Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric ID program, is at a crossroads. After a remarkable effort to enroll almost the entire Indian population of 1.25 billion in just over half a decade, its impact on privacy and distribution public benefits are being called into question. The concerns stem from the absence of a legal framework for collection and safeguarding of biometric information, as well as the policy framework that effectively makes Aadhaar authentication mandatory for accessing a variety of public services. In addition, there is disquiet with persistent efforts to persuade people to link bank, mobile, and tax accounts to Aadhaar in the face of uncertainty over the legal basis for this requirement. With the Supreme Court of India conducting hearings on a slew of petitions challenging its constitutional validity, it is fair to say that Aadhaar’s future and that of India’s digital governance reforms, hangs in the balance.

India’s Aadhaar debate is being closely watched across the world. Over a hundred countries—a majority of them in the developing world—have initiated programs that provide some form of digital identification for their constituents. Aadhaar’s approach is appealing to many countries. It collects minimal biographic data and avoids the problem of fragmented biometric databases and proprietary technologies that increase costs and reduce gains from digitization. Moreover, with the electronic Know Your Customer (e-KYC), Aadhaar has significantly expanded banking and financial services to the poor, streamlined government payments through direct transfers to beneficiaries, and enhanced the verification of existing and new mobile connections. These are important lessons that other countries are keen to learn from India’s experience.

Balancing development priorities and privacy concerns

The Aadhaar debate will therefore have an impact on the global discourse on how to balance the gains from better governance with individual’s right to privacy and protection of personal information in the digital age. ID programs are, of course, only one element of the general process of digitization that has been moving ahead rapidly across the world, including government, business, and social media. As recent events highlight, not all large data breaches involve centralized ID programs, and there also is no evidence that Aadhaar’s biometric database has been breached. Yet, by creating a common identifier, such programs do make it easier to integrate individual records across a variety of databases. The recent introduction of the “Virtual ID” is intended to mitigate this risk by providing users the ability to authenticate against a variable number; what remains to be seen is how widely it will be used.

Privacy aside, these are a number of distinct but often overlapping considerations that supporters and critics of Aadhaar need to weigh more carefully. The primary expressed motivation of Aadhaar has been to create an identity management and authentication system that would enable the government to improve the lives of the people. In rich countries as well as developing ones, poor people are frequently disadvantaged without having a trusted, recognized, and verifiable identity, especially in access to essential public services. Digital identity can increase state capacity to expand the beneficiary base for public goods and services while reducing the chances of corruption and “leakages” from inclusion of ghost and duplicate beneficiaries at the same time.

In considering the emerging lessons from India, one clarification to note is the difference between cleaning beneficiary rolls and changing the method of delivering benefits. On our recent visit we found very little discussion of what has been a relatively successful reform in the energy sector compared to other countries. Our recent paper on the reform of cooking gas subsidies in India (cited in the submission of the Attorney General of India to the Supreme Court on the constitutional validity of Aadhaar) explains how this this reform changed the mode of subsidy on cooking gas cylinders from in-kind to a direct transfer to the consumer’s bank account. This enabled the government to move from an administered price regime for domestic LPG to one where the consumers paid the market price and the subsidy was transferred directly upon delivery of the cylinder to the registered customer. The initial deduplication of LPG beneficiaries was undertaken with algorithmic matching of names and addresses that resulted in the issuance of a unique LPG ID number and this was only later tagged with Aadhaar and linked to bank accounts for the seamless transfer of the cash subsidy to consumers.

However, there is a continuing benefit of Aadhaar from maintaining the beneficiary list clean. This is done when new connections are issued, as in the case of the Ujjwala program that has provided new LPG connections to nearly 30 million poor rural women within the last two years. In the current scenario of increasing volatility in global energy prices, the gains from this reform could be substantial.

Improving quality of service delivery through digitization

A second point is the distinction between service quality and potential exclusion. In a recent survey on the perception and experience of digital governance that we conducted in Rajasthan, nearly half of the respondents said that they preferred the new system of LPG subsidy transfer over the previous one, with very few asserting the opposite view. As expressed by respondents, this was mainly due to the perceived reduction in corruption and black-marketing of subsidized cylinders diverted by dealers. Similarly, responses by beneficiaries of food rations through the public distribution system (PDS) showed that more preferred the new Aadhaar-enabled system than the previous system, again because they felt that their rations could no longer be diverted by unscrupulous dealers. These cases suggest the potential of digital systems to improve service delivery.

However, most of the debate has been focused on claims that PDS dealers are denying food rations, a constitutionally mandated entitlement, in the case that Aadhaar authentication of the beneficiary fails at the point of sale. Indeed, the government’s own submission to the Supreme Court flagged a problem. The Unique ID Authority of India (UIDAI) which is the custodian of Aadhaar’s database, stated that biometric authentication failure rate for fingerprints (after three attempts) was nearly 12 percent in government programs compared to 5 percent in banks and 3 percent for telecom operators. Other reports, including our own survey, suggest a rate of between 2 and 4 percent after repeated attempts.

The government’s figure is therefore unacceptably high when it comes to disbursal of benefits especially to poor and remote communities most in need. More understanding is urgently needed of the reasons behind their figure. In addition, it increases the importance of having effective protocols to manage exceptions, such as mobile one-time password (OTP) or iris-scan or authentication by a local authority. In Andhra Pradesh, the village Revenue officer is allowed to authenticate a beneficiary if needed as a last resort—a human response to possible failure of technology. Authentication failures of the magnitude cited in the government’s submission should serve as a wake-up call to urgently address this issue. Moreover, there could be a policy review to determine the need for “gold-plated” authentication of beneficiaries every time they access a service. Sometimes, the one-time deduplication of beneficiaries using Aadhaar may be more than sufficient for better delivery of services. When it comes to Aadhaar authentication, the best should not become the enemy of the (still very) good.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

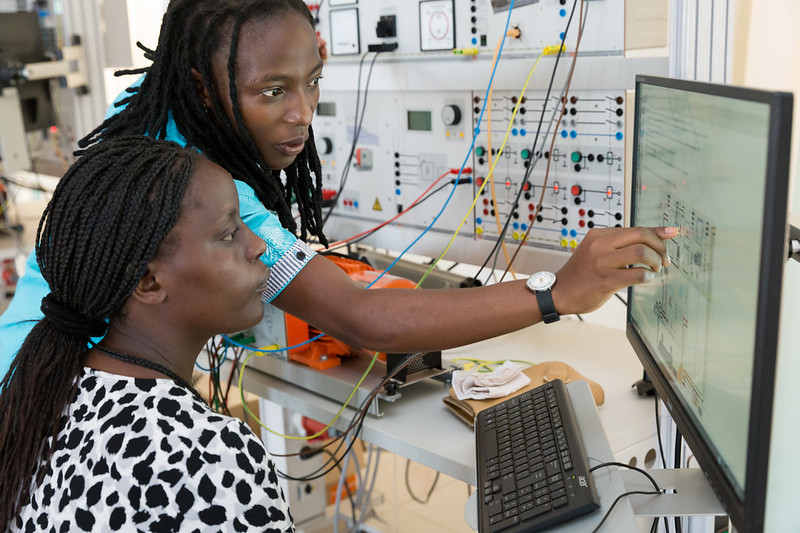

Image credit for social media/web: Social media image by Simone D McCourtie / World Bank