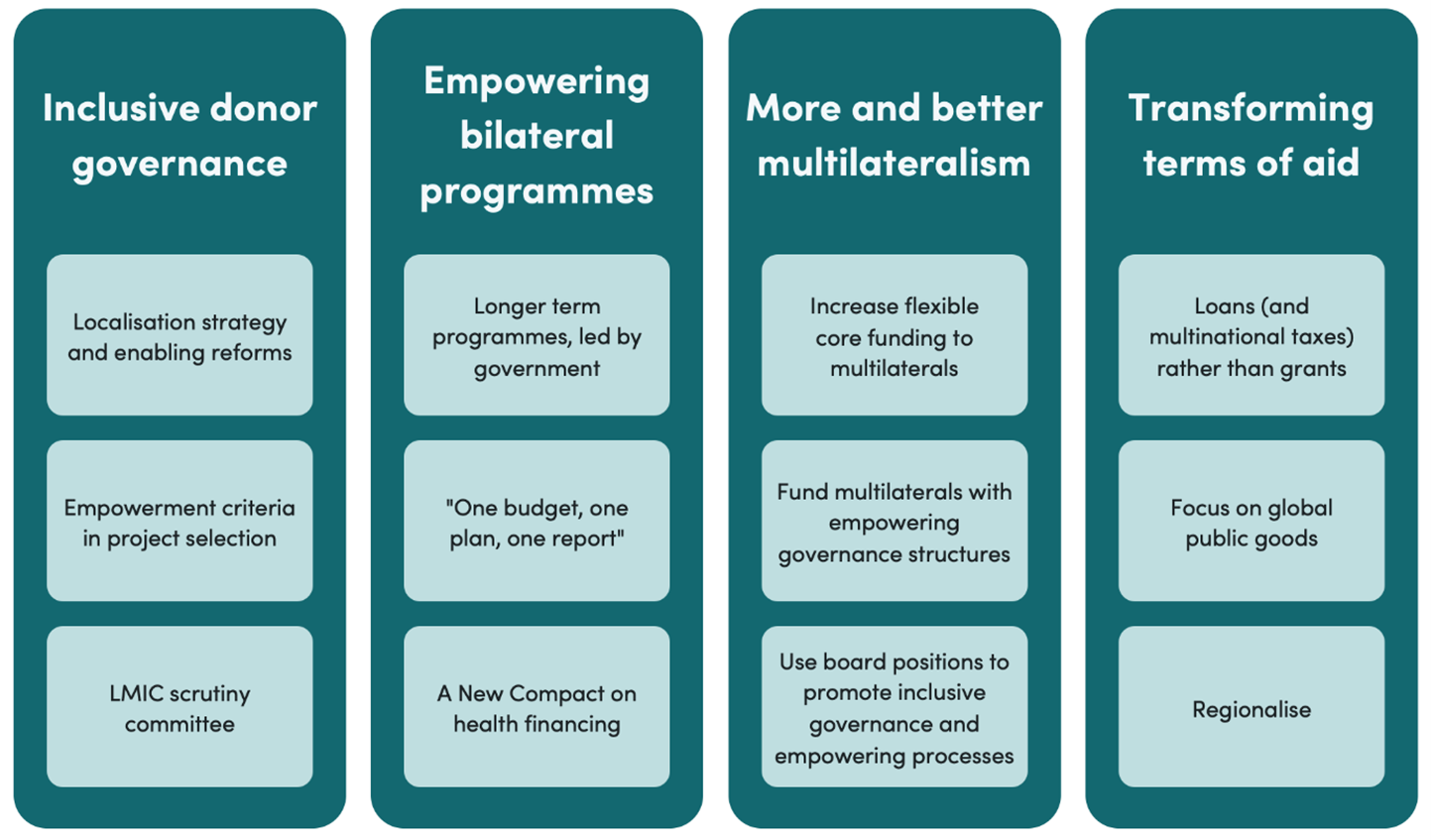

In turn, if aid is to play a role in forwarding the post-2015 development agenda, perhaps a tighter link between aid flows in general and post-2015 targets in particular should be established. One obvious tool to do that is Cash on Delivery Aid—donors could agree to pay the marginal costs of delivered progress on post-2015 targets. But the limited (if important) impact of aid also suggests that, with a set of goals that look to be even more ambitious than the original MDGs, we should be thinking about a much wider range of policy levers in rich countries to speed development progress in poor countries. The new MDG 8, or post-2015 Goal 12, needs stronger, better language not just on aid flows, but on trade, finance, tax, illicit flows, migration, intellectual property rights, research into global public goods, commitments to the global commons and global institutions … the list is long.

In that regard, our paper has lots of suggestions for post-2015 target language from the maybe plausible (“reduce the cost of remitting funds to low and lower middle income countries to below 5% of remittance value by 2020 and below 3% by 2030”) to the probably not (“we commit to an open, merit-based appointment system regardless of race, creed, sex or nationality throughout UN system at all levels”). No surprise that the High-Level Panel didn’t adopt many of those suggestions. But ambitious goals and a weak global partnership is no a recipe for post-2015 success, so let’s hope the demand for a strong MDG-8 successor as a vital element of the post-2015 agenda grows stronger.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.